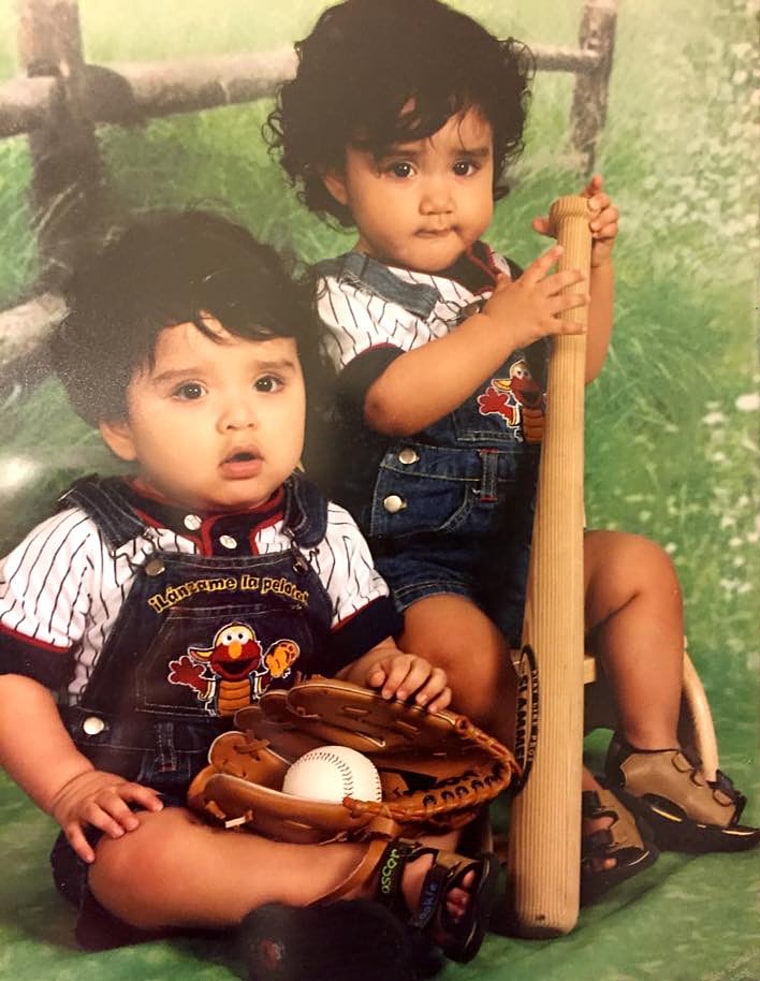

When Lizzie Acevedo’s fraternal twin sons, now 15, were newly diagnosed with autism, she was hopeful about diets and vitamin injections that were being touted as miracle treatments or even cures.

Around age 4, the boys were on a gluten-free, casein-free diet, and for a couple months they mainly ate a special organic brand of chicken nuggets. Wheat products or anything else with gluten were out, as were dairy foods containing the milk protein casein. Acevedo also started giving vitamin B12 injections, prescribed by a Defeat Autism Now! doctor, to her son Omar, who is nonverbal and has more significant intellectual disabilities than his brother, Jorge, who speaks and is more independent.

“Back then, I just needed something to make things better,” Acevedo said. She tried the treatments for a few months but stopped when she didn’t see a noticeable effect.

Now, a decade later, Acevedo has heard about lots of hyped alternative approaches for autism, most recently worrisome reports of parents giving their kids bleach drinks or enemas. However, she’s also learned there aren’t any quick remedies for autism, which affects brain development and is characterized by difficulties with communication and social skills and by restricted interests and repetitive behaviors.

“There’s no cure for autism and anybody who tries to sell you a cure is lying,” Acevedo, a single parent and a fifth grade teacher in Los Angeles, said.

But she understands why parents of autistic children can fall prey to scams. “I’ve been where they are now, and I know how desperate it feels to want to get your child to be better,” she said.

'More complicated than anyone ever thought'

When autism research started to really accelerate a couple decades ago, many scientists thought finding a cure might be easier. Today, the latest science points away from a single cure, but there are ways to help autistic people lead healthier, happier lives and more that can be done to help.

