More than a century after Billy the Kid’s heyday, the Old West outlaw is still stirring up trouble. But this time, the showdown pits mayors against sheriffs, and forensic science against the uncertainties of the grave. Could DNA testing resolve once and for all who lies buried beneath the Kid’s New Mexico headstone, or would it merely cast fresh doubt on a 122-year-old legend?

At first blush, the saga sounds like a straightforward detective story: Tradition says that Billy the Kid (a.k.a. William H. Bonney, Henry McCarty, Kid Antrim) was killed by Sheriff Pat Garrett back in 1881 and buried in Fort Sumner, N.M. But in 1950, a Texas man named “Brushy Bill” Roberts claimed that he was the real Billy the Kid and that someone else had been shot in his place. He said he had lived incognito for decades but was finally seeking pardon for his crimes. Roberts died later that year, and is now buried in Hamilton, Texas.

As if that weren’t complicated enough, there was yet another claimant to the infamous name: John Miller, who died in 1937 and is buried in Prescott, Ariz.

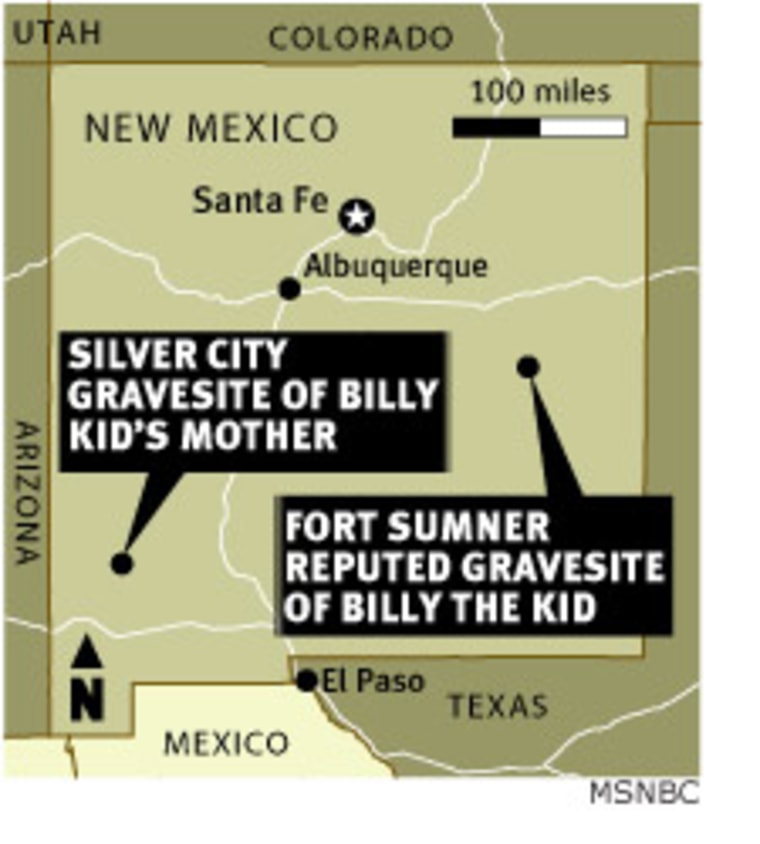

So which story is correct? Back in June, two New Mexico sheriffs and the mayor of Capitan, N.M., proposed a 21st-century solution: Exhume the remains from all three gravesites, and match the DNA against a sample taken from the body of Billy the Kid’s mother, Catherine Antrim, who is buried in Silver City, N.M. The results would confirm one of the stories, or at least disprove the impostors’ claims.

“This part of our history is something that we need to prove and stand on,” said Gary Graves, the sheriff of De Baca County, which encompasses Fort Sumner. “Other people in other states have done this with Jesse James. They want to prove their history. And if history has to change, so be it.”

But it turns out that the mystery of Billy the Kid isn’t that simple: Rather, it touches upon the twists and turns of Old West history as well as the politics and economics of the New West.

Graves, along with Lincoln County Sheriff Tom Sullivan and Capitan Mayor Steve Sederwall, has petitioned New Mexico’s 6th District Court for an injunction allowing them to exhume Catherine Antrim’s remains and extract a tissue sample for DNA testing. They say the only reputed heir of Billy the Kid, self-proclaimed great-grandson Elbert Garcia, supports the request. Graves has even opened an official homicide investigation file on the death of Billy the Kid (case No. 03-06-136-01, “opened 6/7/03”).

But the mayors of Fort Sumner and Silver City say they won’t let the bodies buried in their towns be disturbed, and that sets the stage for a legal showdown this winter in New Mexico’s 6th District Court. One hearing, scheduled in December, is to determine whether Silver City’s mayor has legal standing in the matter of Catherine Antrim’s remains, said Sherry Tippett, the attorney representing Graves and his fellow petitioners. The key hearing on the exhumation is due in January.

