The lines that tie the globe together by carrying phone calls and Internet traffic are just two-thirds of an inch thick where they lie on the ocean floor.

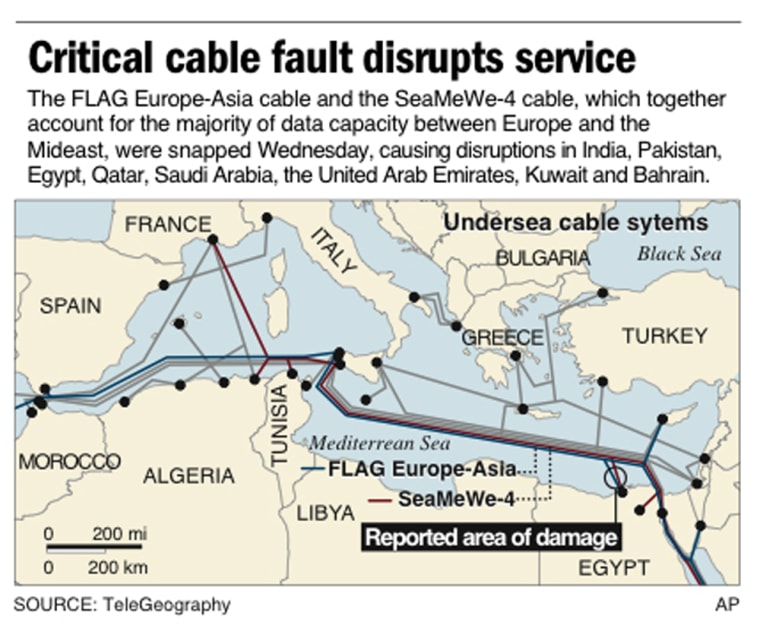

The foundation for a connected world seems quite fragile, an impression reinforced this week when a break in two cables in the Mediterranean Sea disrupted communications across the Middle East and into India and neighboring countries.

Yet the network itself is fairly resilient. In fact, cables are broken all the time, usually by fishing lines and ship anchors, and few of us notice. It takes a confluence of factors for a cable break to cause an outage.

"Most telecom companies have capacity at multiple systems, so if one goes out, they simply reroute to a different system," said Stephan Beckert, analyst at research firm TeleGeography in Washington. "It's just that in this case, both the main route and the backup route got cut for a lot of companies."

The two cables — FLAG Europe Asia and SEA-ME-WE 4 — were cut on the ocean floor just north of Alexandria, Egypt.

By an accident of geography and global politics, Egypt is a choke point in the global communications network, just as it is with global shipping. The reasons are the same: The country touches both the Mediterranean and the Red Sea, which flows into the India Ocean.

The slim fiber-optic cables that carry the world's communications are much like ships, in that they're the cheapest way for carrying things over long distances. Pulling cable overland is much more expensive and requires negotiation with landowners and governments.

So fiber-optic cables that go from Europe to India take the sea route via Egypt's Suez Canal, just as ships do.

Another Mediterranean cable makes land not far away, in Israel.

But there's no cable overland from Israel into Jordan and to the Persian Gulf, which could have provided a redundant connection for the Gulf States and India. Going overland would have been more expensive and politically difficult — Israel and Arab countries would have to cooperate.

There is also no route that goes through Russia, Iran and Pakistan to India. The terrain is rugged, Pakistan is politically unstable, and India and Pakistan are not on good terms.

With two of the three cables passing through Suez cut, traffic from the Middle East and India intended for Europe was forced to route eastward, around most of the globe.

The main route goes through Japan and the United States, crossing both the Pacific and Atlantic Oceans. According to Beckert, this is normally the cheap way to go for Indian traffic, since capacity is high. However, the distance means more time required to reach Europe and get a response.

The other route from India to Europe goes over China into Russia and along the Trans-Siberian railroad.

Egypt is not the only check point in the global network. The ocean just south of Taiwan proved to be one in December 2006, when an earthquake cut seven of eight cables passing through the area, slowing down communications in Hong Kong and other parts of Asia for months.

Another possible vulnerability is the U.S. island of Guam in the Pacific Ocean. It is the spider at the center of a web of cables from the United States, Japan, Australia, the Philippines and China.

Both cables that connect the United States to Australia and New Zealand run over Hawaii, creating another choke point.

These bottlenecks are likely to go away, however, as telecoms build more and more lines. Another U.S.-Australia line is scheduled to be completed soon, according to Beckert, and a U.S.-China line that bypasses Japan is also in the works.

But it will be years before the network across Asia is as resilient as the trans-Atlantic network, where multiple high-capacity lines over different routes provide a connection that's almost impossible to disrupt. And the factors that make the Suez Canal a vulnerable point now will likely remain.

Mustafa Alani, head of the security and terrorism department at the Dubai-based Gulf Research Center, said the outage should be a "wake-up call" for governments and professionals to divert more resources to protect vital infrastructure.

"This shows how easy it would be to attack" communications networks, he said.

Yet the owners of the undersea cables aren't very concerned with terrorism, according to Beckert. They're too busy worrying about fishing boats.

"They want to publish maps of their cables as widely as possible, so fishing crews know where they are," Beckert said. "The risk of accidental cuts is much, much greater than the risk of deliberate cuts."