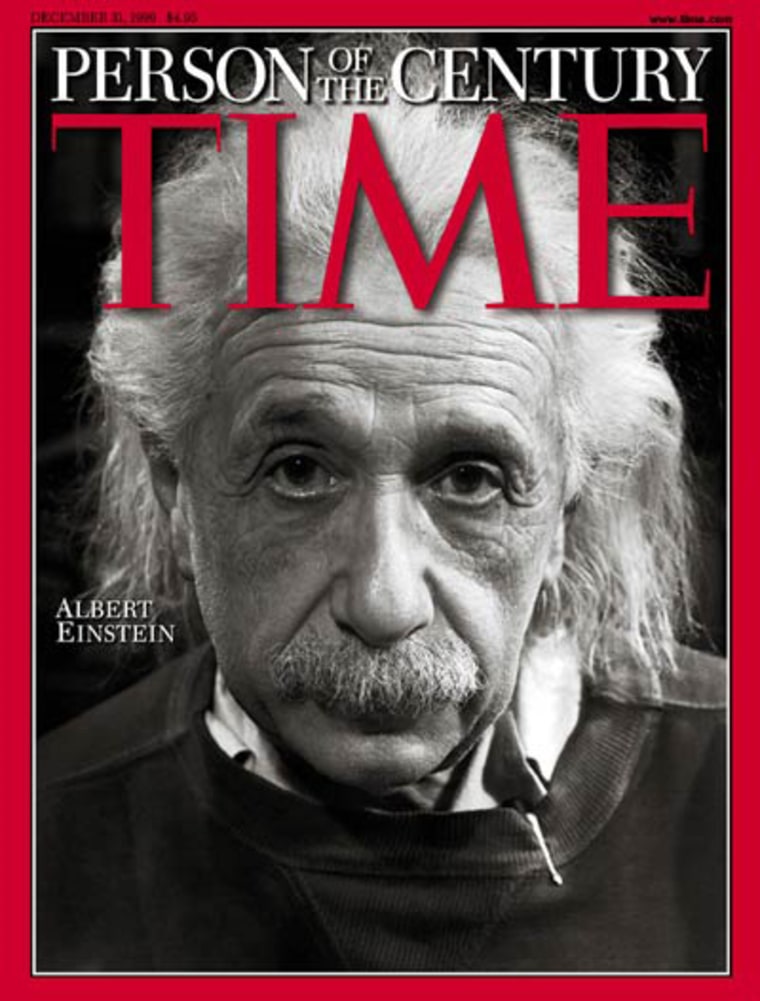

Albert Einstein’s impact on the world was so immense that any assessment must range beyond the sciences to take in the multifarious ways he changed culture.

It is a task made complicated by the myths and misunderstandings that encrust his reputation — as Einstein himself once said, “Everyone likes me, yet nobody understands me.” It is not for a lack of trying. Library shelves and Web search engine servers groan under the sheer weight of the data, true and false, amassed about Einstein and his life.

Einstein as outsider

The common story tells of how the lowly patent clerk went off by himself and, by the sheer power of his mind, came out of nowhere to shock the scientific world with the results of his “thought experiments” — products of a pure intellect undistracted by the demands of the academic world or the need to test his theories in the lab.

“The standard imagery for Einstein is the genius who fell from the sky or who’s walking down the street and bam, all of a sudden, is overwhelmed by this brilliant insight,” said Robert Schulmann, former director of the Einstein Papers Project and co-editor of his collected papers.

It is true that Einstein was a government functionary in Switzerland, while the intellectual nexus of science in 1905 was Germany. But his work at the patent office in Bern was of much greater importance than he has been popularly given credit for, affording him the opportunity to engage in sophisticated experiments in reviewing advanced ideas.

He was also classically trained, having earned his Ph.D. from the Swiss Federal Polytechnic School, and by 1909 he was well on his way to the top of the academic world, said Michel Janssen, a science and technology historian at the University of Minnesota and co-editor of the Cambridge Companion to Einstein.

Schulmann, who is working on a biography of Einstein, said: “Einstein worked for 10 years on what became, in 1905, the theory of special relativity. That is to say, he probably had the brilliant insight of simultaneity within six weeks of publishing it, as he says himself.

“But he has been mulling these problems and their connection with the question of corpuscular motion and Brownian motion and the light-quantum hypothesis — he’s been mulling these things for 10 years.”

Einstein as philosopher

The esteem Einstein earned in science meant that when he talked about the larger world, people listened.

Einstein began speaking out against war and violence before World War I, but after experiments during a solar eclipse proved general relativity in 1919 (“Einstein Theory Triumphs,” said a subheadline on the story in The New York Times), he became an overnight star.

