A baby’s first word is typically a momentous occasion, witnessed with proud smiles and teary eyes. But what of the babbling that comes before? These nonsensical noises may also be a major milestone on the way to learning language, according to a new study in the journal Science, published by the American Association for the Advancement of Science.

Scientists have argued for years over how our ability to use language arose. Babbling, it turns out, may be an important part of the answer.

“It’s a universal behavior of the species, and it’s compelling because it comes on a specific developmental timetable in infancy, just like there’s a specific period in development when our species hits puberty,” said study author Laura-Ann Petitto of Dartmouth College.

The orgins of language

Researchers have been divided, Petitto said, on whether babbling is just a type of motor skill involving the mouth, like crying or chewing, or a preliminary step toward speaking a language and thus distinct from other mouth-made sounds.

“This in turn has very deep implications for our understanding of the evolution of language,” said Petitto.

The different views on babbling reflect a larger divide over why humans communicate using words, while other species don’t. Some experts believe that we began speaking essentially by accident, perhaps after our ancestors noticed they could make different sounds while moving their jaws. Others believe that language is one of the key things that define us as human, and that our brains have been “hard-wired” for language all along.

Petitto and Siobahn Holowka of McGill University in Montreal wanted to test the hypothesis that babbling is merely “mouth flapping,” which fits with the idea that language arose as a random or accidental event. If babbling turned out to be language-related instead, it would support the argument that the human brain is specially designed for speaking language.

A major challenge was how to test the infants without harming them.

“You don’t want to put young babies in a brain scanner,” Petitto said.

Instead they used the mouth “laterality index,” which is a fancy way of saying lopsidedness. Researchers have long known that, when we talk, our mouths open just a little more on the right side than the left. That’s because the brain’s language machinery is in the left hemisphere, the side that also controls the right side of the face.

We don’t notice this effect when we look at someone speaking, according to Petitto, because our eyes automatically correct unevenness and asymmetry in the scenes we see. But, if you look in your bathroom mirror, and talk while holding a hand mirror at the correct angle, you can see the lopsidedness for yourself.

Over the last thirty years, researchers have developed the laterality index as an objective measurement system for determining the degree of “right asymmetry” during someone’s speech. Typically, it was used to quickly identify brain damage in stroke or heart attack victims, according to Petitto.

Babbles, smiles, and videotape

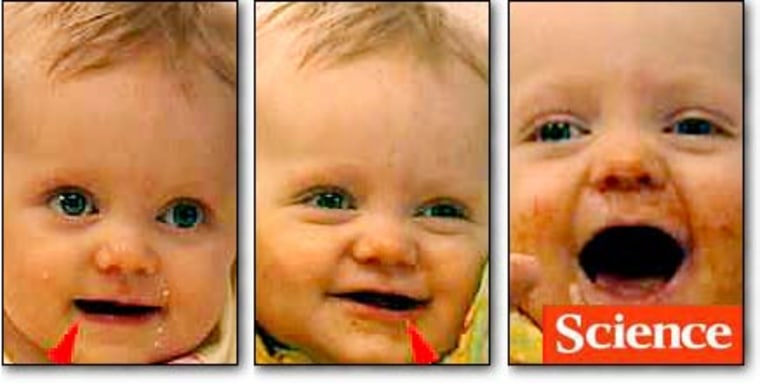

Petitto and Holowka decided to try this approach on infants. They videotaped five babies with English-speaking parents, and five with French-speaking parents, recording three different types of mouth activity.

“Babbles” were vocalizations with sounds found in spoken language, having repeated syllables, and lacking obvious meaning or reference. “Non-babbles” were vocalizations missing any of these three criteria, such as sounds like the playful “aaahh.” Smiles made up the third category.

Two coders, who knew how to measure mouth shapes according to the laterality index, but did not know what the research was about, watched the video clips frame by frame, and rated the lopsidedness of the babies’ mouths.

“Our hypothesis was, that if babbling is just the baby getting control of the mouth, and all early vocal behaviors are equally non-linguistic, then you wouldn’t expect to see any differences whether the baby is smiling, or yawning, or crying, or producing those endearing repetitive little bundles of sound, such as ‘dadada,’ which we all know as babbles,” said Petitto. “But that’s not what we found.”

Instead, the results showed that the babies’ mouths opened wider on the right side during babbles, on the left side during smiles, and were symmetrical during non-babbles. Thus, the researchers concluded, the language-control center of the brain was active during babbling only. The results also suggested that the emotion-control center of the brain, which is on the right side of the brain, may be engaged during smiles, when the left side of the mouth opens wider.

“Our findings establish that the linguistic centers are online early, and that babbling is a fundamentally linguistic activity,” Petitto said.

Parenting possibilities

The Science authors are optimistic that their method might also be useful for identifying babies that may later develop language disorders. These babies may not have such asymmetric mouths when babbling, Petitto said. If it works, this method could alert parents to potential problems well before the child has spoken his or her first word.

Although the study reveals a link between babbling and language, it doesn’t offer parents any way to tell precisely when their darlings may utter their first words. The gap between when a baby first babbles and produces its first words typically varies anywhere from two to five months. But the good news is that once babbling begins in earnest, the first word is not too far off, according to Petitto.