The cliche notwithstanding, there are atheists in foxholes.

In fact, atheists, agnostics, humanists and other assorted skeptics from the Army's Fort Bragg have formed an organization in a pioneering effort to win recognition and ensure fair treatment for nonbelievers in the overwhelmingly Christian U.S. military.

"We exist, we're here, we're normal," said Sgt. Justin Griffith, chief organizer of Military Atheists and Secular Humanists, or MASH. "We're also in foxholes. That's a big one, right there."

For now, the group meets regularly in homes and bars outside of Fort Bragg, one of the biggest military bases in the country. But it is going through the long bureaucratic process to win official recognition from the Army as a distinct "faith" group.

That would enable it to meet on base, advertise its gatherings and, members say, serve more effectively as a haven for like-minded soldiers.

"People look at you differently if you say you're an atheist in the Army," said Lt. Samantha Nicoll, a West Point graduate who in January attended her first meeting of MASH. "That's extremely taboo. I get a lot of questions if I let it slip in conversation."

The decision on recognition goes first to an Army agency called the Installation Management Command and may be reviewed after that by the Army Chaplain Corps. Neither agency returned calls for comment.

Other U.S. military bases look on

MASH members said chaplains at Fort Bragg have been supportive of their effort.

Similar groups of non-theists at about 20 U.S. military bases around the world are watching the outcome at Fort Bragg in hopes it will lead to their recognition, too, said Jason Torpy, president of the Military Association of Atheists and Freethinkers.

MASH, whose name conjures the 1970s movie and sitcom about an Army field hospital in the Korean War, formed in January, partly in reaction to a concert called Rock the Fort that was sponsored by an evangelical Christian organization and held on base last fall.

Griffith, an atheist when he joined the Army 4 1/2 years ago, said he tried to organize an atheist festival but called it off because higher-ups were not providing the same support they had for the Christian event — a claim Fort Bragg officials deny.

Griffith said MASH has about 65 members among more than 57,000 active service members who live on and off the post. Bragg is the home of the 82nd Airborne Division and headquarters of the Army's Green Berets.

Fort Bragg Garrison Commander Col. Stephen Sicinski disputed Griffith's account of how the atheist concert came to be canceled but said the post is doing what it can to help Griffith win recognition for MASH. "He knows the procedures, he knows what the paper trail needs to look like, and we're guiding him along in the process to see where that goes," Sicinski said.

'Coming out of the atheist closet'

Meetings of military personnel who are non-theists — an umbrella term for the many varieties of nonbelievers — have been held at MacDill Air Force Base in Florida and aboard the aircraft carrier USS Abraham Lincoln. But groups of any kind are prohibited from meeting on Army bases without official recognition.

If the Fort Bragg group succeeds, it will be overseen by the Chaplain Corps. That might seem contradictory for a group defined by its lack of belief, but it means MASH's literature would be available along with Bibles and Qurans. It could raise funds on base and, its members say, they could feel more comfortable approaching chaplains for help with personal problems. Recognition would also be an official sign that not believing in God is acceptable, something members say is lacking now.

"They call it 'coming out of the atheist closet,'" Griffith said. "There are people who won't say anything to anyone outside of their own close-knit group. They don't want Grandma to find out, or whoever. People feel like they have to lie about it."

Griffith said he doesn't know of any soldiers being denied promotions because of their atheism, and he and other MASH members at Fort Bragg said they have no horror stories about outright discrimination, that the reaction from their comrades has amounted to little more than raised eyebrows and lots of questions.

Instead, they said, they are largely motivated by a sense of isolation and a desire to spend time with people who not only understand the military experience but also share their views on religion.

Looking for a 'close-knit community'

