It was once dismissed by the White House as a third-rate burglary. And when it occurred, the story was assigned to a Washington Post police reporter, a rookie — Bob Woodward.

The date was June 17, 1972. On that fateful morning Woodward got a call from the desk. He went to the courthouse, expecting a routine police case.

"But it didn't smell routine when the five burglars walked into the courtroom in business suits," he says. "I've seen a lot of burglars. They normally don't wear business suits."

One of the burglars was James McCord.

Bob Woodward: The judge asked them, “Where do you guys work? Where do you come from?” No one would talk. And finally James McCord whispered something. The judge said, “Speak up.” And McCord said he had worked at the CIA. That was just like a 10,000 volt jolt.

Woodward instantly realized that lots of things about that burglary didn't add up. It happened at Democratic National Headquarters in the Watergate office complex. The five burglars not only wore business suits, they had electronic bugging equipment. And they carried cash — about $2,300 — some of it in sequentially numbered $100 bills.

But at the beginning, Woodward couldn't know that this burglary was part of a much larger scheme, organized in the White House itself: to destroy President Richard Nixon's enemies, real and imagined — the protesters against the Vietnam War, the press, not to mention the Democrats who opposed his re-election. All had been targeted for dirty tricks, wiretaps, and break-ins.

"The Nixon administration said, 'OK, we've got sort of a civil war going on here, and we're either going to win this war or lose this war.' And we had no intention of losing that war," says G. Gordon Liddy who worked for the president's re-election committee. Liddy went to prison for supervising the Watergate burglary.

But in June 1972, all that was a secret.

For reporters covering the Watergate burglary, there were a lot of questions, but not many answers. Why did two of the burglars carry address books bearing the name of Howard Hunt, a former CIA man who worked in the White House?

Woodward turned to a trusted source in a high place — a source he had been cultivating for two years, who demanded that he never be quoted or named.

Tom Brokaw: And what did he say?

Woodward: At first, he seemed very nervous, oddly enough. And he was not a nervous man. I said, “You know, anyone can have your name in their address book. What does it mean?” And he gave me the first key piece of information saying, “Don't worry. Howard Hunt is involved. And this is serious.” It was the first White House connection.

