On Valentine’s Day 2017, Ebony Boyd picked up some holiday doughnuts as she headed to work feeling “blessed and happy,” she recalls. She was six months pregnant and excited to be having a baby whom she and her boyfriend had already named.

But a few hours after she got to work, Boyd, 36, started feeling excruciating pain. Her doctor suggested that she head for a hospital emergency room. Once there, “they checked for my baby’s heartbeat and there wasn’t any,” Boyd said.

Boyd barely had a chance to begin to grieve her loss when she started hemorrhaging badly. Her blood pressure skyrocketed. Two transfusions later, Boyd started to stabilize.

But just as she was about to be discharged from the hospital three days later, she developed a pulmonary embolism. “They told me if I had been sent home I might not have made it to the next day,” sBoyd, who lives in the Bronx, said in a recent interview.

Boyd could easily be one of the data points in a new study released on Wednesday. It found that African- American women like her, along with women of other minority groups, are far more likely to experience severe, life-threatening complications related to giving birth than white women.

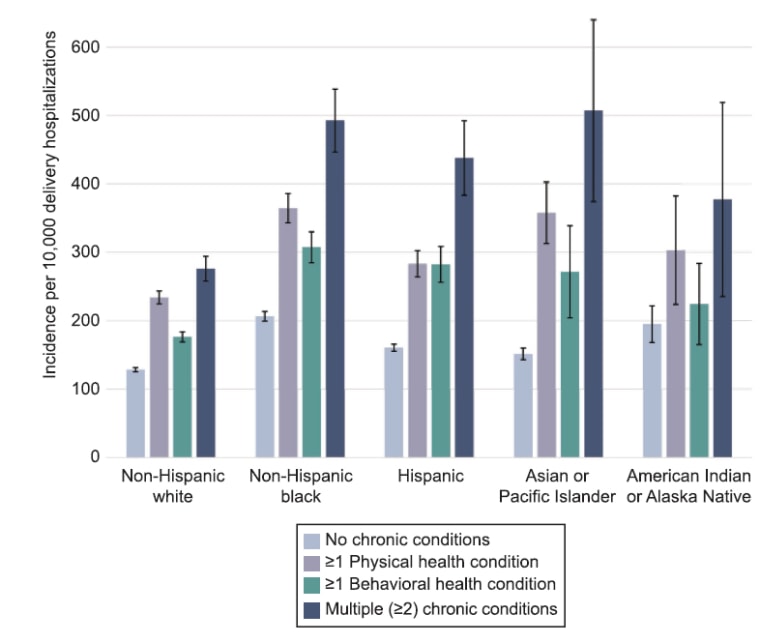

One factor may be the high prevalence of health problems such as high blood pressure in minority women, which can become dangerous when a woman is pregnant, according to the study, published in Obstetrics & Gynecology.

“It’s important that we identify racial and ethnic minority women with chronic conditions as a high-risk group,” said the study’s lead author, Dr. Lindsay Admon, an assistant professor in the department of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of Michigan. “The trends we’re seeing now are startling. They’ve gotten some national attention directed towards the health of new mothers.”

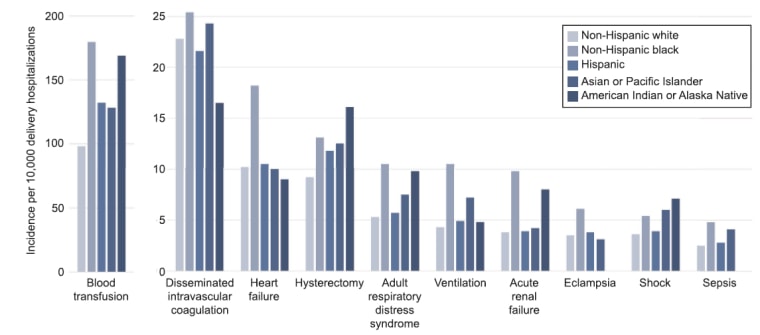

The big concern is maternal death, which also hits minorities harder than whites. Deaths are hard to study, though, because there aren’t that many of them each year. So Admon and her colleagues focused on severe, life-threatening complications that could kill a woman if she didn’t get the right care at exactly the right time. The researchers figured that by scrutinizing more than 40,000 severe complications they might see ways that the care of moms-to-be could be improved and deaths related to delivery reduced.

Recent studies that have found mortality rates due to pregnancy complications on the rise have spurred some officials into action. This week, a bipartisan group of senators sent a letter to Health Secretary Alex Azar saying, “This troubling trend makes the United States an outlier among every other developed country.”