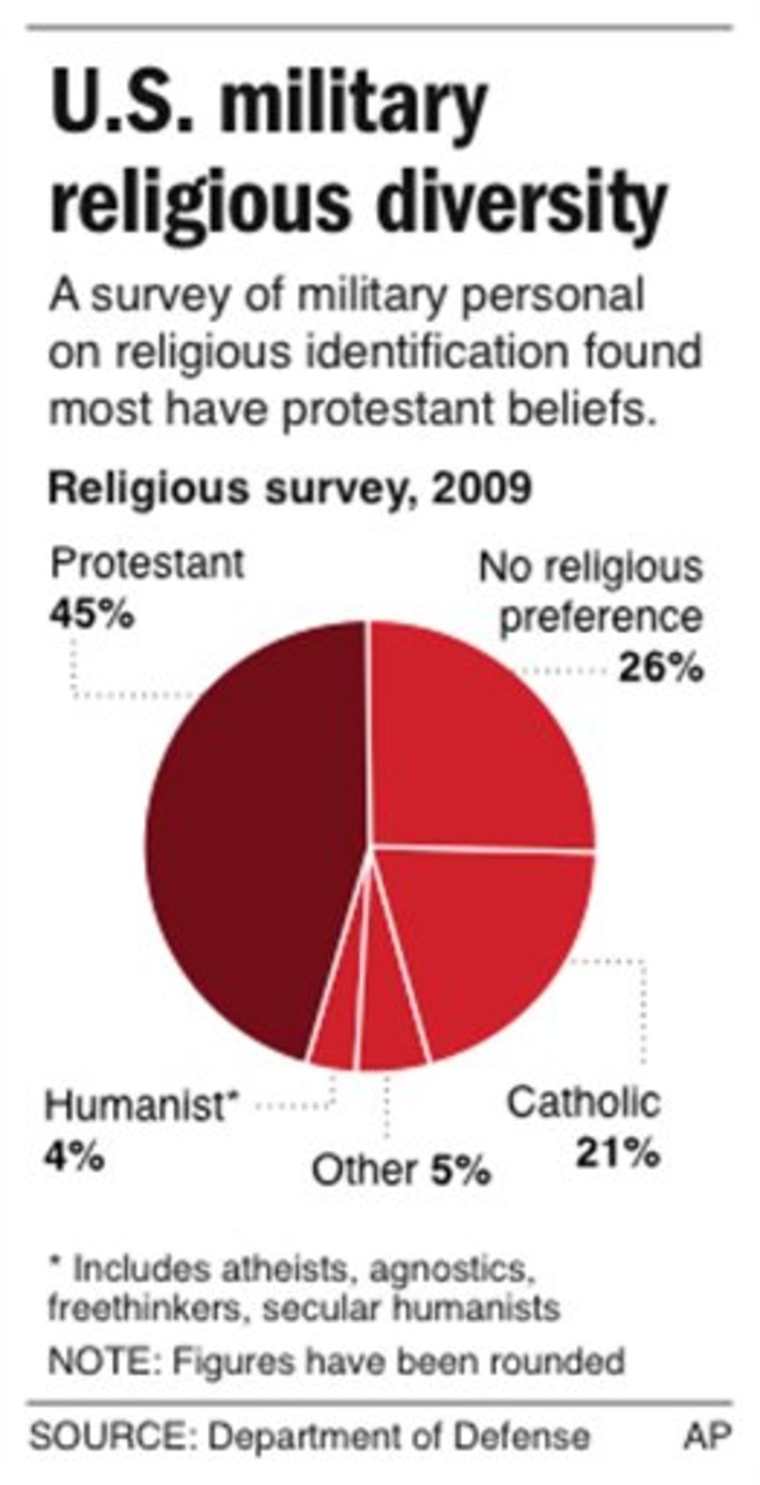

It is difficult to pin down how many nonbelievers are in the military, in part because some soldiers lose their faith or convert to a different one. But a report last June by the Pentagon's Military Leadership Diversity Commission concluded that about 20 to 25 percent of military personnel have no religious preference. Up to 3.6 percent identify themselves as humanist — a catchall that can refer to a nonreligious ethical philosophy.

Surveys of the general population generally find the "no preference" category at between 10 and 15 percent, a figure that has grown steadily over the past 20 years, making the military numbers less surprising, said Phil Zuckerman, a sociology professor at Pitzer College in Claremont, Calif.

"People are increasingly much more likely to identify themselves with no particular religion, although that doesn't mean they're atheists. About half the nonreligious are still believers," Zuckerman said.

The Pentagon is studying religious diversity in part to make sure tensions in society at large don't become problems in the military.

The MASH group meets at restaurants and homes, discussing books or having dinner together. About 15 people attend regularly, but Griffith said he has received inquiries from roughly 100 soldiers at Fort Bragg, along with dozens from other bases.

"Granted, most soldiers are Christian, but I'd like to see some secular kind of spiritual and emotional support," said Sgt. Adam Jennings, a Special Forces medic who has been in the Army for 11 years and served in combat in Afghanistan. "I want a place where I can go and be part of a close-knit community."