“I think that given the complexity and the variability of the causes and the manifestations of autism, trying to come up with a cure is probably not the right approach,” said autism researcher and psychologist Len Abbeduto, director of the University of California, Davis, MIND Institute in Sacramento.

An estimated 80 percent of autism cases involve genetic factors, and it tends to run in families, but there is no single “autism gene,” Abbeduto explained. In fact, research has shown that more than 100 genes, and maybe upwards of 1,000, may play a role. Researchers also suspect that environmental factors — such as exposures to infectious agents, pesticides or other toxins in pregnancy — may play a role.

“Scientists are investing a lot of work into understanding the genes but we’re also realizing it’s a lot more complicated than anybody ever thought when they started out,” psychologist Ann Wagner, national autism coordinator for the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, said.

It’s highly likely that there are different causes for different kinds of ASD.

“We do know that it’s highly genetic, we just haven’t identified how particular kinds of genes might interact with each other or with other factors to cause autism spectrum disorder,” Wagner said. “Autism is such a heterogenous disorder, so it’s highly likely that there are different causes for different kinds of ASD.”

These research developments come amid growing controversy over whether autism even needs a cure. Autism Speaks, an advocacy and research group founded in 2005, removed the word “cure” from its mission statement in 2016.

“In the beginning, [researchers] were looking more for the magic bullet, the magic pill. We were looking for the autism gene, and we thought that would ultimately lead to some kind of cure of autism,” psychologist Thomas Frazier, chief science officer at Autism Speaks in New York, said. “Then we recognized that we were way off base.”

Focusing on early diagnosis

Now, researchers have turned much of their attention to identifying autism in children as early as possible in hopes of intervening sooner with therapies to try to alter the developmental trajectory of their young brains. While skilled practitioners can diagnose autism in toddlers at 18 to 24 months of age — with some research indicating there are detectable signs in babies as young as 6 months — most kids aren’t diagnosed until age 4.

Katarzyna Chawarska, a professor of child psychiatry who leads Yale University’s Autism Center of Excellence in New Haven, Connecticut, is studying signs of autism in babies. “The reason why we are focusing so much on early diagnosis is that it is our hope that by intervening early, we can capitalize on still tremendous brain plasticity that is present in the first, second, third year of life,” she said.

The goal, Chawarska said, is “to help alleviate the symptoms and make sure that every child with autism reaches their full potential.”

If you’re trying to get rid of autism, you’re trying to get rid of us.

Doctors, for instance, would like to minimize any intellectual disabilities and help patients communicate better and improve socials skills. They also want to quickly identify and address any medical conditions that often accompany autism, such as seizures, gastrointestinal problems, sleep disorders, Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder and anxiety.

Researchers already are seeing positive results with interventions such as behavioral treatments and speech therapy in toddlers.

“One of the things that we do know is that intensive early intervention improves outcomes for kids, so the earlier we can intervene the better,” Abbeduto said.

The idea of curing autism also has become highly controversial with the growth of the neurodiversity movement, which emphasizes respecting and valuing all people for who they are, regardless of whether they are “neurotypical.”

“The ‘C word’ raises a lot of attention in the community at large,” said Michael Maloney, executive director of the Organization for Autism Research, a group in Arlington, Virginia, that funds research to improve the daily lives of autistic people. “The largest objection is from people with autism who see themselves as independent and competent and don’t see themselves as broken and needing to be fixed.”

Among the critics is Julia Bascom, executive director of the Autistic Self Advocacy Network, a Washington, D.C.-based group that is run by autistic people, including herself.

“Self-advocates have been largely successful at saying this concept of a cure is really offensive,” she said. “Who we are is OK, we just need support.”

Bascom isn’t opposed to research and therapies that help autistic people — as long as they aren’t trying to strip them of their autistic traits.

