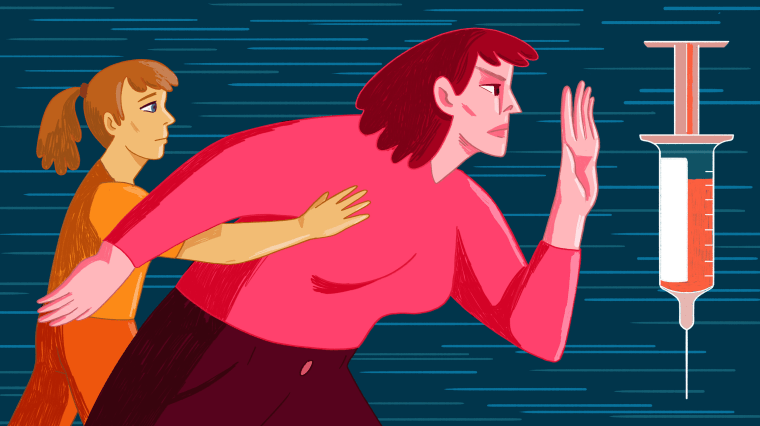

Jennifer Canada remembers when her pediatrician in Middletown, Maryland, recommended a vaccine that would protect her against a virus that is known to cause several types of cancer. But Canada’s mother, who had consented to all of the other recommended immunizations for her 13-year-old daughter, declined it, saying she'd heard rumors that the shots had caused the death of several girls.

The doctor didn’t push the issue, and neither did the young teen.

“Until college, I believed, like so many others, that the vaccine was not safe, and that it was far more suited to teens with risky behaviors,” Canada said.

It wasn’t until after beginning a career in cancer research that Canada realized how lucky she's been to avoid exposure to human papillomavirus, the most common sexually transmitted infection in the U.S. Now 26, she just finished the three-shot HPV vaccine series recommended for adults by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

But even if Canada had wanted the HPV vaccine during that doctor visit, Maryland has no statute or regulation that allows dependent teens to be vaccinated without their parents’ consent. Neither do at least 23 other states. Generally, unless teens are legally emancipated, married or are already parents, they have no recourse when their parents or other legal guardians refuse vaccines, including the HPV shot, on their behalf.

However, in the wake of an increasingly visible anti-vaccination movement, concern over the measles outbreaks in the U.S., more state legislatures are trying to create a legal way for dependent teens to get vaccinated, in particular the HPV shot, without their parents' consent.

This year, lawmakers in the New York state Assembly and Senate attempted — but failed — to pass bills allowing teens to consent on their own behalf to being vaccinated for HPV and Hepatitis B, both sexually transmitted infections.

Similar bills have been proposed in New York every year since 2009 and stopped short every time, in part because Republicans controlled the state Senate until 2018, said Assemblywoman Amy Paulin, a Democrat who put forth the Assembly version of this bill.

“Anything related to children having sex tends to be a detriment for legislation,” Paulin said.

This repeated stall may explain why the New York state Department of Health decided to act independently. In 2017, they changed regulations to allow all teens in New York to get the HPV shot on their own. However, Paulin still plans to re-introduce her own bill to protect this right with the force of law.

“My concern is that if we don’t codify this, we may lose it at a future point,” she said.

Each state has legal exceptions that allow minors to get diagnosed and treated for sexually transmitted diseases. In addition to New York, California, Delaware and Washington, D.C., allow teens under 18 to be vaccinated for HPV and hepatitis B, which is also sexually transmitted. And as measles spread in New Jersey this year, a bill was introduced in May that would allow teens as young as 14 to be vaccinated against a number of diseases, including HPV, without parental permission.

The move to give teens a voice in vaccination comes on top of a growing body of evidence that the HPV vaccine, which protects against a range of deadly cancers, is far more effective in protecting against HPV-related diseases than expected.

At least 79 million Americans, mostly in their late teens and early 20s, are infected with HPV, according to the CDC. Every year, about 33,700 new cancers linked to HPV are diagnosed in the U.S., and more than 4,000 American women die from cervical cancer. Almost all cases of cervical cancer are caused by specific types of HPV, as well as 90 percent of anal cancer cases.

The vaccine is most effective if the child has never been exposed to those viruses, which is why the CDC recommends vaccinating children ages 9 to 12, before they become sexually active.

