After working for the city of Zanesville, Ohio, for 27 years, Sharon Newton had to go back to school.

Newton lost her job this year, and when she went to look for a new one she discovered that, even with all of her experience, she wasn’t prepared for the modern work force. When prospective employers asked about her computer skills, she had no answer.

It turns out “that is extremely important,” said Newton, who needed help with using spreadsheets and other entry-level office computer tasks. She is now enrolled in computer training courses offered by Zane State University and by Experience Works, a nonprofit national job training organization.

Vicki Bateman, the director of Experience Works in Zanesville, said the classes taught “very basic computer skills,” beginning with “how to turn on the computer.”

“They learn a little bit of Word,” Bateman said. “They learn a little bit of the Internet.”

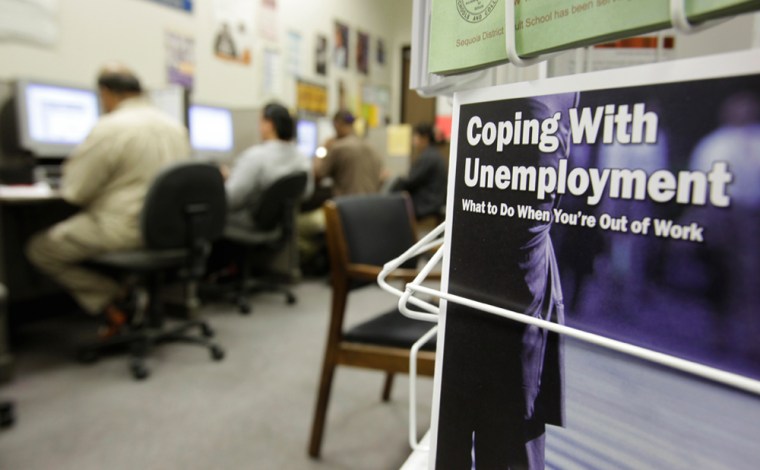

A digital divide in the hiring office

However deeply computers may have embedded themselves into modern life, there are still millions of people for whom they remain a challenge. For these Americans, finding a new job during a time of high unemployment can be especially difficult.

No one knows how many they are, because there is almost no credible research to assess Americans’ overall computer skills. Economists at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology’s Sloan School of Management, who highlighted the lack of data, lamented recently that researchers have, at best, “only cloudy information on technology use” and “levels and kinds of job skill requirements.”

That means it’s impossible to quantify the impact of computer literacy on unemployment. But related research and anecdotal evidence suggest a significant link.

About a fifth of Americans don’t have Internet access at home, the Pew Internet & American Life Project reported in June. Their profile — generally older and less educated — correlates closely with the demographics of those suffering the fastest rises in unemployment, an analysis of data from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics shows.

For them, the first obstacles are the keyboard and the mouse.

“Some people do not own computers, and others do not have the computer skills to complete online job applications,” said Benita Ugoline, director of the Greater Kansas City Urban League’s Career Marketplace, which drew more than 1,000 unemployed workers to its annual job fair this year.

Traffic from job-seekers has been heavy on computers at the Pierre Moran branch of the Elkhart Public Library in Elkhart, Ind., where msnbc.com is reporting on one of the areas hardest-hit by the economic recession. The library opened an hour early last Sunday to handle the rush, and Sasha Garcia, a staff member with the state’s WorkOne jobs program, was on hand to help navigate the computer system.

Most of the problems that arise with the computers are very basic, said Garcia, who patiently showed users how to use the mouse and pressed the key to unlock the capital letter setting.

Garcia told The Elkhart Truth, msnbc.com’s partner in the Elkhart Project, that whenever she suggested enrolling in a computer skills class, workers often brushed her aside and told her they didn’t have time right now.

“I tell them unemployment [benefits are] not going to last forever,” Garcia said. “They should try to get help.”

First step: How do I use e-mail?

As states lay off their own workers — including clerks and administrators at unemployment offices — they are increasingly funneling the jobless to online government portals like WorkOne to file for benefits. That can aggravate the problem.

When officials in Oahu, Hawaii, projected the local unemployment picture through June, they undertook an assessment of the state’s online jobs network. What they found was startling: Fully 60 percent of job-seekers “do not have adequate computer skills or access to the Internet and have difficulty in navigating HireNet Hawaii on their own.”

When officials in Indiana assessed online unemployment filings at public libraries — where many lower-income Americans go to access the Internet — they discovered that the “customer-based self-service approach often resulted in inaccurate information or required staff assistance.”

Bateman, of Experience Works in Ohio, said many job-seekers’ computer literacy fell well short of what government agencies assumed when they tried to direct users to online systems.

Often, counselors have to start by setting users up “with an e-mail address that they can actually attach to their résumé [to] send it out to an employer,” she said, because it was “something that they did not know when they first walked in the door.”

Older workers face many obstacles

Among those hardest hit by the demand for computer skills are older workers, for whom unemployment rates are at 60-year highs, having more than doubled since the recession began in December 2007. Just three years ago, an unemployed worker 55 or older could expect to spend six weeks finding a new job, the Labor Department reported; this summer, that had lenghtened to 30 weeks.

In May, New Mexico officials opened employment skills centers specifically for those 50 and older. While older job-seekers are considered more reliable and motivated than their younger competitors, “many lack computer sophistication and job-seeking skills,” said Cindy Padilla, head of the state’s Department of Aging and Long-Term Services.

The challenges are multiple, according to research by the American Medical Informatics Association, the professional organization for specialists in the use of information in health care. Besides being less likely to have kept up to date on the latest software, older workers also face physical limitations, such as failing memory, trouble reading small typefaces used in common interfaces and difficulty using a mouse.

There are also technology-driven roadblocks to communication, said Sandy Capps, director of training and development for American Behavioral of Birmingham, Ala., which manages human resources services for corporations.

Many older workers “prefer meeting face to face and talking about issues,” Capps said, which can cause friction with younger hiring officers and managers who “prefer to e-mail and text.”

That contributes to a perception that older job-seekers are “slow” and “unable to handle technology, she said, “and in the workplace, that can cause some problems.”

Such obstacles mean programs like Experience Works are vital to many in the job market, said Dorothy Rudysill, who entered the organization’s training programs after she retired at 65 and moved to Manistee, Mich., four years ago. She ended up working part-time at Love Inc., a nonprofit social services group.

Without help from Experience Works, “I honestly don’t think I would” have been able to re-enter the workforce, Rudysill said. “I think I would have been more discouraged, and I think I would have quit and just tried to get by.”