Trucker Bob Caffee needed a medical card fast. His certificate from the U.S. Department of Transportation was to expire in two days, and he was in Southern California, halfway across the country from his regular doctor. So Caffee headed to one of the medical clinics that have sprung up at truck stops across America.

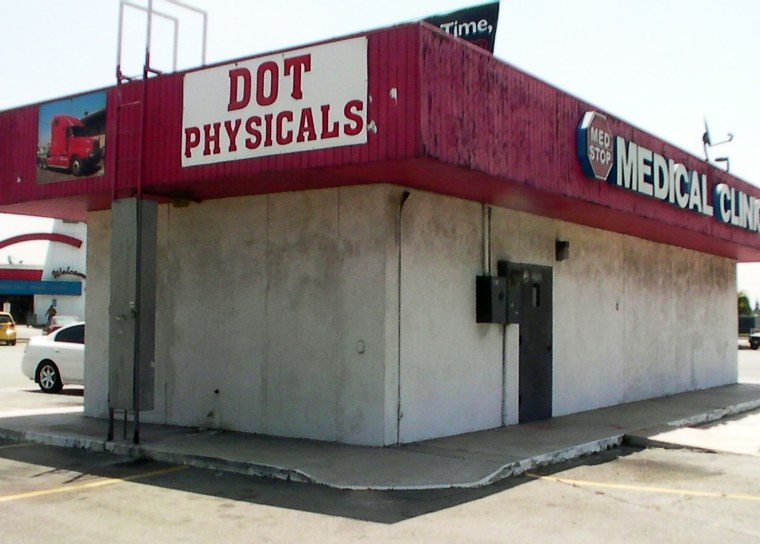

The clinic in Ontario, Calif., where Caffee stopped, is housed in a small, rundown building next to a Travel Centers of America truck stop. A sign advertises "DOT Physicals" next to a picture of a red truck.

"You say, 'I need a DOT physical,'" and the assistant says, "'OK, come back here and I’ll call the doctor,'" Caffee said.

The two of them checked his blood pressure, urine, breathing, hearing and vision. Caffee remembers that he had trouble reading past the top two lines of the eye chart. "I told her I wear glasses, and she OK'd me," he said, even though his driver's license didn’t say he was required to wear glasses.

The whole thing was over in 20 minutes, and Caffee emerged with a medical certificate that states he is healthy enough to drive a commercial truck for the next two years. Cost of exam: $30.

The exam Caffee underwent is required for all interstate commercial drivers. However, in many states, almost any health professional — including MDs, osteopathic physicians, chiropractors, physician assistants and advance practice nurses — can issue medical certificates for truck drivers. There are no training requirements and only minimal standards for what to check.

If a trucker is denied by one examiner, he can easily try another. There is no database to check whether medical certificates are valid, or whether a driver is "doctor shopping."

Drivers can download a medical certificate from the Internet and fill it out themselves. Others don’t bother getting a medical certificate — genuine or false. Few are ever caught. A trucker caught without a certificate is often given a fine — and allowed to drive on.

Deadly consequences

The problem of medically unqualified commercial drivers first drew national attention in 1999 when a bus driver veered off Interstate 610 near New Orleans, struck a guardrail, went through a chain-link fence, vaulted over a golf cart path and rammed into a dirt embankment, killing 22 of the 43 passengers on board.

The driver, who had a current medical certificate, had been in and out of the hospital the day before for treatment of his kidneys. He was released less than eight hours before reporting to work, according to an NTSB . Post-accident tests were positive for marijuana and an over-the-counter sleep medication that can cause drowsiness and dizziness. A passenger reported seeing the driver "slouch down" prior to the accident.

The accident prompted the National Transportation Safety Board to issue a series of stern recommendations in 2002 to the Federal Motor Carrier Safety Administration, whose primary mission is to prevent commercial motor vehicle-related fatalities and injuries.

Specifically, the board directed the FMCSA, part of the Department of Transportation, to "prevent medically unqualified drivers from operating commercial vehicles" and "establish a medical oversight program for all interstate commercial drivers."

Mitch Garber, a NTSB medical officer, said the FMCSA’s response to the board’s calls for tougher medical standards has been disappointing. The agency has addressed a few problems, but the approach has been piecemeal and largely ineffective, he said.

"It’s no more difficult for a medically unqualified driver to drive today than when the recommendation was made," Garber said.

From 2002, when the recommendations were made, through 2008, the last year for which data is available, there were at least 826 fatal crashes involving medically unqualified or fatigued drivers, according to a News21 analysis of the FMCSA Crash Statistics database. News21, a college journalism coalition, joined with the Center for Public Integrity, a nonprofit investigative journalism organization, to work on the analysis. Many of their stories are being published this week by msnbc.com.

Fatigued drivers are included in the analysis because sleep apnea, a sleep disorder that interrupts breathing, is a common problem for commercial drivers. An estimated 36 percent of commercial drivers have the condition, according to the FMCSA. The agency encourages medical examiners to screen for sleep disorders, and drivers with such disorders can be disqualified, but there are no strict requirements.

