Sherisa Rivera and her husband, Will Rivera II, will never forget the first and only time they saw their baby's heartbeat on an ultrasound. After two unexplained miscarriages, the flutter on the screen at Sherisa's obstetrician's office about seven weeks into her third pregnancy was a welcome sight.

The Bloomfield, Connecticut, couple had no idea that less than 24 hours later, on Will's birthday in September 2017, Sherisa would miscarry again.

"At that point, we were just desperate for answers," Sherisa, 33, said. "We had been told this is bad luck, miscarriage is very common. But now this has happened three times."

While miscarriages occur in up to a quarter of known pregnancies — and about 1 percent of women experience three or more miscarriages — it is rare for patients to learn the reason why. Chromosomal abnormalities are by far the most common cause, but genetic tests on fetal tissue cost thousands of dollars, and results can take weeks. In most cases, genetic testing is not even offered until a patient has had three or more miscarriages.

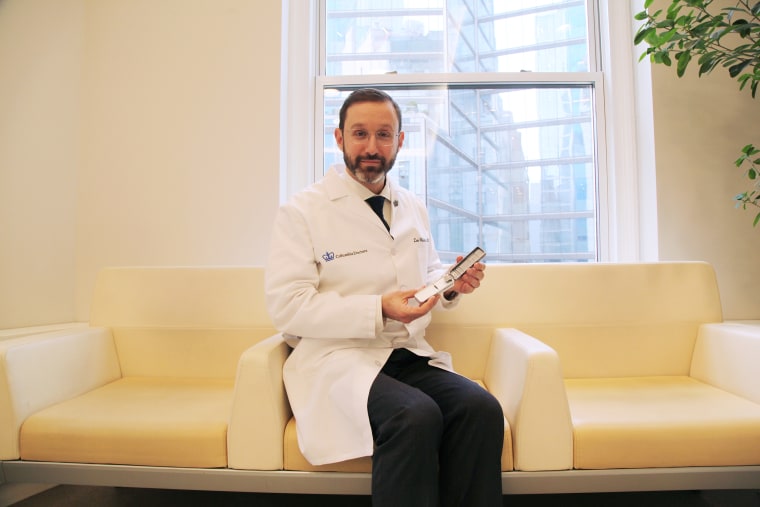

Advances in rapid genetic testing may change that. By combining several new technologies, Dr. Zev Williams, director of the Columbia University Fertility Center in New York, has developed what he says is a faster, cheaper method to test fetal tissue for genetic abnormalities.

The new method takes just four hours and costs less than $200. Williams has begun publishing research on his technique; more is expected to appear this month in the peer-reviewed journal BioTechniques.

"Pregnancy loss has really been, from a patient's point of view, incredibly devastating to be going through, but from a medical and scientific point of view, a black box," Williams said. "We're starting to chip away at that."

The rapid test wouldn't resolve all the questions around miscarriage. But it would give answers much faster to many grieving patients and their doctors.

Experts such as Cynthia Casson Morton, a medical geneticist at Brigham and Women's Hospital in Boston, said after reviewing Williams' research that the method looked promising. But she wasn't sure whether couples would want an answer that quickly: "It's a lot of information to handle all at once while they're grieving," Morton said.

Dr. Christine C. Greves, an obstetrician-gynecologist at Orlando Health Winnie Palmer Hospital, agreed that not everyone would be ready to hear test results right away, but she believed many would.

"Our human nature is wanting to know why," she said, "so if we could know why sooner, and it's accurate, then that probably could provide more of a sense of peace."

The mysteries of miscarriage

There's a lot scientists don't understand about miscarriages, especially since some women miscarry so early, they never knew they were pregnant.

Experts believe at least half of early pregnancy losses are due to genetic abnormalities. Other causes include blood clotting disorders, thyroid imbalances and structural problems in the uterus.

Doctors can run an array of tests to determine the cause, but regardless of the findings, women often blame themselves, said Dr. Scott A. Sullivan, director of maternal-fetal medicine at the Medical University of South Carolina. A 2015 study found 47 percent of women reported they felt guilty after a miscarriage and 41 percent felt as though they had done something wrong.

"They say, 'Oh, I shouldn't have had that margarita at eight weeks,' when you didn't even know you were pregnant. Or 'I worked double shifts,'" Sullivan said, even though studies do not indicate that a single drink or moderate stress can contribute to miscarriage.