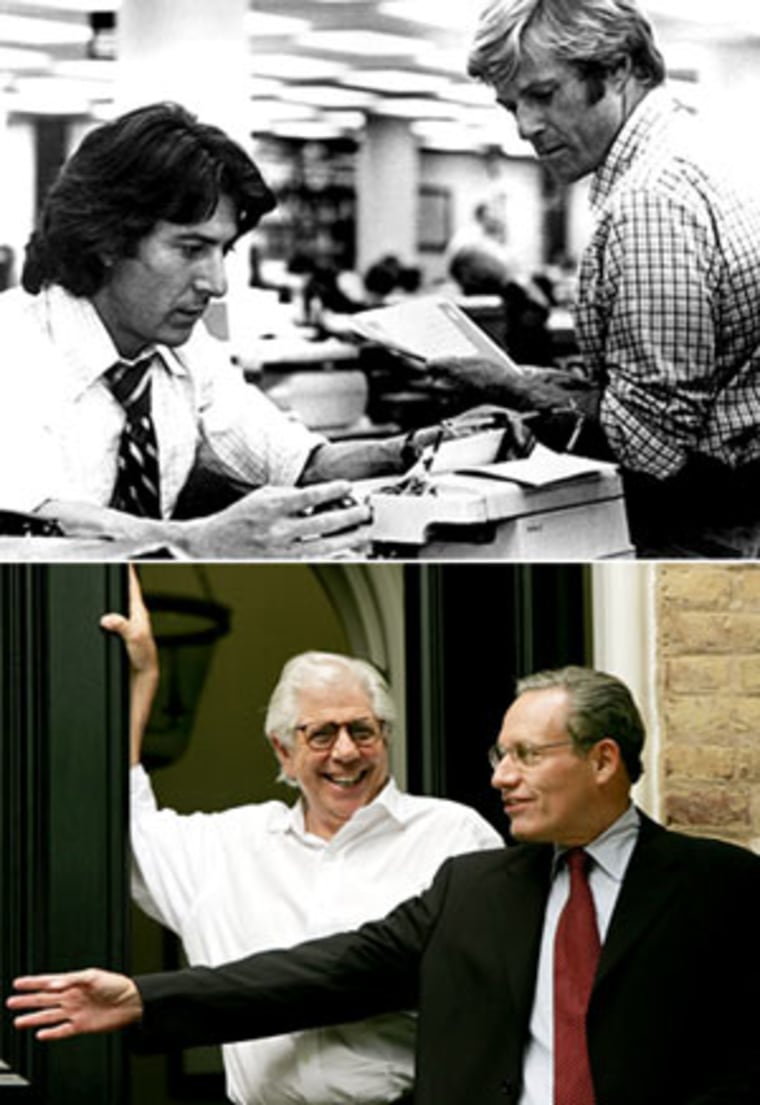

Woodward wasn't working this story alone. From the beginning, his partner was another young reporter — Carl Bernstein. They both quickly realized that the White House connection was a major development.

Carl Bernstein: It was unprecedented. And obviously we were a little awestruck. It gave us a special sense of responsibility.

They knew the FBI was also investigating. What they didn't know was that the White House was trying to limit that investigation.

"One of the first things we did after the Watergate break-in, and one of our concerns was, was where this investigation would go. And we were very concerned about that, that the investigation be very limited," says then-White House counsel John Dean.

It would be learned only later from the Nixon White House tapes that the president himself ordered his chief of staff, Bob Haldeman, to cover up the reasons for the Watergate burglary. Nixon ordered to tell the FBI, which was investigating, to back off.

But Woodward's secret source encouraged the young reporter to press on.

Woodward: [He said] “Keep going, young man. There is a lot here.” Clearly, this has gone from two or three on the Richter scale to 100.

In his notes on his secret source, Woodward referred to him as “X,” or "M.F." or “my friend.” But Howard Simons— one of Bob's bosses— came up with a more colorful name: "Deep Throat."

Woodward: At this point the managing editor had given him that very unfortunate name. Kind of by accident, it just kind of came out because it was on deep background.

“Deep Throat” was the title of a very popular and very pornographic film released in 1972.

The Post editors were anxious about the Watergate stories. This was high stakes journalism, going after the White House and Woodward and Bernstein were relatively low-level staffers. Federal prosecutors on the case didn't seem to be finding any larger conspiracy. And Nixon loyalists denied every story, furiously attacking the Post day in and day out.

The reporters could feel the pressure building, and so could "Deep Throat." He told Woodward they both had to be extremely cautious, that they should never talk on the telephone. And "Deep Throat" proposed an elaborate, clandestine scheme for their face-to-face meetings. If Woodward wanted a meeting, he needed to move a flower pot with a red flag on the balcony of his apartment. If “Deep Throat” wanted to meet, he would draw a clock on page 20 of The New York Times delivered each day to Woodward's apartment.

“Deep Throat” began insisting on meeting at 2 a.m. in a parking garage in Rosslyn, Va., just across the Potomac River from Washington. He ordered Woodward to change cabs on his way there, to walk the last several blocks, and to make sure he wasn't being tailed.

Woodward had never disclosed the exact location and never taken anyone there — until now.

Woodward: It was like the oracle had come down.

Brokaw: At any point do you say to yourself, Woodward, "What the hell have I got myself into here?"

Woodward: Yeah, all that time. But you want the information. You know this is a guy who can help you. Like no one else.

And in one of the first of those garage meetings, October 9th, 1972, almost four months after the Watergate burglary, “Deep Throat” made a promise.

Woodward: I have the notes that I typed that night. And the first line is him saying there is a way to untie the Watergate knot.

Brokaw: It was very reassuring to you wasn't it? To know you had this guy who said, “You're on the right track.”

Bernstein: It would have been more reassuring if I could get Woodward to see him more. I can't tell you how many times I said to Bob, I said, “Call that guy.” And Woodward said, “I can't get him. I can't get him.” “Move the damn flowerpot.”

With the help of “Deep Throat,” Woodward and Bernstein were finally putting the puzzle together. For the first time they tied the Watergate burglary to the broader dirty tricks campaign.

