Life has not always been easy for Frances Arnold, the California Institute of Technology chemical engineering professor who shared in the Nobel Prize for Chemistry Wednesday. And it's not all about being a woman in a man's world.

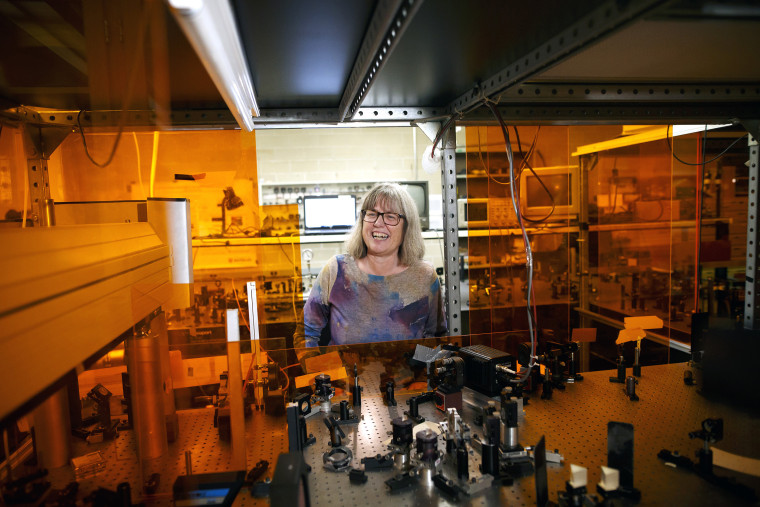

Arnold's win came as no surprise to anyone who knows her and her work. She is a heavy-hitter by any measure, well recognized for inventing a way to tweak evolution to manipulate enzymes.

But Arnold has also been forced to navigate a personal landscape of extreme adversity while forging her stellar career. Her first husband, biochemical engineer James Bailey, died of cancer in 2001.

Her former partner, Andrew Lange, was a prominent cosmologist who died by suicide in 2010.

Arnold was diagnosed with breast cancer in 2005. And in 2016 her son William Lange-Arnold died in an accident.

“So many things in my life have gone awry,” Arnold said in a speech she gave in 2017 at Caltech.

“Nine months ago my beloved son, William, died accidentally. He would have finished his junior year in college this week. His brothers and I experience a profound, ongoing loss, and every day I think of the wonderful man he was, and would have been.”

Yet Arnold managed and thrived as a single mom and a woman in a world heavily dominated by men. On Wednesday, she became only the fifth woman to win a Nobel Prize for Chemistry, and one of only 17 women to win one of the science-based Nobel Prizes, which include Physiology or Medicine, Chemistry and Physics. Since their start in 1901, Nobel Prizes have been awarded to 844 men and 49 women.

She predicted more women will eventually be recognized.

"There are lot of brilliant women in chemistry, a little later than some of the men, but they are amazing," Arnold told a news conference at Caltech Wednesday afternoon.

"We are going to see a steady stream, I predict, of Nobel prizes coming out of chemistry and given to women."

One of the other winners, Donna Strickland, shared the Nobel Prize in Physics on Tuesday. Her life story couldn’t be more different from Arnold’s.

Strickland, a physicist who specializes in laser technology at Canada’s University of Waterloo, keeps a low profile, is still an associate professor late in her career and didn’t even have a Wikipedia page until the prize was announced Tuesday.

Both women, however, are rare examples of recognition in two fields utterly dominated by men.

Strickland was surprised to learn that she was only the third woman to ever have received the Nobel Prize in Physics. The other two are Marie Curie, who won it in 1903, and Maria Goeppert-Mayer, who won in 1963 —55 years ago.

“Is that all, really? I thought there might have been more,” Strickland said at a news conference Tuesday.

Strickland’s work has led to the development of the pulsed lasers that are used, among other things, for the laser surgery that has restored clear vision to millions of people.

Arnold’s work has spawned multiple patents and companies. She has won numerous prizes, helped found biofuel company Gevo and sits on the corporate board of gene sequencing company Illumina Inc.

“If they had a special Nobel laureate for Nobel laureates, she’d be that person,” said Carolyn Bertozzi, a chemistry professor at Stanford University who calls Arnold both a friend and a colleague.

“Frances is an extremely strong, impressive singularity of a person.”

Arnold pioneered a new approach that used random genetic mutations to create custom enzymes, which are the biological compounds that power chemical reactions in living organisms.

“What Frances figured out how to do was to take enzymes that exist in nature and then evolve them to catalyze new reactions that never have happened on their own. Because of them, we can now make new molecules,” Bertozzi said.

“She figured out how to drive evolution in a test tube. She’s like her own Mother Nature.”

While doing this work, Arnold has acted as a mentor to younger men and women.

“She figured out how to drive evolution in a test tube. She’s like her own Mother Nature.”

She was the first female engineering professor that Hadley Sikes, now an associate professor in chemical engineering at MIT, had ever seen.

“I hadn’t had any examples of what a woman professor looked like. In my graduate Ph.D department there weren’t any women faculty members,” said Sikes, who earned her degree at Stanford University.

This lack of female supervisors helps explain the dearth of women in science, technology, engineering and mathematics in general, Sikes and others said.

There are fewer and fewer excuses for this, said Bertozzi. “The problem isn’t that girls are not interested in science. They are,” she said.

For decades, it was argued that women simply had not made the same achievements that men had. But what about Rosalind Franklin, the specialist in x-ray crystallography who helped discover the double helix structure of DNA? The Nobel prize for that discovery went to her three male collaborators: James Watson, Francis Crick and Maurice Wilkins, in 1962. Franklin had died in 1958 and Nobels are not awarded to people who have died.

And earlier this year, Jocelyn Bell Burnell of Britain’s Oxford University won public recognition with the $3 million Special Breakthrough Prize in Fundamental Physics. Burnell discovered a type of star called a pulsar in 1967 as a graduate student but her male supervisor won the Nobel for the discovery in 1974.

“I think the problem is that the older you get, the more, for women at least, you start to see the world as it is,” Bertozzi said. “That’s the turnoff. It’s when they’re older that the headwinds start increasing.”

Arnold did not let this happen to her.

“I think about all the challenges that Frances has faced and overcome, and in the face of those challenges she didn’t doubt her own worth or the worth of the projects she was working on,” said Sikes.

“She’s always followed her own path.”

Arnold, the daughter of a prominent nuclear physicist living in the Pittsburgh suburbs, hitchhiked to Washington, D.C. to protest against the Vietnam War in the 1970s and moved into her own apartment while still in high school, according to several media reports. She worked as a cocktail waitress and a cab driver, according to a profile in the Los Angeles Times.

"I've been called pushy and aggressive and all the negative words that are rarely applied to men with the same traits. But it doesn't bother me,” she said.

Arnold uses evolution in her work and says it is her inspiration, as well.

“To survive and even thrive in a changing world, nature offers another great lesson: the survivors are those who at the least adapt to change, or even better learn to benefit from change and grow intellectually and personally. That means careful listening and constant learning,” she said in her 2017 speech at Caltech.

Even for those who don’t know Arnold personally, her career has been an inspiration.

“She does seem like the definition of resilience,” said Beth Linas, an epidemiology researcher at Virginia-based health technology company Vibrent Health.

Strickland, too, inspires. “This is the first woman to win a physics Nobel in my lifetime,” Linas said. “It’s about time.”

CORRECTION (Oct. 4, 2008, 3:15 p.m.): An earlier version of this article misidentified the university where Arnold is a professor. It is the California Institute of Technology, not the California University of Technology.