Sherisa Rivera's miscarriages have led her and her husband to question nearly every aspect of their lives. Sherisa has wondered whether she should have skipped a flu shot she got just before one of her losses, even though there is no increased risk of miscarriage associated with the flu shot. The couple went vegan for six months. They no longer use fragrance in their laundry detergents.

But they have now had five pregnancy losses, most recently in April.

The couple was only able to do fetal genetic testing after their third miscarriage, a $6,000 test that Sherisa's health insurance fully covered only after a lengthy battle.

Nineteen long days after the doctor sent the tissue away for testing, the Riveras learned that their unborn child had trisomy 22, a chromosomal disorder that almost never results in a live birth. Experts say it is a rare condition that is not necessarily likely to happen twice in women who are trying to conceive, and does not indicate that Sherisa's other losses were due to the same cause.

"It gave me peace of mind in that I knew my child was not going to suffer," Sherisa said. "It did not remove the fear, anxiety and trauma that I had experienced."

The pocket-size device that will do the test

The device Williams uses for genetic testing looks like a miniature stapler. Developed by Oxford Nanopore Technologies, which is headquartered in the United Kingdom, it became commercially available in 2015 and has been used in a variety of research applications, including outbreaks such as the current coronavirus epidemic.

Williams and his team believe they would be the first to use it to read the letters that comprise the genetic material of either the fetus or the placenta following a miscarriage. His innovation is in the way he sped up each step of the process: extracting the DNA from the tissue sample, preparing it for sequencing and analyzing the results.

If the test reveals chromosomal abnormalities, Williams believes it will make couples less inclined to blame themselves. (A simple blood test can be done on the parents to make sure neither of them has a chromosomal issue that would make the genetic problem likely to recur; if they do, screening embryos first through in vitro fertilization would be a solution to make sure only healthy ones are placed in the uterus.) If the fetal genetic test comes back normal, that's a clue that doctors should explore nongenetic causes, such as a malformation of the uterus or a hormonal issue.

The test will not work in all cases — if the miscarriage happened so early that there is no tissue to sample, for instance — and still might not always be covered by insurance.

After developing the method over five years, Williams and his research team recently did a trial with samples from more than 50 women and are submitting the data to the New York state Health Department for approval. He has a patent on the method of preparing and testing samples and anticipates he will work with a commercial partner to offer it to doctors across the country, but he will start with a small number of patients at Columbia University Fertility Center. Eventually, he hopes to further lower the cost.

"The driving force is much more the ability to help and give answers," he said.

'All my husband and I were looking for was an answer'

For some couples, genetic testing has only led to more questions.

A couple years after having their son, now 13, Kate Powers, of East Lansing, Michigan, and her husband started trying to conceive again. That began a heartbreaking seven-year odyssey of four miscarriages followed by an ectopic pregnancy, a rare condition in which a fertilized egg grows outside of the uterus, making it impossible for the embryo to survive and potentially threatening the mother's life.

After Powers' second loss, her obstetrician suggested fetal genetic testing. Following the several-week wait that is common, results came back. They were normal.

"All my husband and I were looking for was an answer," Powers, 42, said. "Even if it was something that was horrific and it would be something that would occur again, even if in that moment I would receive that genetic testing back and they were like, 'It is a very bad idea for you to have another child,' I think even that would be easier for me to digest."

They still do not know what caused their losses. After her ectopic pregnancy, Powers realized her efforts to have another child were endangering not just her mental health but also her physical health, and it became clear to her and her husband that it was time to stop trying.

The Riveras still hope to have children someday.

They have chosen the room in their three-bedroom house that will eventually become the nursery. In their home, they have tiny wood figurines dressed in white to commemorate their losses: a child grasping a balloon that reads "hope," a woman holding her pregnant belly and a mother with angel wings embracing a young child.

Their experience has taken a deep toll. Sherisa, a former administrative assistant for a church, became a substitute high school teacher because she has not felt able to work consistently. The couple started a support community, Fertility In Colour, that aims to connect others — especially people of color like themselves (Sherisa is a black British native, and Will is Hispanic) — who are going through recurrent miscarriages or infertility. They want to encourage people to openly speak about pregnancy loss.

Last month, the couple had their first appointment with Williams, who is running more thorough bloodwork and other tests on them. Someday, Sherisa hopes to tell her future children about the struggles it took to have them.

"I hope to have healthy children that know they are loved based on the hardships we have had to endure to get them here," Sherisa said. "We've come too far to hide it."

This article is part of a series on pregnancy loss. For more, go to TODAY.com/miscarriage.