Then, at another meeting in the garage, “Deep Throat” told Woodward the conspiracy reached right into the president's inner circle.

Woodward: He said it was a Haldeman operation. So the White House Chief of Staff ran it all and knew about it.

About that time, it dawned on them that the conspiracy could involve the president himself.

Brokaw: You were having a little meeting up in the Washington Post.

Woodward: Yes, the little cafeteria where they have the worst coffee in America.

Bernstein: And I pressed the button for this awful coffee in the machine. And I felt a chill. I remember it to this day. I turned around to Woodward and said, “Oh my God, this president is going to be impeached.”

Woodward: I realized this was no flight of fancy. And said ,“You're right.” And we paused and kind of held the moment and I said, "We can never say that in this newsroom ever." Because people would think we had some agenda or there was a political motive.

They were choosing every word so carefully — but there was a problem. Nobody was paying attention.

Brokaw: The rest of the press is not picking it up very much. The public is not responding to it. Richard Nixon has a triumphant second inaugural.

Woodward: Triumphant in a way — you don't get a victory like he got.

Less than five months after the Watergate break-in, Richard Nixon won re-election with 61 percent of the vote, one of the biggest landslides in presidential history.

"Deep Throat" had promised to help untie the Watergate knot, but so far it was holding fast.

Bob Woodward began to cultivate the most famous anonymous source in history before he was even a reporter. It was 1970. Woodward was finishing a tour in the U.S. Navy. He was delivering classified documents to the Nixon White House.

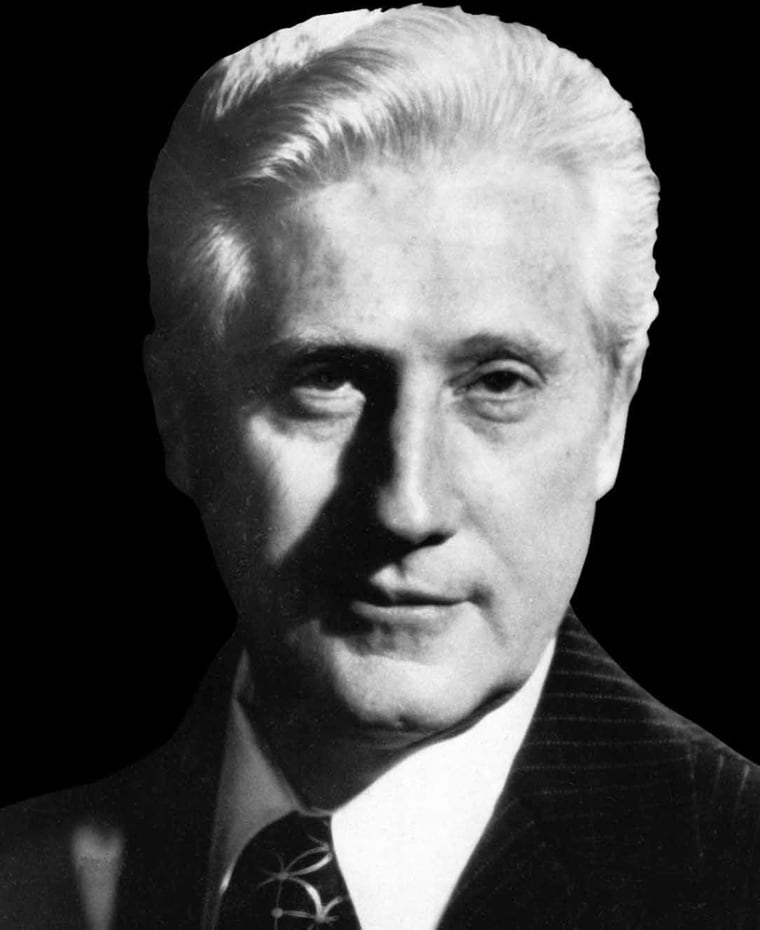

As Woodward sat in a small waiting area outside the situation room, a tall, distinguished-looking older man sat down beside him. Woodward started to talk... and talk. He tells the story in his new book, “The Secret Man.” It was a chance encounter that would change history. Because Woodward's captive listener turned out to be W. Mark Felt — one of the top men at the FBI.

