Three ancient shells that were forgotten for decades, hidden among rocks and bones in dusty museum archives, may be the world’s oldest known beads, according to a new study.

The shells, originally collected from Israel and Algeria, could be as many as 100,000 years old, and each has a hole through its center, suggesting it was worn as jewelry.

The researchers who rediscovered the shells say they add to a growing body of evidence that symbolic thinking emerged much earlier than previously thought.

In Western cultures today, jewelry may not seem like a fundamental type of cultural expression. But to archaeologists, ancient jewelry is much more than very old bling.

“Personal ornamentation is not trivial at all. Archaeologically, it’s quite important. It’s really a symptom of the emergence of modern culture,” said Francesco d’Errico of Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique Unité Mixte de Recherche (CNRS UMR) in Talence, France.

D’Errico and his colleagues describe their discovery in Friday's issue of the journal Science, published by AAAS, the nonprofit science society.

A revolution in Europe?

Over the years, archaeologists have unearthed a wealth of cave paintings, musical instruments, jewelry and other artwork from around 40,000 years ago in Europe. These finds seemed to represent a revolution of sorts, in which humans, who had long been biologically modern, developed modern behavior.

“Modern” in this sense involves thinking abstractly and understanding symbols. It also means living together in larger groups, making more sophisticated tools and shelters, and eventually, using language.

Throughout modern human history, people have worn jewelry to convey something about who they are, such as their ethnic origin, age or social status, according d’Errico.

“The common element among personal ornaments is that they convey meaning to others. They convey an image of you that is not just your biological self,” he said.

Beads from Blombos

But why should symbolic thinking have sprung up so quickly? Modern humansalso lived in Asia, the Near East and Africa well before 40,000 years ago. And, it isn’t clear what exactly would have ignited the supposed “revolution” in modern behavior once humans arrived in Europe.

Though many researchers still think some important biological change occurred at the 40,000-year mark, they have begun to consider that at least some aspects of modern culture may have had a much earlier start.

“Earlier humans may not have had a material culture as rich as the one in Europe, but cognitive abilities and other expressions of modern culture may nonetheless have already been in place,” said study co-author Marian Vanhaeren of University College London and CNRS UMR in Nanterre, France.

In 2004, d’Errico, Vanhaeren and their colleagues made a discovery that gave a major boost to this idea. They found a collection of shells at Blombos Cave in South Africa that were dated to about 75,000 years ago. The shells had holes in their centers, and even showed evidence of wear caused by being threaded on a string.

As provocatively beadlike as the shells were, they had only turned up at a single site outside of Europe. The researchers would need evidence from other locations in order to draw any firm conclusions about an earlier origin for modern behavior.

Museum treasure hunt

D’Errico, Vanhaeren and their colleagues began sorting through museum collections in search of more evidence for early beadworking.

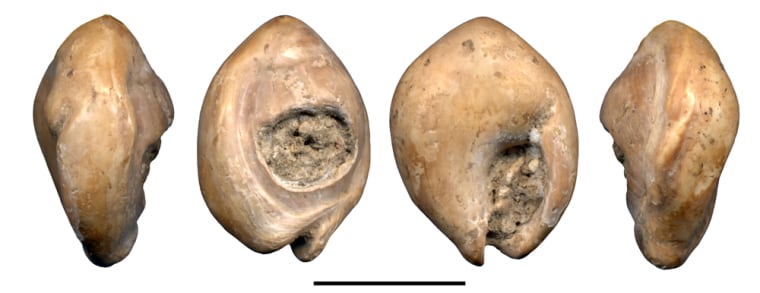

At the Natural History Museum in London, the research team found a pair of shells among the other remains collected from the Israeli site of Skhul in the 1930s by British archaeologists Dorothy Garrod and Dorothy Bate. The shells are from the same genus, Nassarius, as those from Blombos.

The researchers tracked down another perforated Nassarius shell at the Musée de l’Homme in Paris. It had been tucked away in the same small tin since it was discovered at the Algerian site of Oued Djebbana in the late 1940s.

“It was so tiny and packed away with tons of [rock samples]. It could have easily been lost,” d’Errico said.

Oued Djebbana’s age is less clear than that of Skhul, but the technology and style of the stone tools found there suggest that the site could be up to 90,000 years old, according to the authors.

Three small shells, one big idea

D’Errico and his colleagues say that the two sites are so far inland that the shells must have been intentionally brought there.

“This implies that people went to sea and collected them, or more probably exchanged goods with coastal peoples. The indication is that we are dealing with well-structured human culture that attributed meaning to these things,” d’Errico said.

By studying modern Nassarius shells from Mediterranean beaches, they also determined that shells with single holes in the center are rare in nature and that Skhul and Djebbana inhabitants must have purposely perforated or deliberately picked out such shells.

The relatively large size of the shells from the two sites may also help confirm their old age, since this species was bigger 100,000 years ago than it is today, the researchers say.

However, three shells is a small sampling for such a big conclusion, and ultimately researchers will need to find more beads in order to say definitively when this aspect of modern behavior emerged. More discoveries will also allow researchers to investigate whether beadworking was a shared tradition, passed along across cultures, or whether it emerged independently in different places.