6 a.m. Your satellite-enabled alarm clock goes off.

Blame Albert Einstein for rousting you out of bed. Your clock sounds precisely at 6 a.m. because it’s one of those fancy digital models that is synchronized with the government’s atomic clocks and calibrated every second through the Global Positioning Satellite array circling the Earth. If they could not correct for the effects of relativity, Einstein’s most famous discovery, GPS signals would accumulate so many errors that their data would be meaningless.

6:15 a.m. You nick yourself shaving and drip toothpaste on your shirt.

Blame Einstein for the mess. His creation of a formula to measure the size of molecules dissolved in liquids made it possible for scientists — among many other, more important, leaps — to create or improve thousands of consumer products, including better shaving creams and toothpastes.

6:30 a.m. You click on the television to check the weather and traffic. It’s raining, and the traffic cameras show that the cars are already backed up for miles on the interstate. It’s going to be a rough commute.

Blame Einstein for your bad mood. His declaration of the photoelectric effect made possible the eventual invention of television cameras. And the remotes that control them. Also, it’s why digital cameras work.

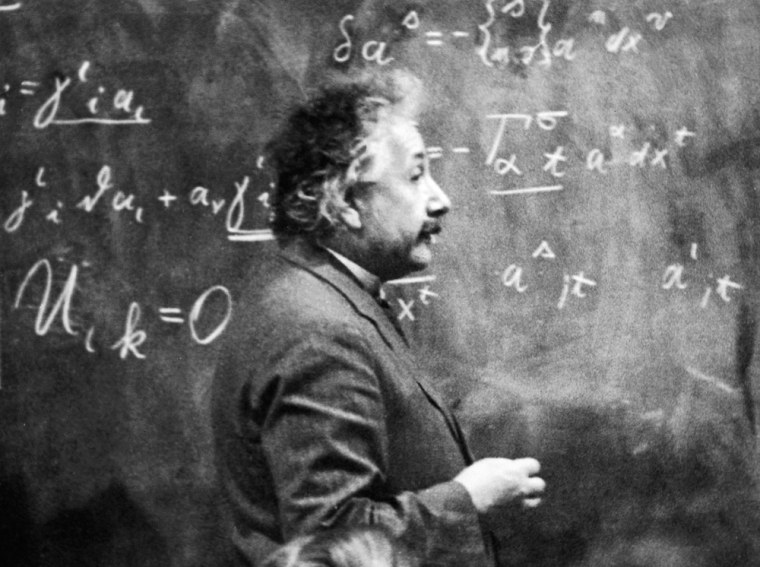

You’ve been up for just a half-hour, and already your day is being controlled by Albert Einstein.

“How do you explain it?” asked John Rigden, a physicist at Washington University in St. Louis and author of “Einstein 1905.” After all, when Time magazine named Einstein its Person of the Century, it chose him over “all of the other people that made their indelible mark on the 20th century, all of the practical people — [Bill] Gates, you could go on and on.”

The flash of inspiration

Most likely, we think of Einstein first as the man who paved the way to development of the atomic bomb. This is not the right way to look at him.

Michel Janssen, a science and technology historian at the University of Minnesota, points out that Einstein had virtually nothing to do with developing the bomb, which grew out of the work of more up-to-date physicists in the 1930s. Einstein, in fact, was refused security clearance to have any role in the Manhattan Project, said Janssen, who was trained as a physicist and edited the volumes of Einstein’s collected papers on relativity.

However, many of Einstein’s other theories, which began pouring out in a burst of incandescent creativity 100 years ago, turned physics and our understanding of the natural world on their heads, giving scientists the tools to mold almost every observable aspect of life as we live it in 2005.

Einstein’s work gave us much more than eventual perfection of television, remote controls and digital cameras. His postulation of the photon (a “particle” of light) and the photoelectric effect — which was described in his first great paper of 1905 and won him the Nobel Prize in 1921 — gave us scores of everyday applications.

Einstein’s identifying of photons underlay the development of many of the advanced electronic inventions of the 20th century. It was the statement of the quantum effect, without which we would not have cellular telephones or smoke detectors or burglar alarms or those doors that automatically open at the supermarket or on the elevator.

Indeed, you can argue that the entire field of computers and semiconductors owes its existence to Einstein’s paper of March 17, 1905. That’s why it’s pointless to speculate about what he might have accomplished had he been born 75 or 80 years later and therefore been able to use computers. Without his having done the work he did when he did it, we might not have computers today, or at least not in the form we recognize.