Brokaw: You pour your heart out to him. You're a needy young man.

Woodward: I was adrift. I had no idea what the the future was. And here was a moment — like two passengers on this airplane — kind of condemned to be together. 'Cause he was waiting to see somebody.

Brokaw: He was this kind of flamboyant character, a “G Man” through and through. Did that appeal to you at that time?

Woodward: Well, it was his reserve. And that sense of here's somebody who's on the inside of the secrets.

Brokaw: You write in your book, “The hook was set.” That sounds like you were using him.

Woodward: Yes. And—I was. Kind of—as career counselor I called him my friend. But he was 25, 30 years older. He was kind of like an extra father.

Brokaw: The extra father notion. That's a pretty strong relationship.

Woodward: It is. Yeah.

Brokaw: You know that the real and amateur psychologists out there watching all of this are going to be intrigued by how that relationship developed.

Woodward: Yes. And I share the intrigue.

Woodward must have made a very good impression —at the end of the meeting Felt gave him his direct telephone number at the FBI. When Woodward left the Navy and became a newspaper reporter, the FBI man helped him on some stories. Mark Felt didn't have much use for the press. But he trusted the young Bob Woodward.

Brokaw: Do you think he saw you as a bright, upstanding young man just out of the Navy? And that was maybe part of the reason for the bond that he quickly established?

Woodward: There's a tendency to remember people in the role they have when you meet them. And I was wearing that Navy uniform. I was as buttoned down as he was.

As Woodward's career was just beginning to take off, Mark Felt was going through a career crisis. His mentor and his idol, the powerful and controversial J. Edgar Hoover died — the man who built the FBI. Felt thought he deserved to be named Hoover's successor, but Nixon wanted his own man, his own pipeline into the FBI. He named L. Patrick Gray, a little known Nixon loyalist without many distinguishing credentials.

"Here was a guy who had no law enforcement experience whatsoever," says FBI historian Ron Kestrel. "And turned out to be so malleable that he would actually involve himself in the cover-up." In the middle of the Watergate investigation, Patrick Gray actually took incriminating documents to his home and burned them.

By now Felt was the number two man at the FBI, but he was plainly unhappy with the turn of events. He kept Woodward on course in the Watergate investigation.

While Patrick Gray himself believes that Mark Felt leaked because he was angry he didn't get the top job at the FBI, Ben Bradlee, who at the time was executive editor of the Washington Post, thinks that wasn't the motivation at all.

"Obviously he wanted that story out or he wouldn't have talked to Woodward. He wanted to shine a light into that dark corner," says Bradlee.

Brokaw: Psychologically, the relationship changed a little bit here, didn't it? There's very little time to talk about your career or how he's doing...

Woodward: That's for sure. No career discussion at this point. We are in the big casino.

The White House was going ballistic about the leaks. And at one point Nixon's chief of staff, Bob Haldeman, told the president he thought he knew who was talking — W. Mark Felt. But they were reluctant to go after Felt, because he knew too much.

Even as the White House suspected that Felt was talking, Felt was involved in his own cover-up of his role as "Deep Throat." FBI memos from the Watergate era show that when Nixon's men demanded that the FBI find out who was leaking to the newspapers, Felt himself ran the investigation.

Brokaw: He was the ultimate agent.

Bernstein: Yeah. He was really good at it.

Brokaw: And you had no idea this was going on while you were talking with him?

Woodward: No, of course not.

By the spring of 1973, thanks in part to Woodward and Bernstein's reporting, the Watergate investigation was exploding. The president's men were beginning to turn on each other. The Senate was about to begin hearings. And down in the garage, “Deep Throat” told Woodward something genuinely frightening.

Woodward: He was really wrought up. He was tighter than a drum. And this is when he said: "The stakes are so high everyone's life is in danger. There's wiretapping going on. You have no idea what these people will do." It really scared the bejesus out of me.

There were a series of stunning developments in the Nixon White House in the first half of 1973.

When Federal Judge John Sirica began handing out stiff prison sentences to the Watergate burglars, burglar James McCord started naming conspirators at the highest levels.

