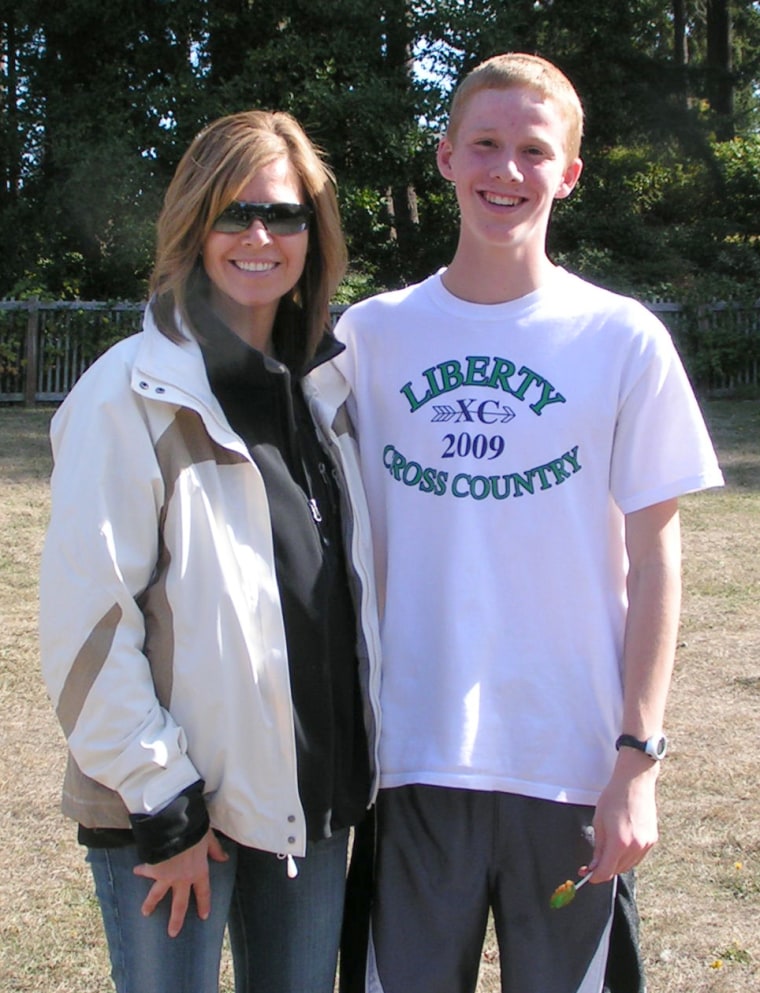

Steve and Dawn Thomas rarely saw their son Brandon blush, and if they did, it wasn’t a worry.

Brandon was blond and fair, like his twin brother, Devin, and an occasional flush of color didn’t seem concerning.

“We wouldn’t have witnessed it,” said Steve Thomas. “It wasn’t even happening here at home. I think this was his place of comfort.”

So they were stunned last fall when Brandon, a friendly, well-liked University of Washington student, confessed to his mother he’d been struggling with crippling, chronic blushing for four years.

And they were devastated on May 29, when Brandon jumped from the 11th floor balcony of his Seattle dormitory, leaving behind a five-page note blaming his suicide on despair caused by the little-known disorder.

“When Brandon finally let us in to his secret life of torment, we were obviously way behind,” his mother said.

Six weeks later, the Thomases are speaking out about Brandon’s death to honor his last wish. In the letter, the young man who hid the problem from his friends, his family -- even his twin -- wanted the world to know that there’s nothing trivial about turning red.

“One of the reasons he took his life is that if he took this drastic measure, it would raise awareness,” Dawn Thomas said. “He wanted his death to have an impact.”

To that end, Dawn, 45, Steve, 47, and Devin, 20, are seated on a couch in the family’s manicured lakeside home in Renton, Wash., just outside Seattle, stoically facing a reporter’s notebook and a video camera. Dawn, who works at nearby Microsoft, and Steve, a firefighter, wanted to set the record straight.