Both sides say they’ll appeal if the court rulings don’t go their way.

“We’ll go as far as we can go with it,” Fort Sumner Mayor Raymond Lopez told MSNBC.com. “I’ve got attorneys coming out of the woodwork on a pro bono basis.”

Politics and the kid

Why wouldn’t Lopez and his counterpart in Silver City, Terry Fortenberry, want to have the tests done, particularly if the results could well back the mainstream view that Billy the Kid was indeed killed and buried in their locale? That’s what De Baca County Sheriff Graves, who works in Fort Sumner, is wondering.

“This is a very, very hot issue, in which New Mexico is losing a lot of tax dollars, tourist income,” the sheriff said. “Why are we throwing it away? You take a small town such as Fort Sumner — we are very, very, very dependent upon our tourism base.”

By solidifying its claim on the Billy the Kid story, Fort Sumner and New Mexico could give their tourism trade a boost, Graves said. That angle is one reason why New Mexico Gov. Bill Richardson supports the use of DNA analysis to solve the mystery.

“We want to get to the bottom of it,” Richardson said in a Voice of America report. “And if it means New Mexico gets a little attention, so be it. I’m the governor, I want to see promotion, I want to see tourism go up. I want to see people fascinated by Billy the Kid. And that means a fascination with New Mexico.”

Lopez and other opponents of the testing, however, say there’s more to be lost than to be gained.

“This is an industry for us,” Lopez said. “It’s no different from Intel, or Sandia Labs, or Kirtland Air Force Base. It’s that big for us. We don’t have much to live off of other than the legend, so we have to protect it.”

Science and the kid

Theoretically, DNA testing could indeed show which individuals are related to each other, and which are not, all on the basis of samples taken from remains. The tests proposed for Antrim and her purported progeny would analyze mitochondrial DNA, which is passed down virtually intact from a mother to her children. If you can assume that the samples were collected from the right remains, today’s genetic tools could identify even century-old remains, as they did in the case of Russia’s last czar and his family.

The problem is, how do you know that you’ve got the right remains?

“I have no problem with the DNA bit,” said El Paso historian Leon Metz, who wrote a biography of Sheriff Pat Garrett. “The only thing that worries me is that I have been to Catherine’s grave, and she has a nice marker on her grave, and I assume that’s her grave — but is it?”

Over the decades, remains have been moved and gravestones have been shuffled to such an extent that it’s not crystal-clear that Antrim is buried precisely where her markers now stands. Metz said the same goes for Billy the Kid: “We know where the stone is, but we don’t know if he’s under it.”

So what happens if the wrong remains are retrieved and tested?

“Guess what happens?” Fort Sumner Mayor Lopez asked. “Sixty miles from Fort Sumner, someone else is going to say, ‘Well, Billy the Kid was buried here.’ And 60 miles from there, someone will say, ‘He’s buried here.’ ... There’s nothing good that can come out of this.”

Lopez said he’s already satisfied with the evidence backing Fort Sumner’s claim, and contends that most of the town is with him on this: “If anybody else wants to say they have Billy the Kid, that’s fine — let them prove it.”

The mayor has complained that Sheriff Graves was wasting public resources on a publicity stunt for other personal gain. But Graves said he’s not making a dime on the venture, and insisted that no public funds were being used.

“Every dollar that has been spent on this has been either private money or out of our own pocket,” he said.

The sheriff said there was too much at stake not to do the testing.

“I don’t believe that we’re the only town in the world, and the world is very interested in this,” he said. “People want the truth, people don’t want a lie. If Billy the Kid is not here, they want to know that.”

History and the kid

The DNA controversy does indeed go beyond De Baca County, N.M.: A grass-roots group called the Billy the Kid Historic Preservation Society is helping to organize opposition to the exhumations.

“We get e-mail almost every day: people from Brazil, Argentina, throughout the United States,” Trisha Saunders, one of the group’s co-founders, told MSNBC.com. “They all say the same thing: We come to see gravesites that are undisturbed, we don’t want to see sites that are pulled apart.”

Saunders, who lives in Seattle, said she became involved in the controversy because she was enthralled by the unspoiled charms of the Old West and worried that the campaign to dig up the old cemeteries would backfire.

“We’ve really only heard the tourism/boosterism aspects of this whole procedure,” She said. “The consequences will be really severe. I think, rather than having a positive effect on tourism there, it’s having just the opposite: It’s really devastating the economy of those small towns, and really cheapening the historical authenticity of those small villages and cemeteries.”

Graves sees it differently: “When we’re dead and gone, all that’s left is a shell,” he said. “I believe if Miss Antrim were alive, she would state, ‘I’ll gladly donate my DNA because I want you to prove that that is my son.’”

But lacking a pronouncement from the grave, the showdown over Billy the Kid won’t be over soon. And maybe that’s not such a bad thing.

“However it comes out, it keeps the legend alive,” Metz said.