Albert who?

Moreover, it’s possible that in today’s scientific world, Einstein would have trouble getting his ideas heard.

Science today is an institutionalized pursuit, regimented by a hierarchy of credentials. What are your degrees? What university or research institute are you affiliated with? How much peer-reviewed research have you published? How much grant money can you command?

While Einstein’s work at the patent office in Bern, Switzerland, gave him wide opportunity to conduct sophisticated experiments on advanced submissions, he was, in his great year of 1905, still a 26-year-old government worker.

Recognizing ‘something profound’

“Would Einstein be able, in 2005, to become recognized as he did in 1905?” Rigden asked. “That’s a really open question.

“It’s not clear to me that he would be able to do that. If intelligent people really gave his manuscripts a careful read, they would have recognized something profound. He might be published, but boy, it’s not clear. He was fortunate to have lived when he did.”

Robert Schulmann, who co-edited Einstein’s collected papers and is former director of the Einstein Papers Project, is more hopeful that his voice would have broken through.

The journal that published his 1905 papers, Annalen der Physik, was the leading physics journal of the day. Among the editors who reviewed his submissions were Nobel laureate Wilhelm Roentgen, who discovered X-rays, and Max Planck, another Nobel winner, who came as close to matching Einstein in sheer brain power as anyone else ever did. If such esteemed editors found merit in the theories of the government clerk then, Schulmann said, it is likely that they would do so today.

But even Schulmann said it would be an iffy proposition. Much of Einstein’s work was multidisciplinary and abstract, while physics today is focused and empirical.

“The possibility of coming out of almost nowhere, for a number of reasons, wouldn’t work today because of the highly philosophical character of his work. The questions he asked himself ... deal with space and time, which are philosophical concepts,” said Schulmann, who is at work on a biography of Einstein.

Janssen said there was “something special about the age that Einstein was working where he was, in a way, the right man at the right time at the right place. Between 1900 and 1925, you saw this tremendous overhaul of physics, and it is hard to imagine that today we’re going to see an overhaul on that scale.”

You can’t take a step without smacking into Einstein

The paper on the photoelectric effect was just one of several that Einstein issued in 1905 that fundamentally altered how physicists look at the world. From the other papers came an almost equally wide range of modern applications:

- Compact disc and DVD players use lasers, which Einstein first theorized in 1917 in advancing his work on the photoelectric and photovoltaic effects. “We have lasers in every supermarket checkout lane,” Rigden said.

- Medical revolutions like the PET scan rest on positrons, described by science journalist Robert Matthews as “antimatter electrons,” whose existence was implied by special relativity and quantum theory. (Science fiction revolutions, too: Antimatter, in reaction with matter, is what makes the Enterprise jump into warp speed in the “Star Trek” universe.)

- Carbon dating. We can take a stab at measuring how old fossils are thanks to Einstein (E=mc2 shows that mass and energy are interconnected; by measuring the degradation of nuclei in atoms of organic materials, the theory goes, we can measure how long they’ve been degrading).

- And all those everyday consumer products, which owe their existence, in no small part, to manufacturing methods that wouldn’t work without Einstein’s enunciation of the atomic theory of matter. In essence, he proved that atoms exist.

Before Einstein’s paper of May 1905, “many reputable scientists didn’t believe in atoms,” Rigden said. “May 1905 put the last nail in the coffin [of atomism naysayers]. No longer could the reality of atoms be denied.

“The nucleus wasn’t even discovered until 1909, so Einstein’s prescience was off the charts.”

Most important, perhaps, was Einstein’s restoration of the belief in the power of reason and intellect. He gave science back its confidence.

“Before the First World War, there was still a lot of faith in rationality. The First World War smashed this faith in reason pretty irreparably,” Schulmann said. “And here you had a man detached from all of the events of the First World War, basically, who with a pencil and paper was able to explain the logical and rational way that the world and the universe worked.”

Rigden suggested that “the first contribution that Einstein made that dramatically affects our lives was that he did it with the power of his mind.”

Einstein “wasn’t blessed with experimental data — it was mostly abstract ideas,” he said. “That is a distinctive aspect of homo sapiens: We have a big brain. ...

“He is a standard because of what he did. And how he did it.”