The hunt for some form of life elsewhere in our universe may spur a veritable fleet of robot orbiters, landers and rovers to study the surface of Mars in the coming years. But they might look in the wrong place.

Instead of probing for signs of alien life on Mars’ harsh surface, some researchers have suggested looking inside the planet, where there is mounting evidence of water ice near the equator and the potential for underground aquifers that could support basic, microbial organisms.

Spirit and Opportunity, the two robots currently exploring the Red Planet under NASA’s Mars Exploration Rover mission, have proved that water shaped the development of rocks on the planet’s surface. Meanwhile, Europe’s Mars Express spacecraft, now orbiting the planet, is preparing to unfurl a radar instrument that researchers say might find pockets of liquid water in subsurface caves or voids.

"We now know that big areas on the planet were made of soluble rock," Steven Squyres, a Cornell University astronomer and the science team leader for NASA’s Mars rover mission, said in an interview. "So if there’s rock that can be dissolved by water, the idea of such a cave is perfectly sensible."

Recent reports by U.S. and European researchers have hinted at connections between the presence of methane and other gases in Mars’ atmosphere and the possibility of water-harboring subsurface caves capable of sustaining life.

The theory is similar to actual conditions found in deep caverns on Earth, such as the Lechuguilla cave in New Mexico — the deepest found in the continental U.S. — where hardy bacteria thrive in a pool of water and feed off gases. Below the surface of Idaho, creatures dubbed methanogens give off methane as waste while subsisting on hydrogen from rocks around underground springs.

The meaning of methane

But whether some form of life once existed, or currently lives, in Martian caves is still unknown.

In March 2004, a trio of independent studies using Mars Express and ground telescopes announced the detection of methane in Mars’ atmosphere. Months later, in September, the European Space Agency released Mars Express data detailing an overlap of methane and water vapor concentrations.

Researchers stressed that a skeptical eye is required after news reports stating that some scientists had linked the presence of Mars methane to the possibility that microbial life may generating the gas as a byproduct of subsisting off underground caches of water.

"The fact that you find methane does not mean you have to have life," Tobias Owen, a University of Hawaii astronomer who was part of a team that detected Mars methane with ground-based telescopes, told reporters at a recent science symposium. "You have to be very careful."

Owen said that methane can be generated through the interaction of rock and water, where living creatures are not a factor.

While Squyres said he had not seen the recent news reports about the implications for Martian life — and does not know of any direct proof that life ever existed on the planet — he did say that in general, caves are not a prerequisite for subsurface organisms.

Life gets by on much less, housing-wise.

On Earth, Squyres said, there are many instances of life thriving in pore space and fractures underground.

Looking deeper

The search for liquid water — which some researchers have considered a prerequisite for life as we know it — on Mars continues in May of this year when Mars Express is expected to deploy its MARSIS instrument, a radar tool designed to probe below the planet’s surface.

From the surface, the Spirit and Opportunity rovers have not found any signs of caves during the exploration of their respective Mars landing sites, Squyres said.

"If there’s a water table down there, you might — might — be able to detect it with ground-penetrating radar," said Squyres, who is also a co-investigator with the Mars Express mission in addition to his work with the Mars rovers.

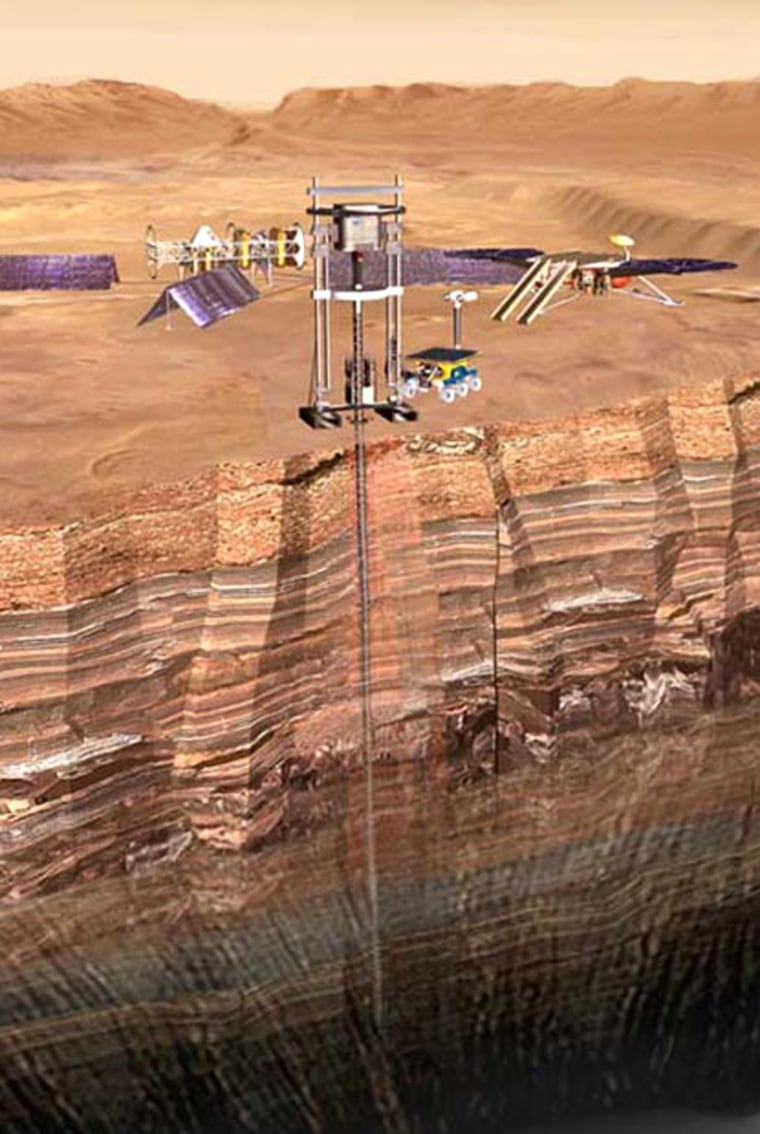

MARSIS, short for Mars Advanced Radar for Subsurface and Ionospheric Sounding, is a 130-foot (40-meter) boom designed to send out low-frequency radio waves to probe for underground water. ESA researchers have said they hope the instrument can reach down to 3 miles (5 kilometers) below the Martian surface.

"Nobody’s ever looked at Mars in this way before," Squyres said of the MARSIS plan. "Every time we look at Mars with some new technique something interesting tends to pop up, so I’m very excited to see what it’s going to show."

Safeguarding Mars

One of the dangers facing any mission aimed at seeking out signs of past or present life on Mars is the potential of contaminating the Red Planet env—ironment simply by being there.

"If you’re going to go to another world looking for life, you don’t want to take anything with you," John Rummel, NASA’s planetary protection officer, told Space.com.

Earlier this year during a science conference, Rummel discussed the challenges the science community may face in communicating the discovery of extraterrestrial life to the public, should researchers ever make such a historic find.

"We tend to be very careful and conservative," Rummel said. "Because you need to be sure of what you do know, what you don’t know and what you can only guess at."

In 1996, NASA and Stanford University researchers published findings in the journal Science that a meteorite from Mars found in Antarctica — contained possible evidence of past life on Mars. The space agency was very careful to include a scientist at the press conference who aired concerns about how the meteorite data was interpreted, Rummel recalls.

"It’s an art of managing uncertainty," Rummel said, adding that such processes are meant to keep NASA honest and accurate. "The public deserves an honest agency."