Soon Nixon's closest aides, H.R. Haldeman and John Ehrlichman, were forced to resign. White House counsel John Dean was fired.

In May, the Senate Watergate Committee began those nationally televised hearings. John Dean was a cool, methodical witness against his old boss.

During the hearings there was also this remarkable disclosure: There were tapes of the most sensitive and potentially the most incriminating conversations about Watergate.

“The tapes were dynamite with a fuse burning ready to go off. And ultimately did go off,” says Leonard Garment, then counsel to the president.

Only a few people knew what was on those tapes. In one of his most important leaks, “Deep Throat” revealed something that would help destroy Nixon's credibility.

Mark Felt, in the underground garage, tells Felt there is tampering with the tapes and that there are some erasures.

A couple of days later in the courtroom, they announced the 18 and a half minute gap. In a convoluted, complicated case, everyone could understand this: If someone erased an incriminating tape, then the cover-up was for real.

The White House claimed the president's secretary, Rosemary Woods, accidentally erased that tape and released a photograph claiming to show how she might have done it. The photograph became a national joke — the “Rosemary Stretch.” The clock was ticking on the Nixon presidency.

Woodward and Bernstein began to write their first book on Watergate, “All the President's Men.” Some of their previously anonymous sources agreed to be named.

Was it time to tell the world the identity of their key source, “Deep Throat”? By now Mark Felt was retired from the FBI. Maybe he would come forward?

Brokaw: Did you say to Mark, "I really want to write your name. I want to tell everyone"?

Woodward: Yeah. "You're out of the FBI. Come on, let's tell this story. You should feel good about it." And it was, “No! Are you crazy, out of your mind?” He just said flat out, "No, no, no!"

The book came out in April, 1974, as the Watergate crisis was heading toward a dramatic climax. It was the first time that Mark Felt learned of his colorful nickname. In the book, Woodward also described in detail how and where they met and the nature of the critical information that Felt had provided.

Suddenly everyone was consumed with the guessing game: Who was Bob Woodward's secret source? Who was “Deep Throat”?

Woodward: I was listening to the local radio station here. They devoted 10 or 15 minutes to reading excerpts about the meetings with "Deep Throat." And soon thereafter I called Mark Felt at home. The worst thing happened: He hung up. And it was just like a stab.

Woodward thought Felt was personally insulted.

Woodward: All of a sudden in this book, which was getting a great amount of attention, [he] is known as “Deep Throat,” one of the most celebrated pornographic movies of the era. I wouldn't want to be known as “Deep Throat” frankly in that sense.

Felt had taken a huge risk in talking to Bob Woodward. If the FBI man was found out, he could become a pariah in the FBI culture he so cherished.

And at the moment, Felt had plenty of other problems. As Bob Woodward's star was rising, the life of Mark Felt, the secret man, was taking a sharp turn in the other direction.

By 1974, the Nixon White House was a bunker, where the president and what was left of his loyal staff were holed up and holding out against wave after wave of bad news.

White House Counsel John Dean had pleaded guilty to conspiracy to obstruct justice and he was headed for prison. Many of the president's top aides were indicted on felony charges and later sent to prison.

In the House Judiciary Committee, Republicans joined Democrats in voting for articles of impeachment. And, in a unanimous ruling, the Supreme Court delivered the coup de grace—ordering the president to give up the remaining White House tapes. The president had no choice. On one tape you could clearly hear Richard Nixon ordering a cover up of the investigation.

Days later, Richard Milhous Nixon became the first American president forced to resign the office.

Brokaw: The next day, did you want to dial Mark Felt?

Woodward: Yeah, I did, and I wanted to kind of talk it through. But the last I'd heard from him was the hang-up treatment.

Brokaw: You didn't want to drive out there as you had before when you needed to have a meeting with him?

Woodward: Yeah, I didn't need more information at that point. There was too much.

Brokaw: But people looking in are going toa say, “Wait a minute, he's done with him. You know, he's used him up. He's gotten everything out of him."

Woodward: But I'm also trying to protect him, but I also am gutless. I so testify.

By now Woodward and Bernstein were household names — and wealthy.

