Fifty years ago, Sputnik's launch marked humanity's epochal breakout into space, and during the 20 years that followed, engineers created all of the fundamental types of space vehicles and space missions we see today. That amazing burst of human creativity provides lessons that are critical to continued success in space, and arguably on our home planet as well.

Will those lessons make the transition from the "Greatest Generation" of spaceflight to our own generation, and generations to come?

This golden anniversary is a fitting time to take stock of the past, the present and the future of space exploration — and ask some deep questions about how people can handle challenges that are, in the words of NASA Administrator Michael Griffin, "almost too hard for us to do." We need to find out how to make those challenges easier, as well as how to avoid the things that occasionally make it impossible to succeed. And we're not just talking about spaceflight here.

One set of practical questions has profound implications for the future: How were the people of the Sputnik generation smart enough to organize themselves into teams with the skills to succeed? Can the new generations of workers in Russia, the United States and around the world replicate the mind-set of the people who opened the space frontier?

The chances of future success will be slim if the next generation doesn't understand how it was done the first time.

Lots of theories, lots of nonsense

Fifty years ago, many theories to explain Sputnik sprang up almost immediately after the launch, although most were associated with American excuses for not being first, or Soviet boasts about their inevitable primacy in exploring the future. Perhaps we had “captured the wrong Germans” after the Second World War, or had failed to produce enough trained engineers. Perhaps a centrally directed "command economy" was optimal for preparing human minds and for orchestrating diverse resources for a complex goal.

Nonsense, all of it — and what’s worse, dangerous nonsense. That’s because whenever any of those reasons were believed and acted on, wrong decisions were made and resources were wasted as a result. Too much misunderstanding of the "secrets of space success" led to repeated space failures, at horrendous costs in time, treasure, prestige and even human lives. Those who do not learn from the past will repeat its mistakes.

The true secret of rocket science isn't about being smart enough to find the right answers to technological problems. Instead, it's about being wise enough to ask the right questions in the first place.

This is a wisdom acquired both through personal experience and — in rare cases — in learning from the experience of others. It's not about being omniscient enough to manipulate vast resources like an orchestra director, but instead has to do with creating a team culture where each individual is empowered and motivated to contribute their own skills and judgments to the common goal.

First step: Mental preparations

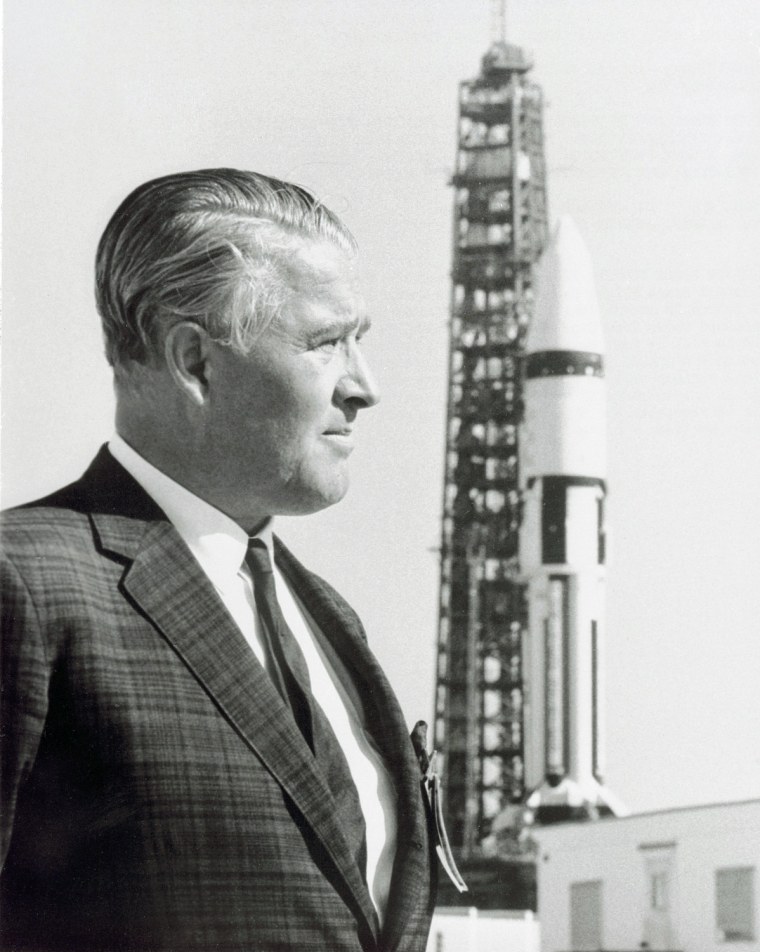

When Wernher von Braun’s V-2 rocket team came from Germany to the United States, they were accompanied by hundreds of tons of metal and documentation about their V-2 experience. But their most valuable cargo wasn’t a secret rocket fuel formula or a gyroscope control equation, or even anything already expressed in hardware or written down on paper — it was their engineering judgment and intuition, which added to the parallel experience base of American rocketeers.

