Since 1924, more than 100 million cases of childhood disease in the U.S. have been prevented through vaccination programs. Yet new findings show that when an epidemic is in full swing, and serious illness could be averted, immunization rates do not increase.

Researchers compared rates of infant immunization during an outbreak of whooping cough, also called pertussis, in the state of Washington in 2012.

Despite efforts by public health officials encouraging vaccination, the researchers found no difference in vaccination rates before and during the epidemic among the 80,311 total infants included in the study, to be presented Monday at the Pediatric Academic Societies annual meeting in Vancouver, B.C.

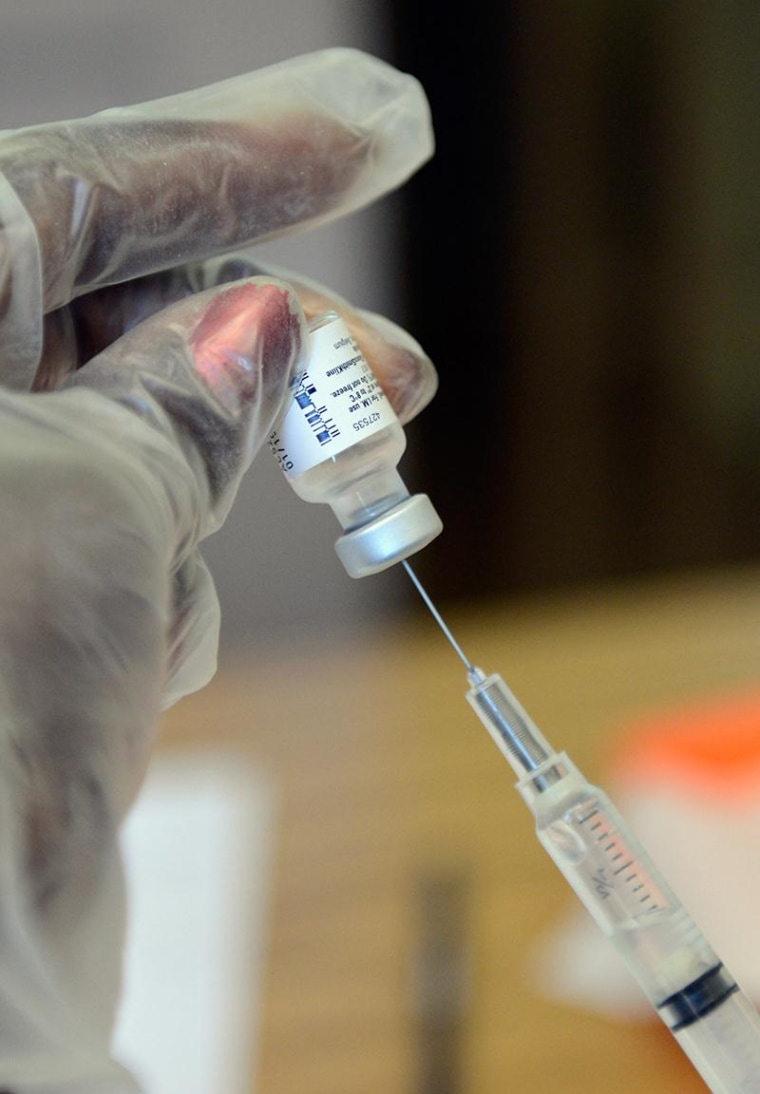

Pertussis, which takes a hard toll on infants, is a highly contagious disease, marked by uncontrollable, often violent coughing. Immunization is achieved with a combination shot called DtaP, which protects against diphtheria, tetanus and pertussis. The vaccine is given in several doses, with the first dose at two months of age.

The percentage of infants who were up-to-date with a pertussis-containing vaccine was 67.4 percent pre-outbreak, and during the outbreak 69.5% of infants were immunized, a 2.1 percent difference, which is “not statistically significant,” explains lead researcher Dr. Elizabeth R. Wolf, the Ruth L. Kirschstein National Research Service Award Fellow in General Academic Pediatrics at University of Washington, Seattle Children’s Research Institute.

“Vaccination rates in the U.S. are still below public health goals (and) we don’t fully understand what improves vaccine acceptance,” she says, although conventional wisdom would state when the when the risk of disease is high, acceptance of a vaccine should increase, especially if that vaccine has proven effective.

Doctors aren’t sure why the vaccination rate did not increase, although they have their suspicions.

“One possible explanation is that parents’ fear of adverse events still outweighed the fear of disease even in the face of an epidemic,” Wolf says. And although DTaP is a well-established vaccine with very few side effects, “it is possible that parents may have generalized concerns about vaccine safety.”