The fatal accidents included:

- A 2007 incident in Kansas in which a truck crossed a median on Interstate 135 and collided with an SUV carrying two women and their infants. One woman and her 10-month-old son were killed. The truck driver had been diagnosed with sleep apnea and was given a provisional medical card. When the card expired, he went to a different doctor and got fully certified, according to Amy Hanley, an assistant district attorney in Saline County, where the accident occurred.

- In 2004, a truck veered into the left lane of Texas Highway 75, crossed the median and flew into the air, crashing into oncoming traffic. The truck hit an SUV carrying a family and a truck carrying roofers, killing 10 people. When police searched the driver’s briefcase they found three prescription medications issued to him while he was in Poland earlier that year, according to an NTSB . The trucker said he had been taking medication for depression but had stopped because it made him drowsy. Less than five weeks earlier, he had an exam and was issued a medical certificate.

- In 2000, a trucker on Interstate 40 in Tennessee collided with a state highway patrol vehicle, killing a state trooper. The truck then went across the median and hit a Chevy Blazer heading in the opposite direction, seriously injuring that driver. The trucker had been diagnosed with obstructive sleep apnea and underwent surgery to correct the problem but did not report either the diagnosis or the surgery during his medical examination. An NTSB said the driver’s condition predisposed him to falling asleep behind the wheel. The investigation faulted the medical certification process for failing to detect the driver’s condition and allowing him to drive.

Rep. Jim Oberstar, D-Minn., said he is "very disappointed that FMCSA has allowed this situation to continue despite the overwhelming evidence that drivers are finding ways to circumvent the medical requirements for a Commercial Driver’s License." He said he plans to put it on the legislative agenda for next year.

Maggi Gunnels, the FMCSA director of medical programs, said the agency understands that a comprehensive system of monitoring and tracking medical certificates is needed.

But getting there, she said, is complicated.

How it works

Over the past five years, 902,416 citations have been issued to commercial drivers who can’t prove they’re medically qualified, according to a News21 analysis of the FMCSA Roadside Inspections Driver Violations database. That’s about 15 percent of the total violations issued at roadside checks.

Drivers who are caught using or in possession of drugs or alcohol are yanked off the road. The same is true for some — but not all — drivers who don’t have medical certificates.

Buses carrying passengers, for example, are pulled off the road if the driver doesn't have a medical card. Those drivers "cannot leave the scene until the situation is rectified," said Steve Keppler, interim executive director of the Commercial Vehicle Safety Association, a nonprofit organization that works on safety enforcement.

But the rules are different for truckers and others who don’t have passengers on board. While practices vary from state to state, truckers usually are issued citations and told to fix the problem at a later date. Then they’re allowed to drive off.

A trucker can pile up multiple tickets for the same violation and still be allowed to drive — at least until he goes to court, where a judge may decide to take him off the road.

Often, law enforcement officials have a hard time determining whether a medical card is valid. There is no central database of medical certifications. To check, an officer would have to call the doctor who issued the certificate. Since commercial drivers travel all over the country, often at night, it can be next to impossible to reach a doctor at the right time, said A.M. Azbill, an officer with the Arizona Department of Public Safety.

"A lot of it you have to take on faith," he said.

Open to abuse

Any licensed medical practitioner can perform the DOT medical exam. That could be a doctor of medicine or osteopathy, a physician assistant, a nurse practitioner, or a chiropractor.

In all, an estimated 400,000 medical practitioners can perform the exam for the more than 6 million commercial drivers, according to a 2008 FMCSA survey.

"To be honest, it's bogus," said Leo Gutierrez, a trucker from Moreno Valley, Calif. "You can go to any hospital or any mom-and-pop shop. If they really wanted to enforce it, half the guys wouldn’t be qualified.

"When they give an exam, I think sometimes they’re feeling sorry for us," he added. "I've been to the $185 places and the $25 places, and they all give me the card."

A trucker who wants to skirt the system altogether can go to the FMCSA website and download the Medical Examination Report for Commercial Driver Fitness Determination, a that includes a driver’s health history and his exam results. The Medical Examiner’s , which drivers are required to keep in their possession, is also available on the Internet.

Doctors or drivers also can create and use their own forms. The only way to track whose signature and information is on the form is to call the number listed. There is no easy way to check whether the signature or information is authentic.

Neither is there a registry to track who is giving the exams or what the results are. If one doctor fails a driver, that driver can go from doctor to doctor until he finds one who will certify him.

This kind of doctor shopping is common, said Dr. Gordon Zellers of Akron, Ohio, a physician who examines hundreds of commercial drivers each year. Zellers said he recently had to fail a trucker who had two tubes in his chest because of a breathing problem that could cause him to pass out while he’s driving.

"It blew the guy's mind. He'd been driving for years and had never found a doctor that knew that," Zeller said. "He told us right to our faces, 'Well, I'm going to go to someplace else' … and he'll do that. And there will be no way for the other doctor to check it. Once they know the system and go doctor shopping they can get around a lot of things."

The system has been so ripe for abuse that the House Committee on Transportation and Infrastructure launched an investigation in 2008 into medical certification of commercial drivers.