“I’ve had people come up to me, even at his service, and say ‘I know, I blush, too, when I’m in public,’” said Dawn Thomas. “That is not what this is about.”

Instead, they say that Brandon was fighting a daily battle with what experts describe as pathological blushing, facial reddening that goes far beyond the typical flush most people feel at committing a social faux pas or speaking in front of a group.

An estimated 5 percent to 7 percent of the population may suffer from chronic blushing, an uncontrollable reaction triggered by an overactive nervous system and compounded by the fallout of social shame. That’s according to Dr. Enrique Jadresic, a Chilean psychiatrist and the world’s foremost expert on the disorder, who also suffered from it himself.

“Blushing, which presumably is a minor symptom, can erode not only self-esteem, but also the will and desire to live,” said Jadresic, the author of a 2008 book on the condition, called “When Blushing Hurts: Overcoming Abnormal Facial Blushing.”

There are ways to treat chronic blushing, including hypnosis, therapy, anti-anxiety drugs and, for some, a controversial surgery that snips or clamps the nerve in the torso that controls flushing. But like Brandon, many so-called blushers suffer silently, ashamed to admit to the condition that colors work, romance and other crucial parts of life.

'No, mom, you need to just go look it up'

When Brandon called his mother in tears last fall, she knew only that it was serious -- and that he must have been desperately in need of help.

“I was sitting there trying to make sure I chose my words carefully: ‘OK, Brandon, you know we all blush,’” Dawn Thomas recalled. “And he said, ‘Mom, no, you need to just go look it up.’”

Online, she discovered what Brandon had found: blogs, anecdotal reports and a few scientific studies that described people for whom routine blushing had become unbearable.

“The biggest thing for him and the biggest thing for all the people who suffer with chronic blushing is the shame,” she said. “People do think of it as trivial because we all blush. And what’s the problem?”

At first, the problem isn’t even the blushing itself, Jadresic said in emails to msnbc.com. Around puberty, some people with a heightened sympathetic nervous system, the network that controls involuntary actions like sweating and blushing, seem to start to blush more, but without the social cues such as embarrassment that typically trigger a blush.

Blushing occurs when the tiny blood vessels of face, called capillaries, widen, allowing more blood to flow through them, causing the skin to redden. The widening occurs in response to signals sent from the brain through the nerves. It's an involuntary action often sparked by strong emotions, such as embarrassment or anger, but also can be caused by spicy foods and alcohol. In chronic blushers, though, there may be no obvious trigger.

That was the case with Brandon, who started blushing around age 15. Without warning, he'd flush bright red from his neck to his ears.

“He would be laughing with people and someone would point out, ‘Oh, look how red Brandon’s getting,’” said Dawn Thomas, recounting what Brandon had told her. “And he’d be thinking, ‘I am?' Because he didn’t realize he was turning red.”

The color was noticeable, said Troy Colyer, 20, who had been friends with Brandon since middle school and attended the University of Washington with him. But Brandon was such a funny, energetic guy, well-liked by everyone, that it didn't draw too much attention.

"He used to blush, but we didn't think much of it," recalled Colyer, who organized a vigil after Brandon's death attended by at least 100 people. "People thought it was cute and funny."

'He was the last person in the world you'd think would do this.'

Some friends may have joked about the blushing, but it was never mean-spirited; no one ridiculed Brandon, Colyer said. He and others were stunned to learn that Brandon was suffering.

"He was the last person in the world you'd think would do this," Colyer said.

What no one knew, Brandon's mother said, was that when anyone pointed out the blushing, Brandon became embarrassed. And then he started dreading the blushing he couldn’t control, leading to what experts call “erythrophobia,” or fear of blushing.

“Since it’s visible and uncontrollable and frequent, you are always on the alert. You dread blushing or the possibility of it happening,” Jadresic explained.

