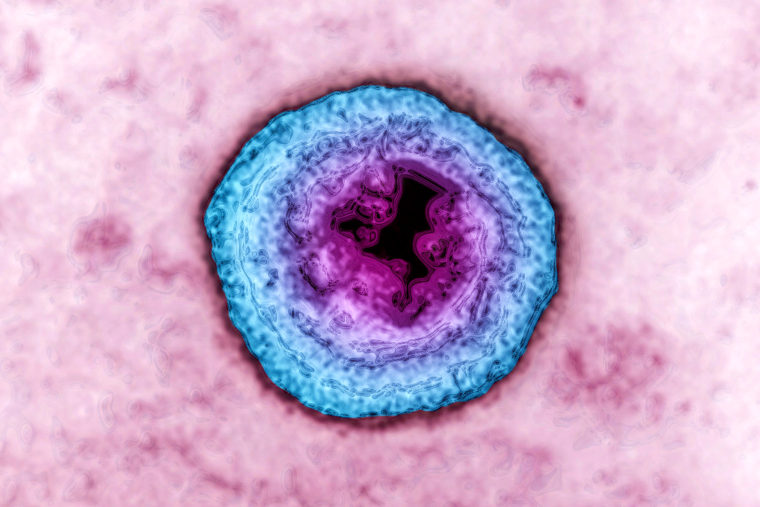

Billions of people around the world are living with herpes infections, prompting the World Health Organization to call for a vaccine against the incurable virus.

About half a billion people ages 15 to 49 have genital herpes infections, which are mostly caused by herpes simplex virus type 2, which can raise the risk of HIV. Herpes infections can lead to recurring, often painful, blisters. Genital herpes infections plays a significant role in the spread of HIV globally, WHO researchers said in a report released May 1.

In 2016, two-thirds of the world's population under 50 — about 3.7 billion people — had herpes simplex virus type 1, which most commonly appears as cold sores in or around the mouth, according to WHO.

"A vaccine against HSV infection would not only help to promote and protect the health and wellbeing of millions of people, particularly women, worldwide, it could also potentially have an impact on slowing the spread of HIV," Dr. Meg Doherty, director of the WHO's global HIV, hepatitis and sexually transmitted infections programs, said in a statement.

Most cases of genital herpes involve HSV-2, WHO researchers reported. HSV-1 is usually spread by kissing, but it can also be transmitted to the genital area through oral sex. As many as 192 million people worldwide have genital HSV-1 infections.

Download the NBC News app for breaking news and alerts

Antiviral treatments can reduce outbreaks of genital herpes, but they aren't a cure.

While the COVID-19 pandemic has led to an unprecedented race to develop a vaccine to protect against the coronavirus, researchers have been trying to come up with a vaccine to prevent herpes for at least four decades. A vaccine that would protect against both strains of herpes has been a challenge, because the virus has been very good at evading the immune system, said Charles Rinaldo, professor and chair of the department of infectious diseases and microbiology at the University of Pittsburgh Graduate School of Public Health.

"As we learned more, we realized it's not a simple matter," Rinaldo told NBC News. "Many have tried to come up with vaccines that use two or three proteins out of the approximately 75 that make up the virus. Those would be quite safe, but in most cases they have not protected well."

Another approach has been to use a weakened form of the whole virus, Rinaldo said. "In that case, the virus is 'attenuated,' which means that its replication capacity is weakened," he said. "It's great from an immunity standpoint, but it's not as safe. It can create problems if it enters the nervous system."

Those failures "are why this is such a monster," Rinaldo said. "Many companies have shut down their herpes vaccine programs."

Sanofi Pasteur Inc. is moving ahead with a vaccine called HSV529, Rinaldo said. "That's based on an attenuated virus. They've taken out two proteins that are essential for the virus to replicate efficiently. The virus replicates poorly and apparently doesn't cause lifelong infection."

Other vaccine candidates are in the works, with at least one showing positive results in mouse models, Rinaldo said.