Since the introduction of the Gardasil shot in 2006, it has inflamed fears about injury and promiscuity among young teens. Only about 43 percent of teens, ages 13-17, in the U.S. have received all the recommended dosages of the HPV vaccine, according to the CDC.

Worry about side effects

Parents who decline the vaccines for their children tend to cite safety concerns and the belief that their child will not need it, according to a 2018 study by Johns Hopkins researchers.

Even parents who support other childhood vaccinations worry about HPV shots.

All of Stacy Clark’s six children, three girls and three boys ranging from 6 to 15, received the regular schedule of childhood immunizations. But as the kids are growing up, Clark and her husband have opted against the HPV vaccine because they don’t feel it is worth any potential risks.

“Other childhood vaccines protect against epidemics that basically have been wiped from our screen, and we don’t want to bring any of those diseases like measles back,” said Clark, a nurse in Glendale, California. “But with the HPV vaccine, and the flu vaccine, which my kids also do not get, I feel that if you take good care of your body and go to the doctor regularly, these conditions are not likely to kill you as long as you’re getting regular health care.”

Women, for instance, can get Pap smears to check for the sexually transmitted HPV, Clark said. “I feel like we would be able to catch a problem before it became severe,” she said.

And Clark worries about potential side effects. There have been rare cases of allergic reaction, or anaphylaxis, related to the HPV shot, according to the CDC.

“All of the standard vaccines for kids are tested, and tried and true, and in existence for a long time,” she said. “But HPV is newer. I don’t need my kids to be guinea pigs. I’d rather err on the side of caution.”

But Kristen Nordlund, a spokeswoman for the CDC, counters that "over 10 years of monitoring and research have shown that HPV vaccination is very safe.”

“HPV vaccination provides safe, effective and long-lasting protection against cancers caused by HPV," Nordlund said.

While it's unclear if allowing teens to consent to HPV shots would increase vaccination rates in the U.S., barring them from confidential health care makes it more difficult for them to access sensitive health care services like STI treatment and reproductive care, said Robin Chappelle Golston, president and CEO of Planned Parenthood Empire State Acts, the New York advocacy arm of Planned Parenthood.

"Adolescents with confidentiality concerns are less likely to seek care related to reproductive and sexual health care than those without confidentiality concerns," Golston said.

All 50 states and Washington, D.C., have laws that allow teens still living at home to seek diagnosis and treatment for sensitive health care issues like sexually transmitted infections, mental health problems and substance use disorders without the consent, and sometimes without the knowledge, of their parents.

Eighteen states have laws or regulations that either explicitly allow teens to self-consent for all medical treatments or the HPV vaccine, or interpret existing statutes similarly. Meanwhile, 24 state health departments say that dependent teens cannot self-consent, although spokespersons from Utah and Michigan point out that teens who enter a Title X provider like Planned Parenthood can do so.

A handful of states have statutes or regulations that are open to interpretation or couldn’t be clarified by the state's department of health.

Would new laws empower teens or split families?

Advocates say that the right to be vaccinated against a sexually transmitted infection makes sense in light of public health laws allowing teens to get diagnosis and treatment for STIs without parental consent. However, states need to make this right explicit with new laws that specifically name vaccines or immunizations, and lower the age of consent for vaccines to 12 or 14, said Ross Silverman, professor of health policy and management at Indiana University's Richard M. Fairbanks School of Public Health.

And in order to make these new laws most effective, teens need better information about how the vaccine can protect them, said Fred Wyand, a spokesman for the American Sexual Health Association and the National Cervical Cancer Coalition.

“We don’t just give kids driver’s licenses when they turn 16 and say ‘OK, have at it!’” Wyand said. “We have to teach them the rules of the road, how to safely operate their vehicle, how to change a tire and so forth. That approach works with health topics, too.”

However, Dr. Cora Breuner of Seattle Children's Hospital and chair of the American Academy of Pediatrics' committee on adolescence, cautions that creating a rift that divides families is not the goal.

The AAP doesn’t have a formal position on new bills that allow teens to get the HPV vaccine on their own, but acknowledges that parents should generally be recognized as the best people to make medical decisions for children and teens.

Breuner prefers to create a dialogue with parents about the need for vaccines.

“As a pediatrician, my complete moral compass, is that the family has the right to determine the medical welfare of their children,” she said. “Education, persuasion, gentle and compassionate understanding of other opinions is the way to go.”

Follow NBC HEALTH on Twitter & Facebook.