The first images ever made of retinas in living people reveal surprising variation from one person to the next. Yet somehow our perceptions don't vary as might be expected.

As they took pictures of the thousands of cells responsible for detecting color in the deepest layer of the eye, scientists found that our eyes are wired differently. Yet we all — with the exception of the colorblind — identify colors similarly.

The results suggest that the brain plays an even more significant role than thought in deciding what we see.

The eye, responsible for receiving visual images, is wrapped in three layers of tissue. The innermost layer, the retina, is responsible for sensing color and sending information to the brain.

The retina contains light receptors known as cones and rods. These receptors receive light, convert it to chemical energy, and activate the nerves that send messages to the brain. The rods are in charge of perceiving size, brightness and shape of images, whereas color vision and fine details are the responsibility of the cones.

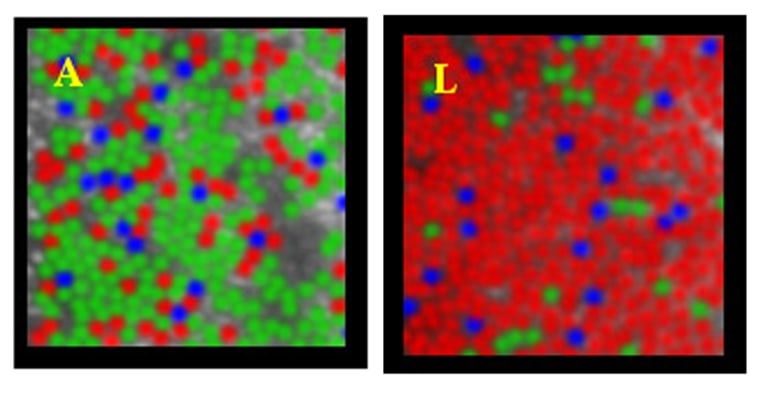

On average, there are 7 million cones in the human retina, 64 percent of which are red, 32 percent green, and 2 percent blue, with each being sensitive to a slightly different region of the color spectrum. At least that's what scientists have been saying for years.

But the first complete imaging of the human retina, mapping the arrangement of the three types of cone photoreceptors, revealed something surprising about these numbers.

Big variation

The study found that people recognized colors in the same way. Yet the pictures of their retinas showed there is enormous variability, sometimes up to 40 times, in the relative number of green and red cones in the retina.

"[This] suggests that there is a compensatory mechanism in our brain that negates individual differences in the relative numbers of red and green cones that we observed," Joseph Carroll, a researcher at the Center for Visual Science at University of Rochester and a collaborator of the study, told LiveScience.

The researchers took advantage of adaptive optics imaging, which uses a camera containing a corrective device that cancels the effects of the eye's imperfect optics on image quality, to produce a high-resolution retinal picture.

Borrowing from astronomy

"Adaptive optics is a technique borrowed from astronomy, where it is used to obtain sharp images of stars from telescopes on the ground," said David Williams, director of the Center for Visual Science. "All such telescopes suffer from blur due to the effects of turbulence in the Earth's atmosphere. In our case, optical defects in the cornea and lens of the eye blur images of the retina."

The measured defects were corrected using deformable mirrors, which bend and morph according each person's eye, before taking high-magnification pictures of the eye. This allowed Williams and colleagues to see and map single cells such as the cones.

The researchers hope to use the same techniques to better understand various forms of colorblindness and different kinds of retinal disease.

The findings were detailed in a recent issue of the Journal of Neuroscience.