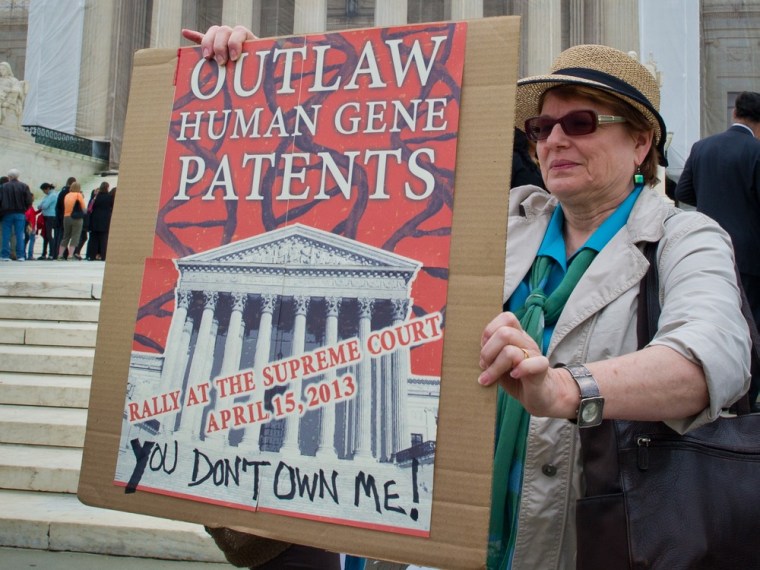

Can someone else patent your genes? The Supreme Court is scheduled to rule some time this month on that question – a suit filed against Myriad Genetics for its patent on the BRCA1 and BRCA2 gene mutations, which raise the risk of breast, ovarian and certain other cancers.

Opponents of patenting human DNA say a ruling in favor of Myriad will mean companies can own your genes, even though experts say it's more complicated than that. The patents set off a cascade of effects, opponents argue: it gives the company a monopoly on the test that can identify whether patients have the BRCA mutations so other companies can't offer their own tests as a second opinion. There's also no one to compete with the Myriad's $3,000 price tag on the test.

Myriad has long argued that it's not patenting anyone's genes. Instead, the company says, it separates them from the rest of the DNA and creates lab-made copies -- and that's what is patented and used in the test. The company has also licensed a few medical centers to run second-opinion tests.

But some say that regardless of how the court decides, it's likely the average person won't really be affected in any obvious, immediate way. Myriad's first 20-year patent on the genes runs out next year, although patent experts say the company has a variety of opportunities to extend that by a few years.

“Even if the patents are thrown out today, that doesn’t make the test available” since it would take time for other companies to develop a test, said John Conley, a law professor at the University of North Carolina who’s taken a special interest in the case. “The patents are going to expire before any competitors could come into the field anyway.

“This case would have been a lot more important had it been decided 10 or 12 years ago," he added. "A lot of things have happened in law and science since then."

The science has now moved far beyond the clunky, whole-gene sequencing method that Myriad uses so it's becoming less relevant. Companies can now sequence your entire genome for you, and in a few years they might even be able to interpret the information in a meaningful way.

Others are working from the opposite end – breaking the DNA sequences up into smaller, more digestible bits for analysis.

Myriad, the University of Utah and the U.S. government’s National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences filed an application for the first patent on the BRCA gene mutations in 1994. The Patent and Trademark Office granted the patent on BRCA1 mutations in 1997. Another patent, on BRCA2, was granted in 1998.

In the years since, it’s become clear that dozens and dozens of mutations affect a person’s breast cancer risk, and each patient has his or her own combination. But Myriad’s test remains a very important one, and its role was highlighted last month when actress Angelina Jolie said she’d had both breasts removed after finding out that her genetic inheritance gave her an 83 percent chance of developing breast cancer.

Myriad’s been strict in protecting its patents and access to the test for the most significant breast and ovarian cancer mutations. The Association for Molecular Pathology and American Civil Liberties Union led a batch of lawsuits asking that no one be allowed to patent human genes.

“Myriad has a patent on the BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes themselves. If Myriad had simply patented a test, then other scientists and laboratories could offer alternative testing on these genes,” the ACLU says on its website.

“But because it has patented the genes themselves, Myriad has the right to control all research and testing on or involving the BRCA genes.”

Myriad denies this. “No one can patent anyone’s genes. Genes consist of DNA that is naturally occurring in a person’s body and as products of nature are not patentable,” the company says on its website.

“In order to unravel the mysteries of what genes do, researchers have had to separate them from the rest of the DNA by producing man-made copies of only that portion of the gene that provides instructions for making proteins (only about 2 percent of the total DNA in your body). These man-made copies, called ‘isolated DNA,’ are unique chemical compositions not found in nature or the human body.”

