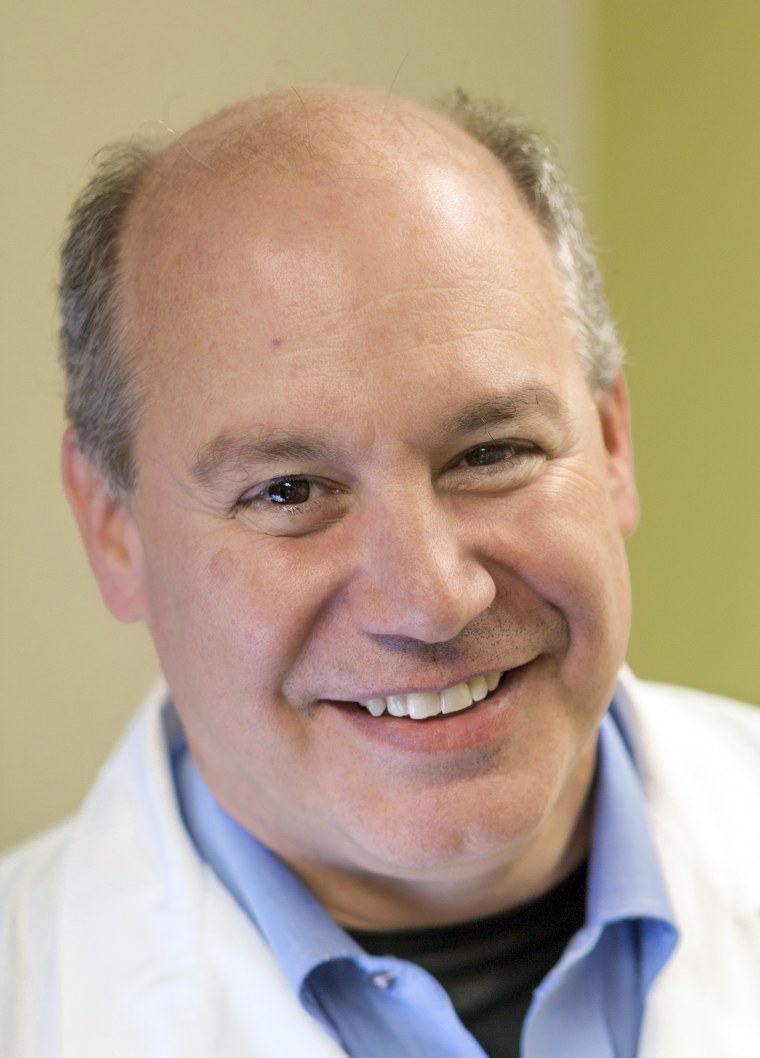

Dr. Michael Saag is one of the nation's best authorities on the coronavirus — not only because he's researched viruses for more than three decades, but also because he recently recovered from the illness himself.

Saag has published research on HIV/AIDS dating back to the 1980s. He now serves as the associate dean for global health at the University of Alabama at Birmingham, as well as the director of UAB's Center for AIDS Research.

Full coverage of the coronavirus outbreak

He was diagnosed with COVID-19 just over one month ago, on March 16. He described the illness as a "horror" that included fever, muscle aches, fatigue and difficulty thinking.

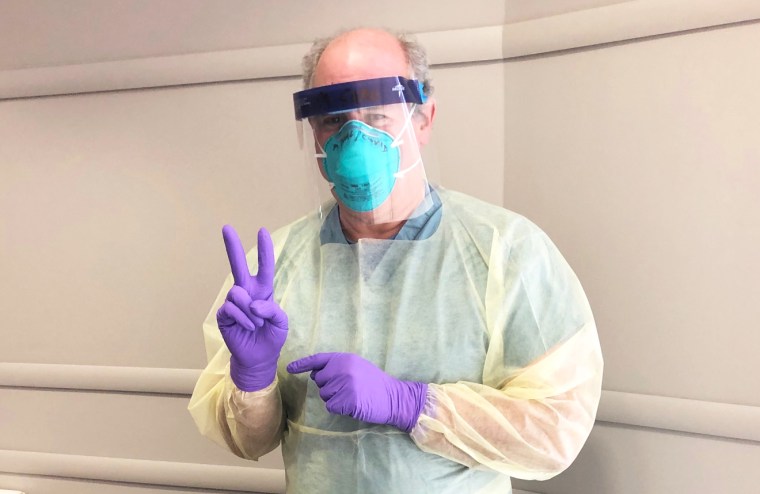

Now fully recovered, Saag, an infectious diseases doctor, treats other COVID-19 patients at a clinic in Birmingham.

NBC News spoke with Saag recently about his experience with the illness, which he recovered from without needing to be hospitalized. The conversation has been lightly edited for length and clarity.