“Deep Throat” also had an anonymous fame — but Mark Felt didn't want to cash in on it. Besides, he was soon in a lot of legal trouble.

With J. Edgar Hoover gone and Nixon in disgrace, any past abuse of power became fair game. It was revealed Felt had authorized so-called black bag jobs — burglaries, carried out by the FBI to gather intelligence against members of the radical anti-war movement.

Now Mark Felt — “Deep Throat” — was a suspect in a series of FBI-directed burglaries. Felt was going be investigated for, of all things, authorizing break-ins.

Bob Woodward's compass and mentor during Watergate was at a low point in his life.

Brokaw: But you don't call him during that time—

Woodward: No—

Brokaw: —in any personal way.

Yet Woodward did call Felt to get a newspaper story about those FBI black bag jobs.

Woodward: He gave me an on the record interview saying, “Oh, these burglaries were absolutely necessary. They were authorized. It was this time of peril and violence in America.”

Brokaw: But your relationship has changed at this point, Bob. It's a lot less personal than it was before?

Woodward: Oh, it sure is.

Just as Mark Felt, the man, was entering this very dark period of his life, “Deep Throat,” his alter ego, was at the peak of his celebrity, played powerfully by Hal Holbrook in the 1976 movie version of “All the President's Men.”

Brokaw: Did he go see the movie?

Woodward: I don't know.

Brokaw: You never talked to him about it?

Woodward: I never talked to him about that.

Brokaw: You never asked him, “What did you think of the movie?”

Woodward: No, because we were not—

Brokaw: You were not at a good stage at that point?

Woodward: We weren't.

In real life, Bob Woodward and “Deep Throat” only met about a half a dozen times in that his garage. But the eerie and realistic garage scenes from “All the President's Men” are fixed in the memories of movie fans. The filmmakers had never seen the real garage. Woodward never showed anyone where it was... until now.

Woodward: It is a little frightening. The whole thing is frightening. At night it's so quiet. You're so alone. You realize that you've kind of given yourself over to a process that somebody else is controlling. And it's unnatural.

It was also in the garage that the fictional “Deep Throat” uttered the movie's most memorable line: “Just follow the money.”

It was a phrase, it turns out, that never appears in Bob Woodward's extensive notes of his conversations with the real “Deep Throat.”

So who gave the fictional “Deep Throat” his most quoted line? It was screenwriter William Goldman.

“It's just a thing that he would have said, and he says it several times, ‘Just follow the money' and it caught on,” says William Goldman.

And what did it take for the young Bob Woodward to descend into that garage in the dark of night? Robert Redford thought about that as he prepared to play Woodward.

"Bob was a genuine gentleman and a man that was very concerned about well-being and dignity and so forth. But underneath that was another person that was relentless, tenacious, almost savage in his pursuit of getting a story, particularly getting the truth," says Redford.

The movie imprinted “Deep Throat” in the imagination of millions, millions who wondered — who was this guy?

Almost from the beginning, some people suspected Mark Felt. It was a national whodunit. Maybe it was Al Haig, Nixon's chief of staff in the final days. Maybe it was former Nixon speechwriter Pat Buchanan. Maybe it was Diane Sawyer, who worked at the White House in those days.

Woodward had told only a few people the real identity of his source. Woodward didn't tell his boss, Ben Bradlee, until after Nixon resigned. But Carl Bernstein knew almost from the beginning.

Bernstein never told his then-wife, author and filmmaker Nora Ephron. But Ephron, a former reporter, was her own best detective.

"The first is that Woodward always referred to 'Deep Throat' before he was christened 'Deep Throat' as 'my friend.' And the initials of “my friend” — M.F. —are the initials of Mark Felt," says Ephron. "And that, to me, was a dead giveaway."

Woodward sheepishly admits he even put those initials “M.F.” in some of his notes. “Not very good tradecraft on my part,” he now says.

Guessing the identity of “Deep Throat” may have been a parlor game to some, but keeping it secret was no game to Mark Felt.

That secret almost spilled out in 1976, when Felt landed in front of a federal grand jury.

“[Felt] said, ‘I had so much business at the White House, some people thought I was ‘Deep Throat,'” recalls Stanley Pottinger, the prosecutor who questioned Felt.