Admon and her colleagues pored over data from more than 2.5 million birth hospitalizations over four years, from 2012 to 2015, which constituted a representative sample of the nearly 13.5 million total births in the U.S. over that same time period.

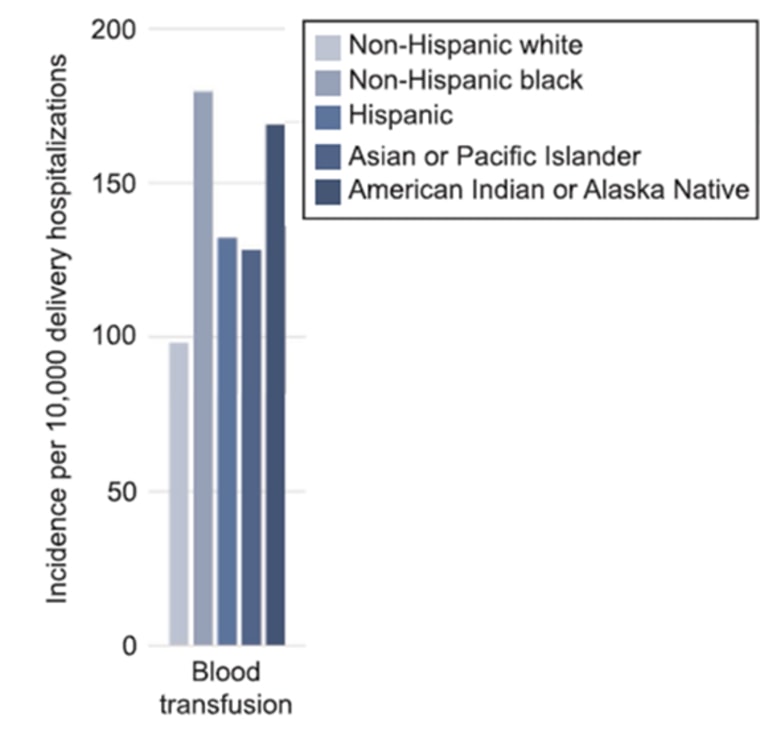

The researchers found that non-Hispanic black women had a 70 percent higher rate of major birth-related problems compared with non-Hispanic white women. Compared with non-Hispanic white women, Hispanic, Asian or Pacific Islander, and American Indian or Alaska Native women also had higher rates of severe complications.

“Recognizing that these disparities exist, it behooves us to figure out how to decrease the disparities,” said Dr. Alan Peaceman, chief of maternal-fetal medicine at Northwestern University’s Feinberg School of Medicine and chief of obstetrics at Northwestern Memorial Hospital. “The numbers here are concerningly high.”

Women of any race or ethnicity who had a chronic health condition, such as asthma, diabetes, kidney disease or high blood pressure, before giving birth were at a higher risk of severe delivery-related complications. Black women who had two or more chronic health problems were nearly three times as likely as those with none to have a severe complication related to birth, the study found.

Getting those chronic health conditions under control before a woman becomes pregnant or early in the pregnancy may be the key to reducing severe complications and maybe also deaths, experts say.

“The authors speculate that management before and after delivery would make a difference,” says Dr. Andrew Satin, a professor and director of gynecology and obstetrics at Johns Hopkins Medicine. “And I agree with that. What we really need to address is getting the patient in optimal shape before she becomes pregnant and then managing her chronic health conditions.”

Dr. Kirsten Lawrence Cleary agrees that ideally, women should get healthy before becoming pregnant. But even if doctors don’t see a patient until after she’s conceived, a lot of serious complications can be avoided if chronic health issues are “evaluated and managed very closely during pregnancy and postpartum,” said Cleary, an assistant professor and a maternal-fetal medicine specialist at NewYork-Presbyterian-Columbia University Medical Center.

That’s what Cleary’s strategy was with Boyd.

When Boyd learned she was pregnant again last November, she went back to the hospital that treated her on Valentine’s Day, NewYork-Presbyterian, which had started a new program focused on high-risk moms-to-be called the Mothers Center. The center's aim is to treat these moms for conditions that could make delivery dangerous with the goal of reducing severe complications and deaths.

That seems to have worked for Boyd. With her blood pressure under control, pregnancy this time “was pretty much smooth sailing all the way through,” she said. “It was really, really good.”

In July, Boyd gave birth to a baby girl. She and her boyfriend named her Janiyah S’Mori Darden.

Though her story ultimately had a happy ending, she wants to share it “because I don’t think a lot of women know the risks, especially minorities,” she said. “I want women to look out for the signs and to be comfortable getting a second opinion. There are two lives at stake, not just one.”