The House commissioned a Government Accountability Office , which found that about 4 percent, or 563,000, of all commercially licensed drivers were eligible for full disability benefits. It also found 15 cases of drivers who got medical certificates despite serious medical conditions, including a truck driver with an amputated leg who was deemed medically fit after he demonstrated his fitness by pushing his doctor around the room in a rolling chair, and a bus driver with a breathing disorder who said he "occasionally blacks out and forgets things."

Investigators working for the House committee also collected medical certificates during roadside inspections to see how many fraudulent medical cards they could find. They sent 614 cards to the doctors listed and determined that 7 percent were forged, according to a committee .

The committee’s conclusion: The FMCSA should do what the NTSB had been urging for years and create a central repository for medical examiners to report the results of their examinations.

Slow to respond

When the FMCSA has acted to address medical certification problems, it usually has been prompted by congressional action. Even then, it can take years to fix a problem.

In 1986, Congress required states to include medical certificates as part of their commercial driver’s license programs. In 1999, when nothing had been done, Congress charged the FMCSA with the job of making certain that drivers were medically certified before they got their licenses.

The FMCSA didn’t start working on a new until 2006. Two years later, the agency issued a proposal that requires drivers to provide a copy of their medical examination certificate to their state drivers' license agency. The new rule won’t take effect until Jan. 30, 2012, 26 years after Congress acted.

Gunnels, of the FMCSA, said the new rule will help combat fraud, because once the states have established electronic systems, enforcement officials can look up who issued medical cards and determine if cards are valid.

But the NTSB says that doesn't go far enough. Each state will keep its own data, and that might not include a complete examination form. Drivers, not doctors, are responsible for sending in data, which leaves the system open to abuse, critics say.

The FMCSA also has taken steps to create a of certified medical examiners. Medical professionals would be required to go through training and pass an exam before they can issue certificates to drivers. Gunnels said the rule should become final later this year or early next year.

But again, safety officials aren’t satisfied. The FMCSA is writing the curriculum for the training but letting the private sector handle everything else, including the selection of examiners and the training itself.

One point of contention has been whether chiropractors should be allowed to give the exam. The NTSB says only doctors who are trained in pharmacology and can prescribe drugs should be allowed to administer the exam. The FMCSA has said that all medical staff, including chiropractors, should be included.

But the real issue, according to NTSB officials, is that there is no comprehensive oversight system for medical certification of commercial drivers that will prevent doctor shopping and make sure medical examiners who conduct the exams are qualified to do so.

"The feeling at the board is not that there are flaws in the system. There is no functioning system in place," Garber said.

One doctor's solution

Dr. Richard O’Desky of Akron has given hundreds of physicals to truck drivers seeking medical certificates stating they’re fit to drive.

When he started doing the physicals regularly about five years ago, he noticed lots of problems. Sometimes information — especially expiration dates — on the medical cards drivers brought him had been crossed out or modified. O’Desky suspected the truckers had been driving with fraudulent cards.

"They can do anything they want because nobody cares," he said. "Nobody’s looking."

Sometimes he couldn’t read the cards because of all the coffee stains. Other times, a driver would claim to have lost his card.

"They game the system all the time," said O’Desky, 62, who specializes in occupational medicine. "It’s a bad system. That’s really the deal."

O’Desky set to work figuring out a way to track the exams he gave and limit the amount of fraud. In the process, he created an electronic monitoring system for his patients that is close to what the NTSB has been asking for since 2002.

He and his longtime accountant, Robert Fott, started with a simple spreadsheet to track exams. They developed a program and website where they can enter a driver’s information and produce a plastic medical card with the driver’s name, picture, address, signature, medical expiration date, and a bar code that can be scanned to pull up the driver’s medical information. The plastic cards are not only more durable, they can’t be easily duplicated.

O’Desky said that once the cards were in drivers’ hands, calls started coming in from confused law enforcement officers who were used to seeing the paper cards that anyone can download from the FMCSA site.

O’Desky expected those calls; what he didn’t expect was a letter from Congress.

In 2008, the House Committee on Transportation and Infrastructure started investigating the medical certification program. Staff collected 614 cards from drivers at roadside checkpoints and sent copies to the examiners listed. O’Desky was one of them. He responded right away, and his comment that "forgery is so commonplace, no one gets alarmed about it anymore" appeared in the committee’s report.

A year later, O’Desky was meeting with congressional representatives, the FMCSA, and anyone else who would listen to him. Staffers from the offices of Rep. Betty Sutton, D-Ohio, and Rep. Steven C. LaTourette, R-Ohio, came to see his operation firsthand.

"We've paraded this in front of more people than I’d care to mention," O’Desky said. "Everyone says, 'Great job,' but in terms of advocacy we've yet to find someone to pick up a flag and say, 'This makes sense.'"

When asked about O’Desky’s program, Maggi Gunnels, director of medical programs for the FMCSA, said, "We really value and appreciate these efforts as long as they meet the minimum data elements." However, she said, the FMCSA will have its own system in place before long.

Part one: Driving While Tired: Safety officials are slow to react

Sidebar: Shhhh! Your pilot is napping

Part two: Video in the cockpit: Privacy vs. safety