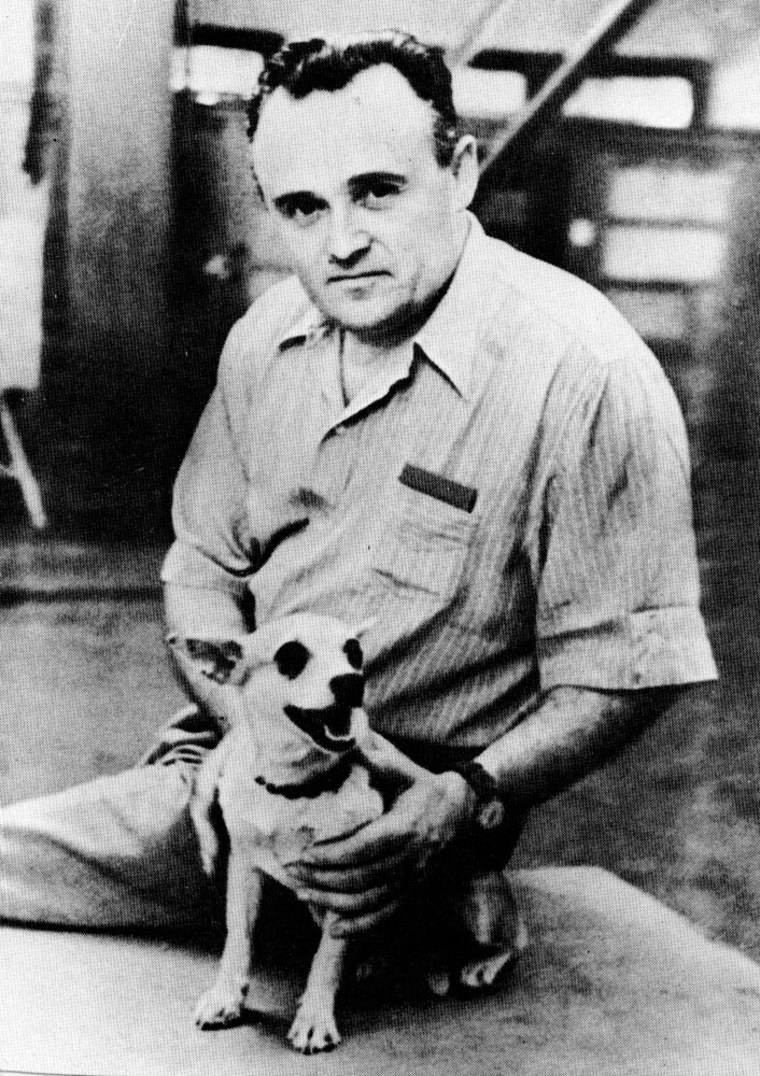

When Sergei Korolyov assembled his rocket team and component developers for the R-7 rocket that would send Sputnik into orbit and open the space frontier, he drew upon his own experience base — aircraft, rocket engines, missile work, more often failures than successes. Next week, the direct descendant of that R-7 rocket, known as the Soyuz launch vehicle, will once again carry cosmonauts into orbit.

The mental preparations made by von Braun and Korolyov proved critical, because space technology development is generally not a process that pushes forward on one well-defined technological theme at a time. More often, the innovators have to select among alternative solutions to an unbroken avalanche of problems.

These problems must be detected and recognized as early as possible (“Keep asking questions about what is working, or not working”). The assortment of feasible solutions must be as wide as possible (“What’s going on in that other shop that could help this one’s problems?”). There must be a measurable way to evaluate the options (“What are the costs, and benefits, to such-and-such approach?”). There must be a continuous oversight to verify the level of success of each solution as it is being implemented (“Did the latest test measure up to promised performance?”).

Junior engineers can be sent off to answer these well-defined questions, but the program managers have to have the engineering judgment to ask the questions in the first place.

Sizing up the space powers

This is the cultural challenge facing future generations of space workers, and the next half-century will demonstrate how well the legacy of Sputnik (and of Apollo) really survives.

In Russia, the men of the old guard, who began as apprentices to the masters and who now are finally retiring (or dying at their posts), are making way for a massive power shift to a younger cadre of leaders who have lived in their shadows for decades — not the kind of environment that nourishes a passion for asking questions.

In the United States, the demographic transition has been managed better, and active "lessons learned" programs have sought to squeeze out the brains of the old-timers for useful insights that youngsters could read about — even as those next-generation engineers perform repetitive spaceflight operations with little scope for developmental creativity and judgment.

Slideshow 12 photos

Month in Space: January 2014

In China, space teams are directed based on a presumptive omniscience of centralized leadership, but they are also committed to learning all they can from the experience of other space programs.

In Europe, a multipolar bureaucracy tends to politicize project decisions, hampering the continent's distributed (and top-notch) expertise in space technology. Transnational funding considerations often trump technical judgment.

In all these cases, and more, the experience of Sputnik needs to live on — not as fossilized history, but as a vivid and vibrant example of how to "do space" right.

The first step in that direction is not obedience to tradition, but intuitive inquiry about choice-making. That's a lesson that can be applied not just to the space industry, but to other industries and entire societies as well.

James Oberg, space analyst for NBC News, spent 22 years at the Johnson Space Center as a Mission Control operator and an orbital designer. He is the author of several books about the U.S. and Soviet space programs, including "Red Star in Orbit" and "Star-Crossed Orbits." Oberg also speaks to high-tech industry workers and managers on space lessons for safety and reliability.