Doctors, psychiatrists and others have long debated the source of chronic blushing. For years, professionals thought it was a psychological issue.

“The view was that the main problem was in the blusher’s mind, in the way the blusher thought about the blush,” Jadresic said.

More recent research has suggested that it actually is based in biology, Jadresic said.

“Clearly, we do not all blush the same, to the same extent and severity,” he noted.

When people blush more frequently and intensely than normal, it can trigger severe psychological and social reactions, Jadresic said. Sixty percent of blushers in one study and 90 percent in another study met the diagnostic criteria for social anxiety disorder, or SAD, he added.

'I am tired of blushing.'

Regardless of the cause, chronic blushing can cripple a sufferer’s life. In his last letter to his parents, Brandon tried to explain how the disorder dominated him.

“I blush several times a day. It doesn’t have to be when I am embarrassed either,” he wrote.

He would blush in class, on the phone, while driving in his car, late at night when he recalled blushing during the day. He would take the stairs instead of the elevator from the 11th floor in order to avoid meeting someone he knew entering the elevator on the way down, which he knew would trigger a blush.

All of this agony was kept secret, Brandon's friends and family say. The business major who hoped to be a firefighter like his dad was outgoing and loved sports, especially basketball and soccer. He and his brother had a longstanding rivalry about the Huskies vs. the Cougars, the mascots of the state's warring college teams. When Devin left for school at Western Washington University in Bellingham, a couple hours north of Seattle, the brothers were in frequent contact. "We texted a lot," said Devin.

With friends, Brandon was something of a peacemaker, his friend Troy Colyer recalled.

"He was the glue that kept everyone together," he said.

Outwardly, there was no sign of the young man whose last letter reported that he cried himself to sleep nearly every night.

“I am tired of blushing,” Brandon wrote. “It is exhausting to wake up every day and have to find little ways to avoid blushing situations.”

Desperate efforts

Once they knew about the problem, Brandon’s family tried desperately to get him help. In April, they took him to doctors, found a counselor, got prescriptions for low doses of anti-anxiety drugs and beta-blockers, which have been successfully used to treat blushing. They discussed the possibility of endoscopic thoracic sympathectomy, or ETS, the controversial surgery sometimes used to treat both excessive sweating, or hyperhidrosis, and pathological blushing.

Jadresic, who had the surgery himself, believes that it can be an effective cure. He led a study of more than 300 patients published last year that compared surgery, drug treatments and no treatment. Among those treated with ETS, 90 percent reported being either “quite satisfied” or “very satisfied” with the results.

Still, the surgery is controversial. Some patients have reported serious side effects, including unusual sweating or weakness, sometimes without controlling the blushing.

“Health professionals should ensure that surgery is used only as a last resort,” said Jadresic.

Brandon wanted the surgery, but reluctantly agreed to try drugs and therapy first, his parents said. During an anxious meeting in Seattle, a doctor told Brandon the surgery had only a 50 percent chance of success. In response, the family planned to see a new doctor in New York this summer, one who was more familiar with the operation. If that didn't work, they planned to visit an expert in Ireland who claims to cure chronic blushing.

Before they could take those steps, however, Brandon was gone.

“He was so hopeless by the time [he told us],” his mother said. “He believed in his mind that he was never going to have a successful career, and that he would never have a successful relationship because of this.”

Now they’re speaking out about chronic blushing, hoping to create a website that gathers information about the condition all in one place, providing links to Jadresic’s book, which may have provided hope to Brandon if he’d seen it earlier. The website is still under construction. People who want to know more -- or to contact Brandon's parents -- can send an email to info@chronicblushinghelp.com.

With more information, maybe Brandon could have held on long enough to get help, his parents said. As it is, they'll never know exactly why Brandon couldn't wait, or what specific event might have spurred his final action.

“That’s the hard part,” Steve Thomas said. “There are just so many unanswered questions.”

More on Vitals: