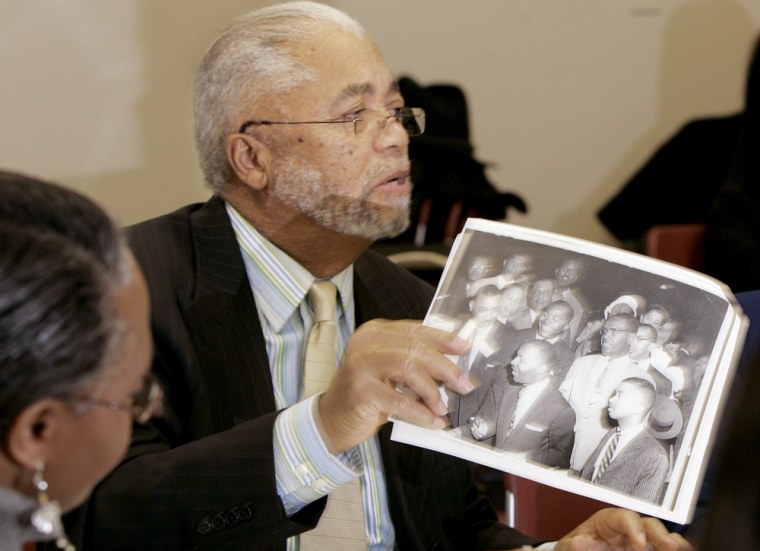

The first book Assemblyman William Payne recalls hearing as a kindergartner in the 1940s was “The Story of Little Black Sambo.” He never forgot the black stereotypes that filled the 19th century children’s story.

“You grow up with these subliminal messages that everything good is white,” Payne recalled, his words bubbling forth with angry urgency. “It is so hurtful that these things were sanctioned by the Board of Education.”

The memory was part of what drove Payne decades later as he wrote and lobbied for a state law — the nation’s first — mandating that New Jersey schools teach black history. But now, nearly four years later, compliance is spotty and the lawmaker is frustrated. Even as Black History Month briefly draws attention to African-American heritage, New Jersey’s effort shows how hard it can be to move from an idea to change in the classroom.

“We won’t have to do February if in fact we teach this in the regular curriculum,” Payne said.

New Jersey’s 2002 law created an Amistad Commission whose members write lesson plans, organize educational events and train teachers — all focused on black history. The law says each school board “shall incorporate” black history at all grade levels. Two other states, New York and Illinois, have since passed similar laws and several others are either considering them or have passed statutes that encourage, but do not require, teachers to address black history.

Amistad absent

New Jersey’s commission gets its name from a Spanish ship that was carrying kidnapped Africans into slavery in 1839 when the captives seized the boat. They were recaptured and imprisoned, but eventually won their freedom in a U.S. Supreme Court ruling.

Even though Steven Spielberg released a movie about the incident in 1997, it’s often not included in history books — along with many other key events in black history, said Karen Jackson-Weaver, who was hired last year as the Amistad Commission’s first executive director.

Jackson-Weaver now is surveying New Jersey’s 593 districts on their compliance with the law. “Just in case you didn’t know,” she told districts in a letter, “we do have an Amistad law on the books and it’s necessary to have African-American history in the curriculum.”

Educators plead ignorance

Some educators don’t know the law exists. Among those that do, many teachers are not well-versed in black history and don’t know where to find teaching materials.

With just two full-time staffers, the Amistad Commission is struggling to help. The 19 volunteer commissioners are working to get lesson plans online, and will likely end up hiring an historian to write a textbook that adequately meshes black history with the rest of American history, Jackson-Weaver said.

Last week, New Jersey’s education commissioner sent another reminder letter to school districts to urge educators to implement the law.

“A law that isn’t enforced is like no law at all,” said Jerome Carr, a parent who pressed officials in Montgomery Township schools, about 30 miles north of Trenton, for two years to comply with Amistad. School officials ignored him, Carr said, and one board member questioned the need for a black history class.

‘Short shrift’ treatment lamented

Last month, the board approved a new multicultural elective called “Diversity in America,” but Carr reviewed the class outline and said it “continues to give short shrift to our history.” Jane T. Plenge, assistant superintendent for curriculum and instruction in Montgomery Township, said the district has been responsive to parents’ concerns and is constantly updating its social studies lessons.

Meanwhile, other New Jersey educators said their students have appreciated learning more about black history.

“When children begin to understand who they are, when they begin to see that they are part of history,” said Lauren Cooper, a middle school reading teacher at Belleville Middle School near Newark. “You can see them walking around school walking a little taller.”

Making sure youth learn all of American history is one reason lawmakers mandate lesson plans — and it’s nothing new. For decades, ethnic groups have pushed state lawmakers to require including their stories in class. Schools in Arizona, Alaska and New Mexico must teach about American Indians, and a Rhode Island law outlines lessons on the Irish potato famine.

But Payne knows it’s hard putting the laws into action. This year, he plans to introduce legislation aiming at strengthening New Jersey’s statute: requiring all new teachers get black history training, standardize textbook purchasing and make students pass a social studies exam before graduating. He also has plans to hire more commission staff.

“I want to make sure that when Bill Payne is gone, Amistad will keep going,” he said.