NBC News: Talk about your personal experience with COVID-19. How did the illness affect you?

Saag: It's been an interesting ride; a scary roller coaster, and every night is horrible. The mornings are better, but it sort of teases folks — myself included — into thinking that it's going away. And then, boom,! It comes right back. For me, that went on for eight days in a row.

I would sit awake, counting the minutes until morning almost, wondering if my breathing was going to get worse and I'd end up on a ventilator.

The nights are so bad, because as a physician, I know what can happen. And so I would sit awake, counting the minutes until morning almost, wondering if my breathing was going to get worse and I'd end up on a ventilator. That was the horror of it.

NBC News: What was your treatment plan?

Saag: We don't have a proven treatment and I think that's essential to understand. It points out how spoiled we've become in the world of medicine. We have so many treatments for so many disorders that we just assume that when something pops up, we can handle this.

But the reason we can handle it for other diseases is that we've had time to do randomized trials that we haven't had time to do with COVID. So, in my case, after the second night of horror I'll call it, I was very concerned that I was heading the wrong direction. And that's about the time a study came out that suggested using hydroxychloroquine with azithromycin.

So I called 10 colleague experts and said, 'What do you think?' They said, 'Well, go ahead and try it.' I did. I can't really tell you it helped or hurt. In retrospect, now that I've been able to look into it a little bit more, I'm a little bit ashamed of myself, because I could have put myself into harm's way in terms of sudden death. That can happen when you use those two particular drugs together, because they can cause a fatal arrhythmia, and I was not being monitored properly.

The take-home point is I totally get why someone who's that sick would want something, because doing nothing is very, very difficult.

On the other hand, we really do need randomized controlled trials to tell us the truth of what the drug regimen does or does not do, and what its safety profile is. Until we have that, we're really trying to fly an airplane in fog without instruments.

NBC News: You've not only been infected yourself, you're treating patients at a COVID clinic. What more are you learning about the symptoms and how this disease is acting in people?

Saag: It's unique. The infection is not like the flu that hits you all at once. These symptoms sort of gradually creep up on folks, and then it crescendos.

For some people, they may not have symptoms at all or they could clear it in five days. But for most people, by five to 10 days, that's when symptoms intensify, and are typically worse at night: fever, muscle aches, fatigue, headache.

Loss of sense of smell is kind of a unique symptom. It's not present in everyone. But if I have a patient call me and say, 'I don't feel good and I've lost my sense of smell' — until proven otherwise, they have COVID, there's no question about it.

Download the NBC News app for full coverage of the coronavirus outbreak

NBC News: It's now been shown the virus can have a neurologic impact. Did you have those kinds of symptoms?

Saag: There's no question that it clouds cognition. At night, I was not thinking clearly. I can't say I was delirious, but I had to focus hard when talking. And I had to focus hard when thinking of, for example, answering an email, which I learned not to do when I didn't feel well.

NBC News: What mechanism do you think causes those cognitive deficits?

Saag: I'm pretty confident it's inflammation. It's our immune system that's aggressively attacking the virus, and the byproduct of that battle is causing collateral damage. It's friendly fire. It's our immune system going haywire trying to throw everything at this virus. But in the course of doing that, it's causing damage inadvertently to other tissues.

To get a little bit more technical, when the immune system responds to a pathogen, say this virus, [the immune system] recognizes that it's under attack. And it fights by recruiting other cells of the immune system and it does that by releasing chemicals called cytokines.

These cytokines can be released in prodigious amounts. And when they are released, that's what causes the symptoms of the infection. And the cytokines are released into the body. And those are the things that in my opinion, are causing the other symptoms such as cognitive dysfunction, neurologic sequela, heart trouble, kidney failure, maybe even the diarrhea that we see.

And it's not until those cytokines come back under control, that the body starts to heal.

NBC News: What do we know about immunity and how long might that last?

Saag: Well, I am connected to a lot of people in research labs, so I sent blood off to several places. I've been informed that I have high levels of antibody, and those antibodies seem to be neutralizing antibodies, which means that they can attack the virus, and protect cells and tissue culture from becoming infected.

But the question still remains: how does that translate into true protection should I be re-exposed to the virus?

Based on other viruses that we encounter, like measles or mumps, the evidence is pretty clear that that type of immunity is protective. But in other infections, such as hepatitis C, people can be reinfected. The same thing is true for viruses like dengue, which is a tropical virus.

So it's not 100 percent clear with coronavirus, but my personal bet is that the immunity will be protective.

If that's true, then that's great news because the people who've had the infection are protected, and that's going to help us get out of this in the long run. But more importantly, it means that a vaccine can work.

A vaccine will be a game changer. That will allow us to think about getting back to "normal life" if it's available — widely available — and effective.