There’s more evidence that speaking a second language can delay the onset of dementia later in life — this time in a population where even illiterate people reaped the benefits of being bilingual.

Conducted in Hyderabad, India, the largest study of its kind so far found that speaking two languages slowed the start of three types of dementia — including Alzheimer’s disease — by an average of 4.5 years.

“Being bilingual is a particularly efficient and effective type of mental training,” said Dr. Thomas H. Bak, a researcher at The University of Edinburgh and a co-author of the study published Wednesday in the journal Neurology. “In a way, I have to selectively activate one language and deactivate the other language. This switching really requires attention.”

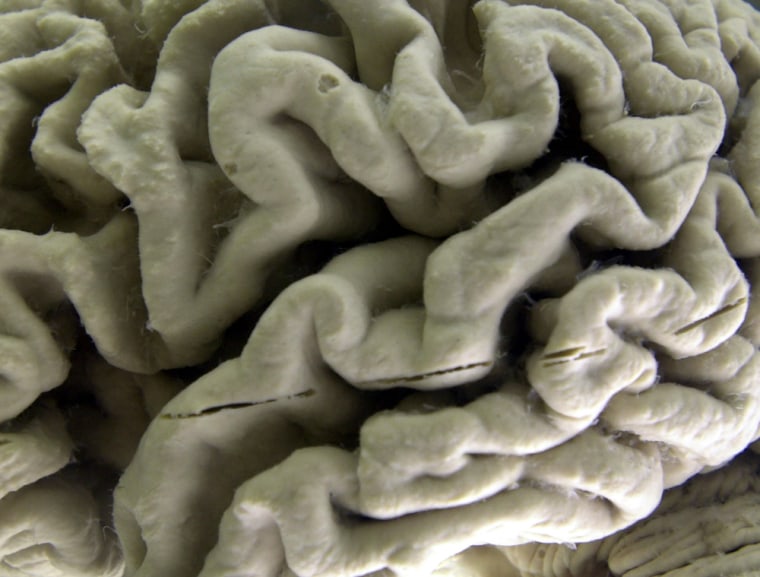

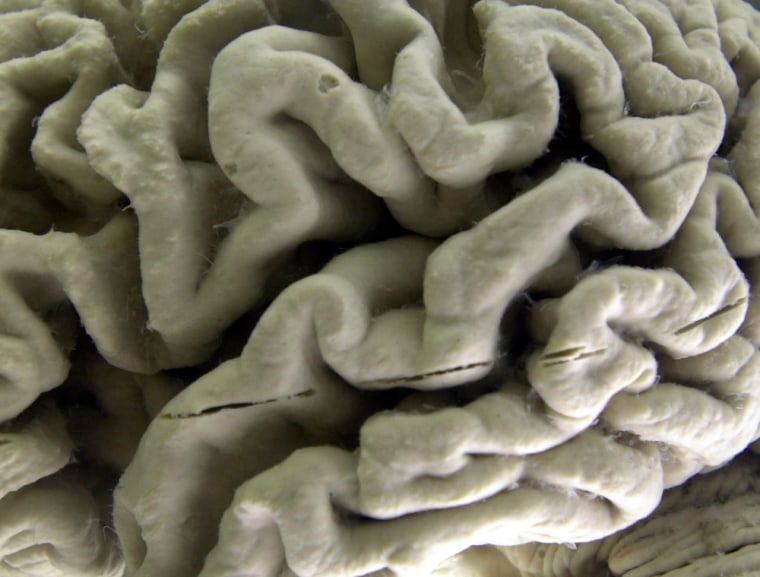

That kind of attention keeps the brain nimble and may ward off not only Alzheimer’s disease, but other cognitive conditions such as frontotemporal dementia and vascular dementia, the new study found.

Bak is part of the team led by Dr. Suvarna Alladi, a professor of neurology at the Nizam’s Institute of Medical Sciences in Hyderabad. The researchers examined case records of 648 patients with dementia who entered a memory clinic at a Hyderabad university hospital between June 2006 and October 2012.

Slightly more than half of the patients, some 391, spoke more than one language in a place where many people grow up learning three or more languages, including Telugu and Dakkhini along with English and Hindi.

Previous studies have focused on the impact of bilingualism on dementia mostly in immigrants in Canada, which may have influenced the results, Bak said.

“It really brought up the question, is it the bilingualism or is it is being an immigrant?” he said. “They have very different lifestyles, very different diets, which can affect the outcome.”

Still, those studies also found that speaking more than one language delayed dementia by the same span of time, four to five years.

The Indian patients offered a chance to examine the issue in a society where many people are naturally multilingual and shift easily among different languages in different social settings.

“If I live in Hyderabad, I am practically always switching,” said Bak. “There will not be a day when I don’t have a chance to practice.”

The researchers found that patients who spoke a single language developed the first symptoms of dementia at age 61, versus age 65 ½ in those who were bilingual. The delay was slightly more than three years for Alzheimer’s disease, but about six years for frontotemporal dementia and about 3.7 years for vascular dementia.

In people who couldn’t read, the delay of dementia was about six years later in those who were bilingual versus those who spoke only one language — evidence that education isn’t the key in postponing problems, the researchers said.

The effect of bilingualism on dementia onset was independent of other factors including education, gender, occupation and whether patients lived in urban or rural areas, the authors said.

Speaking more than two languages didn’t appear to increase the effect, a result that surprised researchers, Bak said. Other studies have found that the more languages spoken, the greater the protection against dementia.

An outside expert who documented the first physical effects of the delay of dementia in people who speak more than one language praised the new study.

“Being able to show that immigrant status was not a factor answers one remaining question, said Dr. Tom Schweizer, a neuroscientist at St. Michael’s Hospital in Toronto, Canada, who found in 2011 that bilingual people have twice as much brain damage as those who speak one language before they show signs of Alzheimer’s disease.

“The fact that the illiterate subjects were also showing this strong effect was also novel,” he added.

It’s still not clear exactly how language acquisition triggers protection against dementia, or whether another kind of intense brain activity such as learning an instrument or doing puzzles could mimic the effect, Schweizer said.

Going forward, conducting dementia research in other non-Western cultures will be key to understanding the effect of bilingualism on dementia, the authors of the new study said.

“For me, the most important message is that you cannot do all the studies in the same place,”Bak said. “In completely different contexts, in complete different populations, we found the same effect.”

JoNel Aleccia is a senior health reporter with NBC News. Follow her on Twitter at @JoNel_Aleccia or send her an email.