As the “winner in this contest with Newton,” Schulmann said, Einstein was a media sensation. Front-page headlines followed him across America when he arrived for a tour in 1921, and his pronouncements on peace were already leading to his being seen as the “conscience of the world.”

Once he was compelled to abandon Germany during the rise of Hitler, Einstein emerged as a leading symbol of pacifism in the 20th century, held by some thinkers on a par with Mohandes K. Gandhi and Albert Schweitzer.

But Einstein’s commitment to pacifism was never absolute, as was publicly thought. In 1939, six months after the discovery of uranium fission, he began work on a letter urging President Franklin D. Roosevelt to build the atomic bomb, for fear that Germany would get there first.

“In view of this situation, you may think it desirable to have some permanent contact maintained between the Administration and the group of physicists working on chain reactions in America,” he wrote in August, going on to recommend specific sources of uranium ore in the former Czechoslovakia, Canada and the Belgian Congo.

Years later he called the entreaty the “one great mistake in my life” and said in a letter to President Harry S. Truman: “I know not with what weapons World War III will be fought, but World War IV will be fought with sticks and stones.”

Einstein as feminist target

Einstein is also at the center of one of the hotter debates to emerge from feminist theory. A wide range of scholars has suggested that his first wife, Mileva Maric, with whom he studied at the Polytechnic School, made equal or even greater contributions to his great 1905 papers but was denied credit.

Einstein’s letters to Maric include several references to “our work” and “our research,” and one biographer claimed to have seen an early draft of one the 1905 papers that was signed by both of them. Moreover, when Einstein won the Nobel Prize in 1921 — two years after they divorced, quite bitterly — he gave Maric the money.

The question is one that touches off heated arguments. In 1990, the dispute had become important enough that the American Association for the Advancement of Science convened a panel discussion, where scholars pursued what they saw as her vindication. A PBS documentary, “Einstein’s Wife,” made the case so compellingly that in an online poll on its Web site, 77 percent of respondents thought Maric “collaborated” with Einstein on the 1905 papers.

Editors of Einstein’s papers officially declared neutrality, but unofficially, Janssen and others say claims that Maric had much to do with Einstein’s greatest work were unfounded.

Often, feminist scholars “portray the editors of the Einstein Papers Project as a bunch of male chauvinist pigs who would not admit this even in the face of uncontrovertible evidence,” Janssen said. “The editors would be quite happy to acknowledge something like that. I, in particular, have written very unflattering things about Einstein, but for this particular proposition there’s just not a shred of evidence.”

Einstein and religion

Einstein’s famous rejection of the randomness inherent in quantum mechanics — “I cannot believe that God would choose to play dice with the universe” — was long ago appropriated by religious thinkers as proof that the world’s greatest scientist accepted the existence of God.

Einstein himself made it plain, however, that he did not. Such interpretations, he wrote in 1954, were “a lie which is being systematically repeated. I do not believe in a personal God and I have never denied this but have expressed it clearly.”

For Einstein, references to God were a convenient metaphor — easy-to-grasp shorthand, he wrote, for “the structure of the world so far as our science can reveal it.”

It is perhaps ironic, then, that Einstein’s theories contributed significantly to the revival of Christian fundamentalism in the last century.

Relativity theory implies that measurements, perceptions and observations long thought to be fixed really aren’t, a potentially mortal blow to belief in immutable truths based in natural law. Those truths would include religious accounts of creation and history, influencing some religious scholars and leaders to regard relativity as an attack on faith.

At its 1982 General Convention, the Episcopal Church noted that the “dogma” of creationism “has been discredited by scientific and theologic studies” — a contention rejected by Christian fundamentalists and one that is at the heart of Christian political movements to compel public schools to at least acknowledge the biblical account of creation.

“So where did moral relativism gain its footing in a nation founded on Judeo-Christian principles?” Kelly Hollowell of the fundamentalist Center for Reclaiming America wrote in 2004. “It actually started in the 1920s when a belief began to circulate in the U.S. that there were no longer any absolutes, specifically, of time and space, of good and evil, of knowledge and above all of human value.

“This belief system was built on the work of at least two prominent scientists: Albert Einstein and Charles Darwin.”

Einstein as charlatan

Here’s the ultimate proof of Einstein’s fame: There is a small but committed band of authors and bloggers dedicated to proving that relativity is wrong and that Einstein was a cheat.

In “Albert Einstein: The Incorrigible Plagiarist,” for example, Christopher Jon Bjerknes argues that Einstein stole all his ideas from earlier theorists, especially his first wife, while in “Proof of the Falsity of the Special Theory of Relativity,” Erik J. Lange puts forth, well, his proof of the falsity of the special theory of relativity.

There is, in fact, something of a publishing sub-industry specializing in books whose titles include variations of “the Einstein Myth” or “The Einstein Hoax,” dismissing relativity as, in essence, a religion.

But we already know what Einstein said about religion.