According to Pottinger, one of the grand jurors then raised his hand, turned to Felt, and asked, "Were you?"

"And, at that point, Felt flushed bright red," says Pottinger. Then Felt, under oath, answered “no.” Pottinger immediately knew that something was wrong. Pottinger says he approached Felt and spoke in a whisper the grand jurors could not hear.

To Felt, Pottinger says, "'Mr. Felt, I have to remind you that you're still under oath, but I don't think that question is relevant to these proceedings. So if you'd like I'll be happy to withdraw the question and your answer. It's your decision."

Felt replies, “Withdraw the question,” still flushed.

"Now if demeanor ever speaks as loudly as words, he had acknowledged that he was ‘Deep Throat,'" says Pottinger.

Remarkably, Stanley Pottinger kept the secret. All this was only revealed in Woodward's new book.

And what of the secret man, the real “Deep Throat”? In 1980, he went on trial for authorizing FBI burglaries. And, ironically, the key witness for his defense was former President Richard Nixon.

Brokaw: You can't make this stuff up, Bob.

Woodward: That's exactly right. And at one point, I call Felt and he points out that The Post has written an editorial saying he should go to jail. Felt, with full justice says, “I'm getting more help from Richard Nixon than The Washington Post.”

Brokaw: What did you think when you read that?

Woodward: The word that comes to mind is "ghoulish."

Mark Felt was convicted of authorizing those FBI black bag jobs — a felony. That brought some satisfaction to White House aides who had been fingered by Felt.

“There is a degree of irony when you look at the fact that Mark Felt was distressed by Nixon's so-called abuses of power,” says John Dean.

Felt went on to publish his own life story, “The FBI Pyramid.” Almost no one read it. But knowing what we know now, it does provide a window into his mind.

On the dustcover, Felt allowed them to print, “Mark Felt, who was rumored to be famous informer, 'Deep Throat.'”

Brokaw: He'd raise it himself and then deny it. In this book, he says flat out three different times, “I was not the source of information for Woodward and Bernstein. I did not leak information.”

Woodward: Right. And he never leaked to Woodward and Bernstein, because Carl never met him. And, so, you know, maybe there's some twist in his mind of, “Well, I never leaked to both of them.” I don't know. But the denial is very powerful.

Which is what made this year's revelations all the more unexpected.

In 1981, Washington Post columnist Richard Cohen talked to Nora Ephron and became convinced Felt was “Deep Throat.” He mentioned it to Woodward, who was now an editor at the Post.

Woodward: I tried to discourage him. Richard is not easily discouraged and he says he's going to write it anyway. And I said, “Well, you wouldn't want to be wrong." And I lied to protect my source.

Cohen says he now understands that Bob Woodward had his reasons for lying. President Ronald Reagan had just pardoned Mark Felt.

"I thought Bob did the right thing in lying to me. It was a dramatic critical moment for Mark Felt," says Cohen. "I think if Reagan had known he was ‘Deep Throat,' Reagan would not have pardoned him."

After Felt's pardon was another twist: Richard Nixon sent champagne to the very man who helped bring him down. Felt then faded into obscurity.

Bob Woodward did not talk to Mark Felt for almost 20 years. The relationship that began with a chance meeting, then became a kind of father son relationship, then reached an excruciating intensity during Watergate... just withered.

In 1999 however, the “Who is ‘Deep Throat'?” game came back again, as it did very few years. A Hartford newspaper reported that a son of Carl Bernstein and Nora Ephron years ago had told a friend at summer camp that Mark Felt was “Deep Throat.”

Woodward: I started thinking, “You've gotta get this story down. You need to see if there's some sort of kind of closure or reconciliation.” So in 2000, I went out to see him in Santa Rosa, California and just showed up on the doorstep.

It was reminiscent of the old days, in the 1970s, when Woodward would call on Felt at home, only now the roles were reversed: Woodward was the the famous journalist riding in a chauffeured car. Felt was the unknown, now an 86-year old man with a fading memory, living in his daughter Joan's converted garage in California.

Woodward was apprehensive as he knocked on their front door.

Woodward: Seeing him when he came up from the basement, he was so physically able at that point. He still had that mantle of gray hair, still that had deep voice of command. I had a feeling of happiness of kind of, you know, we'd been reunited.

Bob Woodward recorded a conversation with Mark Felt that day, probing to see what Felt remembered:

Woodward: Remember back in those years when we met and chatted, and any—Felt: Well, I think I remember the area and a time, but I don't remember specifically anything.

Woodward soon found that Felt had no specific memories about the Watergate era. The powerful Hoover protege, the mysterious source in the garage, the embattled G-man — all those people he had known were gone.

Woodward: You remember the Nixon period, a little bit?Felt: Vaguely. But I, but I still don't have any specific recollections from it.Woodward: Do you remember when you met him? When you met Nixon?Felt: I can't remember. I met him, but I can't remember when it was.

We'll never get to meet the “Deep Throat” Woodward knew 35 years ago. We can only get a sense of his personality from artifacts he left behind, like the photo on the jacket of Felt's memoir, or the way he signed off on those FBI memos.

Woodward: Yeah. Right.

Brokaw: It's like something out of a ‘40s Hollywood dossier of some kind.

Woodward: Central casting.

Although by the time they were reunited, Felt seemed to have no memory of his historic role, Woodward believed that he was still obligated to protect Felt's secret.

Woodward: I thought, “Oh. How do we keep that cork in the bottle in a way that's in his interest?”

Brokaw: Probably in your interest as well, because you were writing a book about it, right?

Woodward: Well, the book is the obligation to tell the story. If he was competent and wanted to write a book with me, I'd be all for that.

Felt's daughter said her father might be suffering dementia. Woodward wrote the book and locked it away.

Then, on May 31, 2005, almost 33 years after Watergate, Felt's family revealed the secret in Vanity Fair: Mark Felt was “Deep Throat.”

“Mark had expressed reservations in the past about revealing his identity and about whether his actions were appropriate for an FBI man,” said Nick Jones, Felt's grandson. “But as he recently told my mother, I guess people used to think 'Deep Throat' was a criminal, but now they think he's a hero. My grandfather is pleased that he is being honored for his role as 'Deep Throat' along with his friend Bob Woodward.”

Later that day, Woodward confirmed that Mark Felt was Deep Throat. The best kept secret in all of journalism was finally disclosed.

But questions remain: Did Bob Woodward enrich himself at Mark Felt's expense? Felt says he'd like something too. Woodward and the Post have discussed ways that Felt might be compensated, but there are so many obstacles.

Woodward: We can't start down that slippery slope in our business of paying sources. You know, what Mark Felt and I were able to do is have one of the most clandestine, intimate reporter-source relationships without crossing some line of money or ethics or obligations.

In the end, Felt's family signed book and movie deals reported to total close to $1 million. (The Felt family was contacted, but refused to comment for this story.)

And then, there's the biggest question of all: What to make of Mark Felt?

Some who worked in the Nixon White House are still angry at Felt for leaking.

“I think he's a snake,” says MSNBC commentator and former Nixon speechwriter Pat Buchanan. “He had broken his oath. He had dishonored his code to his fellow members of the FBI. And that's why he lied for 30 years about it.”

Woodward still protects the source he called, “my friend.”

Woodward: First of all, he'd done his job. He'd been right about Nixon. We had been right about Nixon.

Brokaw: His son says he was a hero. Do you think he was a hero?

Woodward: You know, I don't know what heroes are. I wouldn't put label “hero,” “no hero.” I would say he's a man of immense courage and should there come a moment when all of us get tested. Should we display equivalent amount of courage, then we should feel pretty good about ourselves.

About 31 years ago this summer — 1974 — the White House had a funereal air about it. Richard Nixon was just hanging on as president and by mid-August he would be gone, brought down by his own paranoia and corruption of power.

Would that have happened without Woodward and Bernstein, the Washington Post, and especially "Deep Throat" — Mark W. Felt, the secret man who knew the secrets? That's another part of the endless Watergate guessing game.

We don't know, just as we don't know what motivated Mark Felt to get so uniquely involved in exposing the abuses in the White House — or what led Richard Nixon to believe he could get away with it.