Far from home, a U.S. Coast Guard cutter plows its white bow through the seas of West Africa’s Gulf of Guinea, where an oil boom could outpace Persian Gulf exports to America in a decade.

The ship’s presence here is a sign of U.S. military and financial interest in an increasingly strategic part of the world — one American officials say is vulnerable to piracy, political instability and terrorism.

The potential dangers are clear with 3,000 miles of virtually unpoliced coastline that’s home to billions of dollars in U.S. oil industry investment alone.

“It’s a lot of water with not a lot of security,” said Lt. Cmdr. Daniel Trott, a strategy specialist for U.S. Naval Forces Europe, whose area of responsibility includes most of Africa. “And where there’s a lack of security, there’s an opportunity for bad actors to show up.”

Though U.S. officials cite no current terrorist activity in the Gulf of Guinea, homegrown al-Qaida-linked groups or cells are thought to be active across Africa, especially in countries with large Muslim populations like Algeria, a longtime oil producer, and Mauritania, which is poised to start pumping crude next year.

In U.S. plans, and terrorists’

In Nigeria, the fifth-biggest source of U.S. oil imports, a phoned-in terrorist threat in June forced the U.S. consulate in Lagos to close for several days. Al-Qaida chief Osama Bin Laden purportedly marked Nigeria for “liberation” in a release posted on the Internet.

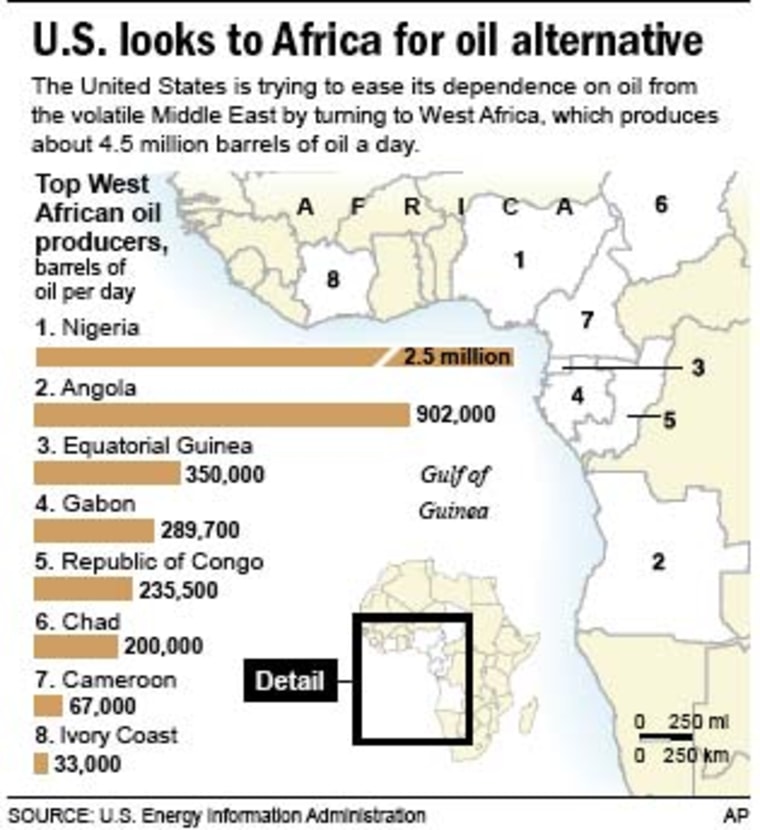

The United States is trying to ease its dependence on oil from the volatile Middle East by turning to West Africa, which produces about 4.5 million barrels of light, sweet crude a day.

Led by top African producer Nigeria, the Gulf of Guinea already delivers about 15 percent of America’s oil supply. By 2015, that figure may swell to 25 percent, according to the U.S. National Intelligence Council, a CIA think-tank.

The Persian Gulf, by contrast, accounts for about 22 percent of U.S. imports, according to the U.S. government’s Energy Information Administration.

$33 billion earmarked for region

Over the next five years, 1 in 5 new barrels of oil on the global market will come from the Gulf of Guinea, and more than $33 billion will be invested in the region, 40 percent of it from American companies, the Washington-based Center for Strategic and International Studies estimates.

Stretching roughly from Ivory Coast to Angola, the Gulf of Guinea is relatively unfamiliar to U.S. forces, and tours of the region such as last month’s by the Coast Guard are aimed at shaking hands, gaining familiarity and assessing threats to oil access.

The 100-man crew of the Portsmouth, Va.-based cutter, temporarily assigned to the Navy’s 6th Fleet, paid brief visits to Cape Verde, Ghana, Benin, Equatorial Guinea and Sao Tome and Principe, a tiny two-island republic whose capital’s seaport is so small that the 270-foot vessel had to anchor offshore.

One recent morning, half a dozen Sao Tomean sailors hopped aboard an orange American Zodiac boat, taking instruction from U.S. sailors on man-overboard lifesaving exercises. On land, another group gathered around a mustachioed American showing them how to repair an outboard motor.