The lawsuits say this is splitting hairs, since to do anything with human genes you first have to make copies of the DNA. “A disease-causing mutation means the same thing for the patient irrespective of whether a gene is examined inside or outside the patient’s body,” said Mary Williams, executive director of the Association for Molecular Pathology.

This is one of the decisions the Supreme Court is going to have to make.

In oral arguments in April, Supreme Court Justice Sandra Sotomayor asked if DNA was akin to the flour, sugar and other ingredients used in baking. Gregory Castanias, Myriad’s lawyer, said an analogy to a baseball bat was more like it. “A baseball bat doesn’t exist until it’s isolated from a tree,” he said. “But that’s still the product of human invention to decide where to begin the bat and where to end the bat.”

According to the ACLU, the patent office has granted patents on thousands of genes – adding up to 20 percent of all identified human genes. “A gene patent holder has the right to prevent anyone from studying, testing or even looking at a gene. As a result, scientific research and genetic testing has been delayed, limited or even shut down due to concerns about gene patents,” it argues.

While a Supreme Court ruling against Myriad wouldn't automatically affect the other patents, says ACLU lead attorney Sandra Park, other companies would be unlikely to try to enforce theirs any longer. "If they do seek to enforce, then that patent could be challenged in court citing to the ruling against Myriad," she said.

A ruling against Myriad would make genetic testing cheaper and more available, says Dr. Harry Ostrer, director of the Molecular Pathology Laboratory at Montefiore Medical Center in New York, and one of the individuals involved in the suit.

“It’ll give people more choices with regard to genetic testing,” he told NBC News. “It won’t be a question of Myriad’s way or no way. I think it’ll drive down the cost of genetic testing. It will help to contain the cost of health care and hopefully will increase the utilization of genetic testing.”

Most Americans who might get genetic tests are covered by health insurance. The tests have to be ordered by doctors, and people without health insurance are far less likely to see a doctor in the first place. Few people are paying for these tests out of pocket, and few would notice any effects from the ruling.

Science is already changing how doctors use patients' genetic information, in far more profound ways than a patent will affect.

That said, the ACLU says Myriad's enforcement of its patent rights have held up development of lifesaving cancer therapies that target a patient's specific genetic mutations - an experimental class of drugs called PARP inhibitors is an example. The Food and Drug Administration requires approval of the gene test that goes with the associated targeted therapy, and Myriad only sought that approval for the first time last month.

"Patents on the BRCA genes have stopped laboratories from providing testing that include analysis of those genes with other genes connected to breast and ovarian cancer risk. University of Washington wants to offer such testing to patients, but cannot, due to the patents," Park adds.

Ostrer says his lab is working on a comprehensive, one-step test for people wanting to know their full genetic breast cancer risk.

“We would like to develop a genetic analysis where we sequence not only BRCA1 and BRCA2 but all other genes that raise the risk of breast cancer,” Ostrer says.

Robert Cook-Deegan, a public-policy professor at Duke University’s Institute for Genome Sciences and Policy, says that’s where the market is headed, anyway. “The writing on the wall is quite clear. It makes no sense right now to be testing for just two genes,” he said.

Only a small percentage of the population needs to worry about the BRCA genes, Cook-Deegan noted. “It’s somewhere, at the most, 5 percent to 10 percent of people who get those cancers because of inherited risk,” he said.

And Cook-Deegan says other court rulings have made it clear that previous patents on genetic material were too broad. “I think it does matter what court says and how broadly it says it,” Cook-Deegan said. It will affect not patients, but business decisions about getting into the genetic testing market, he predicted.

Conley says Myriad’s made it clear that it’s moving beyond the idea of holding and guarding a patent and gene test as a business model.

“Myriad executives have made public comments about new business enterprises in Europe that are going to rely on databases, not patents,” Conley said. “There aren’t many companies that are situated just like Myriad is now, with a large business based on one or a couple of single gene patents. It’s pretty unique.”

Twenty years of exclusive rights to genetic testing have given the company a lot of data. “They built up a huge database correlating gene mutations with health effects,” Conley noted.

For now, all sides have to sit tight. The Supreme Court is due to issue its ruling before it goes on summer recess at the end of the month, and for now, rulings are scheduled to come on Mondays, and possibly on Thursday, June 13. The Court’s been known to add days to its schedule, though – last year’s ruling on the constitutionality of the 2010 health reform law came on the last possible day.

Either way, the decision may call for a drink, says Ostrer. “I am planning to go drinking with my buddies from the ACLU once the ruling comes down,” he said.

Related: