At 20 weeks pregnant, Marlise Munoz is on life support in an intensive care unit in Fort Worth, Texas. She is also, according to her family, dead.

Marlise Munoz’s husband filed suit Tuesday to force the hospital to remove the 33-year-old brain-dead woman from life support. The court should honor his request and reject the hospital’s confused reading of Texas law.

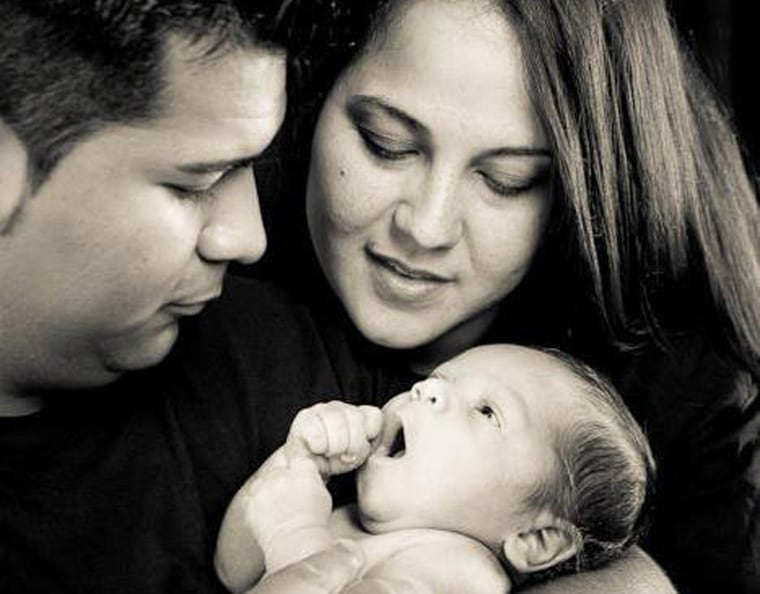

Marlise Munoz was 14 weeks pregnant when she collapsed in her home in November from what doctors believe was a pulmonary embolism. Her husband, Erick Munoz, says doctors have described her as brain-dead and his wife was clear that she would not want to be kept alive in those circumstances.

So why is Marlise still on machines? The hospital says their hands are tied. They say a section of the Texas Advance Directives Act that reads, "A person may not withdraw or withhold life-sustaining treatment under this subchapter from a pregnant patient" leaves them no choice but to ignore the wishes of her husband and family to get the machine turned off. The hospital plans to keep Marlise on life support until the baby comes to term and is able to be delivered via C-section. When that will happen is not clear.

The hospital, however, is very confused. If Marlise is dead, then the Texas law does not apply. Even the legislature of Texas cannot compel continued use of medical interventions on a dead body. “Life support” technology need not be continued if the patient is dead.

Erick Munoz made that case in his lawsuit against John Peter Smith Hospital.

"In fact, Marlise cannot possibly be a 'pregnant patient' — Marlise is dead," the suit says. "To further conduct surgical procedures on a deceased body is nothing short of outrageous."

But even if Marlise were alive — assuming she has either a terminal or irreversible condition — the hospital has the choice to do the right thing ethically, follow the wishes of her husband and family and stop intervening.

The Texas Advance Directives Act is only an immunity statute; it rewards favored behaviors with legal immunity. If the hospital acts “under this subchapter,” it gets civil, criminal, and administrative immunity. If the hospital does not act “under this subchapter,” it is outside the Advance Directives Act and loses the immunities the Act provides. There is no penalty stated for failing to comply with the law, and no guidance about who should try to punish the hospital if it did lose immunity.

And there are plenty of reasons to stop treatment, even given concern for the fetus. Medical experts agree that trying to bring a fetus to term in a dead body is highly “experimental.” The right to say no is a fundamental right governing any and all experimental interventions. In addition, sadly, there is a good chance that when the mother went without oxygen, so did the fetus, and thus a strong chance that the fetus is in poor health. The legislature ought not be compelling a husband and a family if they do not wish a pregnancy to proceed facing long odds.

What’s more, the Texas legislature has made no provision for paying for the care of the fetus, or the care of Marlise’s body — which in an ICU might run to $10,000 a day or more.

The situation in Texas is both illegal and immoral. If Marlise Munoz is dead, then the hospital should have released her body to her family weeks ago. The legal system should ensure that this happens.

Arthur Caplan, Ph.D., is head of the Division of Medical Ethics at NYU Langone Medical Center. Tom Mayo is an Associate Professor at Southern Methodist University/Dedman School of Law.