No illusions about why Americans are there

That afternoon at a peach-colored seaside high school, the only one in a country of about 150,000 people that’s roughly five times the size of Washington, D.C., a few U.S. crewmen fixed door hinges in what was clearly a public relations campaign.

Sao Tomean officials warmly welcomed the three-day American presence, but they were under no illusions.

“Unfortunately, Americans are interested in Sao Tome because of oil, but Sao Tome existed before that,” said Carlos Neves, national assembly vice president.

Sao Tome doesn’t have any proven reserves, but the search is under way and the government has awarded some exploration sectors to American and other companies.

Think tanks like CSIS are pushing for a greater U.S. role in the region to protect American interests. But with its own military assets tied up elsewhere, including the Persian Gulf and Iraq, the United States is not looking to take the lead in the region — at least not yet.

“We don’t have the resources to provide maritime security here. We’re not going to be the force in the Gulf of Guinea,” Trott told The Associated Press at a hotel in palm-fringed Sao Tome, capital of the archipelago perched on the equator.

“But we are looking to increase our involvement right now — not to send ships on patrols, but to develop partnerships and develop capacities,” he said. “If the Navy had more assets, would they send them here? Probably. But our first choice is to use what we have to facilitate training and regional cooperation.”

Cutter Cmdr. Bob Wagner described the mission to develop African maritime security as “preventive work to keep terrorists from the seas.”

The only U.S. military base in Africa is in the Horn of Africa nation of Djibouti, the hub of anti-terrorism efforts on the continent.

U.S. base for Sao Tome?

Sao Tome has been touted as the possible site for a new U.S. naval base, but officials from both countries said no such plans were in the works.

A top U.S. diplomat said U.S. forces may use storage facilities on Sao Tome as they do in other parts of Africa: to preposition equipment and supplies for emergencies, but no more.

U.S. involvement today is limited mainly to a yet-to-be-completed feasibility study on expanding the airport and building a deep-water port in Neves, north of the capital, in anticipation of a massive local oil boom.

The U.S. isn’t offering to construct either, however, and deeply impoverished Sao Tome can’t do it alone.

Showing Sao Tome lawmakers around the cutter’s bridge, Wagner spread out a large map of the country, its maritime boundaries highlighted with a black pen. Underlining Sao Tome’s desperate state, local coast guard chief Capt. Joao Idalecio asked if he could have a copy.

So much oil, so little protection

The tiny size and inexperience of Africa’s maritime forces, and the lack of cooperation between them, are chief concerns.

Sao Tome and Principe’s coast guard is just 50 men and two inflatable zodiacs — clearly inadequate to patrol a vast, yet-to-be-exploited zone it shares with Nigeria that’s believed to contain up to 11 billion barrels of oil.

Petrol facilities and oil rigs in other places are also vulnerable. In Equatorial Guinea, for example, some U.S. oil platforms are protected not by that government’s minuscule navy but by private, unarmed guards.

Fostering political stability and keeping oil flowing are key U.S. goals, particularly in Nigeria, which exports about 2.5 million barrels daily, half of it to the United States.

Militia attacks and threats against foreign oil workers in Nigeria’s oil-rich delta have cut hundreds of thousands of barrels of daily oil production. Muslim-Christian violence in the volatile country’s north has killed thousands.

Another overthrow

On Wednesday, army officers overthrew the U.S.-allied president of Islamic Mauritania, which had been increasingly looking to the West and citing a growing threat from al-Qaida-linked militants.

Equatorial Guinea and Sao Tome have both been struck by coups and attempted coups over the past few years.

Washington had in the past shunned Equatorial Guinea, run by Teodoro Obiang, a longtime dictator who had his predecessor — his uncle — executed by firing squad. But with the tiny nation’s newfound oil wealth, that has begun to change. The visit to Equatorial Guinea was the first by U.S. forces in 13 years.

U.S. officials said most countries welcomed the American visits, though one officer described Equatorial Guinea military officials as “distant and standoffish,” speculating their estrangement was because of growing Chinese influence there.

Encouraging intelligence-sharing and helping nations prepare for potential terrorist threats is another U.S. strategy.

‘Have to start somewhere’

It’s similar to what the U.S. is trying to do elsewhere on the continent, particularly the vast, ungoverned stretches of open desert that sweep across northern Africa, where U.S. forces conducted joint training exercises with African armies this summer.

In October, the U.S. Navy hosted a first-ever gathering in Italy of Gulf of Guinea naval officials. A similar conference is planned for Ghana in December.

Idalecio said Sao Tome hoped to expand its own coast guard, mainly to protect against illegal fishing and piracy.

Wagner acknowledged the monumental task under-equipped African naval forces face.

“You have to start somewhere,” he said, watching a friendly soccer match pitting U.S. sailors against their Sao Tome counterparts on a dusty pitch overlooking the city. “But there’s a recognition that they need to improve.”