“If you’re trying to get rid of autism, you’re trying to get rid of us, and that’s something our community takes really personally,” she said. “There are certainly a lot of co-occurring conditions like epilepsy that a lot of us have that we’d like to not have. But we don’t tend to feel that way about autism and we get really concerned when we see all this money going into risk factors and causation and genetics as opposed to finding out why autistic people tend to have shorter lifespans, or why our suicide rate is nine times higher than average, or what autism really looks like in adults.”

Some of her other questions include why girls and people of color are diagnosed later in life, why autism has so many co-occurring conditions, why people with autism tend to react differently to medications, and why they engage in self-injurious behaviors, such as head banging and skin scratching.

Falling off the 'services cliff'

Like Acevedo’s boys, a growing number of teens and adults are living on the autism spectrum, but Bascom and others say there is far too little research on understanding how autistic people are affected across their lifespan and how to help them live life to the fullest. Most autism research dollars in the United States go toward understanding the biological underpinnings of autism in order to diagnose and treat young children.

Autism research spending in the U.S. totaled more than $364.4 million in 2016, the latest year for which figures are available, with 80 percent of that money coming from federal agencies and 20 percent from private organizations. Of the spending, just 2 percent went toward autism lifespan issues and 5 percent toward services, according to the government’s Interagency Autism Coordinating Committee. An additional 35 percent went to biology, 24 percent to risk factors, 16 percent to treatment and interventions, 10 percent to infrastructure and surveillance, and 8 percent to screening and diagnosis.

Paul Shattuck, director of the Life Course Outcomes Research Program at the A.J. Drexel Autism Institute in Philadelphia, and a member of the scientific council of the Organization for Autism Research, agrees that not enough attention is paid to adults with autism.

“We’re expending a lot of effort for very young children with autism, but as a society we kind of drop the ball once these young people become young adults,” he said. “There’s really not much there for autistic adults or their families in terms of services or even thinking how to support autistic people across the lifespan.”

There aren’t exact figures on the total number of Americans with autism but by one estimation 3.5 million people are on the spectrum, and diagnoses have been increasing. About 1 in 59 children are on the autism spectrum, according to the latest Centers for Disease Control and Prevention figures from 2014, up from 1 in 150 kids in 2000. While some of the increased prevalence may be a true increase in autism cases, the CDC says that a broader definition of the autism spectrum and improved diagnosis efforts likely contributed to the higher numbers.

By Shattuck’s latest research estimates, 70,000 to 80,000 or more autistic youths per year will turn 18. “That’s close to a million people over the next decade,” he said, highlighting an urgent need for research to address the health and well-being of autistic adults.

Autistic kids are eligible for special education services while they are in school, and services can last until age 21, but help is harder to come by after that. “When teens exit high school, they fall off what is called the services cliff,” Shattuck said. “It becomes much more difficult to find help and services once kids age out of eligibility for special education. And the young adult outcomes and the adult outcomes are pretty dismal frankly.”

After high school, most young autistic adults do not have jobs, career training or additional educational opportunities. Autistic adults also struggle to find independent living arrangements, maintain friendships, get involved with community activities or have enough money to pay for their needs, said Shattuck, whose center helps autistic people and their families with paperwork for Medicaid, Social Security, group housing and more. Many autistic adults continue to live with their parents, raising concerns about what happens when the parents pass away.

Wagner, the national autism coordinator, agrees there needs to be more research on autism across the lifespan and said the government is trying to attract and fund more research in this area.

Just like parents everywhere, Acevedo wants the best for her kids. But after Omar and Jorge finish high school and special education services end, she wonders — and worries — about what the future holds.

“I would love to see some more money put into the transition of young adults with autism into the most independent living situation they can get,” Acevedo said. “I would love to see money put into job training, taking the skills that these children have — because everybody has skills, something that they can do — and just really refining it and making these kids marketable to where they can earn some sort of income. There’s something about getting a paycheck and having your name on it as an adult that means so much, and I’m sure it’s going to mean a lot to my kids.”

Shattuck says helping autistic adults or those with disabilities ultimately helps everyone.

“Our organizations and our communities function better when we make space for everyone of all abilities,” he said. “It’s about helping ourselves and helping our communities be better, higher quality places for all of us.”

Follow NBC HEALTH on Twitter & Facebook.