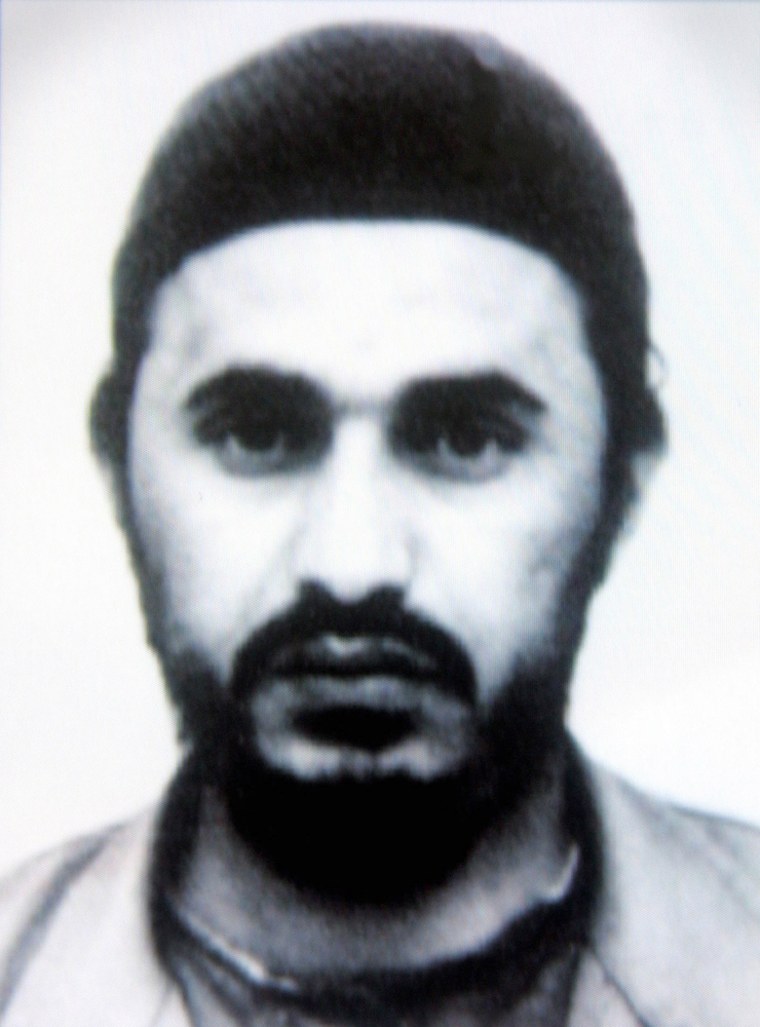

Terror leader Abu Musab al-Zarqawi has sharply lowered his profile in recent months, halting his group’s Internet claims as the number of big suicide bombings in Iraq — his infamous signature form of attack — has fallen.

Now, a man with close ties to Iraqi insurgent groups claims al-Zarqawi was shunted aside as political leader of a recently formed coalition of militants because they were angry at his propaganda efforts and embarrassed by his group’s deadly attack on hotels in Jordan.

But others caution the claim is hard to verify — and that perhaps the insurgents are just changing tactics.

Even if the report is true and al-Zarqawi has a lesser role, that does not mean the deadly violence in Iraq will decrease, Maj. Gen. Hussein Kamal, Iraq’s deputy Interior minister for intelligence affairs, said Monday.

“Al-Zarqawi or others have a terror agenda against the Iraqi people. This will not change by changing names and people. They will push ahead with their agenda,” Kamal said in a telephone interview.

In Baghdad, a U.S. military spokesman, Lt. Col. Barry Johnson, said the report about al-Zarqawi was “nothing we can verify.”

Al-Zarqawi's role questioned

Some experts have long cautioned that al-Zarqawi’s role may have been exaggerated and that some of the attacks claimed by his group — or that U.S. and Iraqi officials blamed on him — may have been carried out by others.

Iraq’s insurgency has always been made up of several disparate groups, and some of them, including Ansar al-Sunnah Army and the Islamic Army of Iraq, have been nearly as violent as al-Zarqawi’s al-Qaida in Iraq.

The Jordanian-born militant, however, seized most of the attention because of his relentless Internet propaganda efforts, the brutality of his attacks — including hostage beheading videos put on the Web — and a series of suicide car bombings that targeted mostly Shiites.

Then came a November triple suicide bombing against hotels in Jordan that killed 63 people, mostly Arab Muslims. That sparked a backlash against al-Zarqawi in Jordan, where there had been some sympathy for the insurgency. Even some fellow militants called for halting attacks on civilians.

In January, al-Zarqawi’s group said in a Web statement that it had joined five other Iraqi insurgent groups to form the Mujahedeen Shura Council, or Consultative Council of Holy Warriors. Since then, al-Zarqawi’s group has stopped issuing its own statements, a sharp contrast to its previous frequent postings, and al-Zarqawi has not issued a Web audiotape since January.

Instead, the Shura Council has put out daily statements listing its “operations” — including bombings of U.S. Humvees and trucks, shootings of Iraqi Shiite security forces and assassinations of Sunni Arabs cooperating with the government.

Barred from speaking publicly?

On Sunday, Huthayafa Azzam, believed to have close ties to Iraqi militants, told The Associated Press that al-Zarqawi had been confined to a military role within the coalition, specifically barred from making public statements and from any political or propaganda role.

It was not clear how Azzam, a son of one of Osama bin Laden’s spiritual mentors, had learned the information, which could not be independently verified. The claim by Azzam, a Jordanian of Palestinian origin, could also simply be a sign of squabbling among insurgent factions.

Azzam said Iraqis in the Shura Council had demanded al-Zarqawi give up his political role — particularly in propaganda — because he had “embarrassed” them with beheading videos and statements about regional politics and al-Qaida’s activities. Azzam said al-Zarqawi agreed and “pledged not to target Iraq’s neighbors, mainly his native Jordan, because that has harmed the Iraqi resistance’s relations with the Arab world.”

The political duties were handed over two weeks ago to the council head, an Iraqi called Abdullah Rashid al-Baghdadi, said Azzam.

Kamal, the deputy Iraqi interior minister, said officials do believe there have been meetings in the last few months between al-Zarqawi’s group and other groups, to unify efforts. He called it possible, but unknown, if those groups had rearranged their ranks and given al-Zarqawi a different assignment.

“After the losses they suffered in the west of Iraq and the popular anger against their presence, they could be trying to find an Iraqi facade,” he said, noting al-Zarqawi’s Jordanian nationality.

Kamal said he did not recognize the name of the supposed new political leader, Abdullah bin Rashed al-Baghdadi, and that it was probably a pseudonym.

Car bombings down

In the past few months, the number of multiple-death car bombings in Iraq — many of them suicide attacks — has dropped dramatically in a possible sign of either al-Zarqawi’s waning influence or a simple change in tactics.

Such bombings, identified with al-Zarqawi but also carried out by other groups, reached a high of 136 a month last May but fell to just 30 in December, 30 in January and 22 in February, according to statistics compiled by the Brookings Institution in Washington.

In contrast, the number of overall bombings, which also includes roadside bombs, is still running at high levels.

The U.S. military has attributed the drop in car bombs to its efforts to destroy several car bomb-making centers between Baghdad and the Syrian border.