The middle-age man with fever, cough and shallow breath told his doctor he had just returned to Northern California from a chicken farm in Vietnam.

That rang the first alarm bell.

Then came the initial tests from a local public-health laboratory: a positive result for influenza A, the virus family that includes bird flu. A swab from the man’s throat was rushed to the state lab in Richmond, where sophisticated tests yielded even more alarming findings — a strong likelihood he carried the deadly H5N1 strain.

“I need to talk to you,” microbiologist Hugo Guevara told Dr. Carol Glaser, chief of the virus lab.

The California Department of Health Services’ Richmond Campus has seen several adrenaline-pumping moments in recent months when it appeared bird flu had reached America.

The man was one of about three dozen Californians strongly suspected of being infected with bird flu who were tested here. About a dozen cases were “very worrisome” because of the patients’ travel histories and symptoms, Glaser said.

All tested negative in the end. Yet each case served as a practice run of sorts for the disease’s feared arrival.

“Because there are so many travelers into California, we could very well see a case tomorrow,” said Janice Louie, a medical officer at the lab.

The nation’s most populous state is uniquely vulnerable to the germ arriving via birds or people. Glaser and the lab’s assistant deputy director, Paul B. Kimsey, have bet a cup of coffee on which they think it will be.

Kimsey’s wager is with the birds. California has a $2.5 billion poultry industry, and millions of birds migrate along its flyways. Many experts, including the state’s top veterinarian, Richard Breitmeyer, believe those migratory routes could intersect with Asian bird migrations and bring the disease to California as early as this spring or summer.

Glaser is betting on the human path. Some 11,000 people arrive each day from Southeast Asia alone, officials say. Nodding her head at a map of the 54 countries and territories afflicted with bird flu, Glaser said: “I don’t even want to know the numbers” of people entering California from other regions.

At least 109 people worldwide have died from bird flu since outbreaks of H5N1 swept through Asian poultry populations in late 2003, according to the World Health Organization.

Health experts fear the H5N1 virus will eventually mutate into a form that spreads easily among people, potentially sparking a global pandemic. So far, the bird flu virus remains hard for humans to catch and spread among each other. Most cases have been traced to close contact with infected birds.

Testing 'hot cases'

Doctors in California have received urgent pleas from health officials to be vigilant about asking patients with certain symptoms about their recent travels. Did the patient visit a country with reported bird flu cases? Did he or she have exposure to sick poultry, or butcher a chicken?

The “hot cases” are those patients who have visited regions with reported cases of avian flu, and are sick within 10 days of returning. That sparks a chain of events that usually ends on Guevara’s computer monitor. The goal: to determine if the patient has garden-variety flu or bird flu.

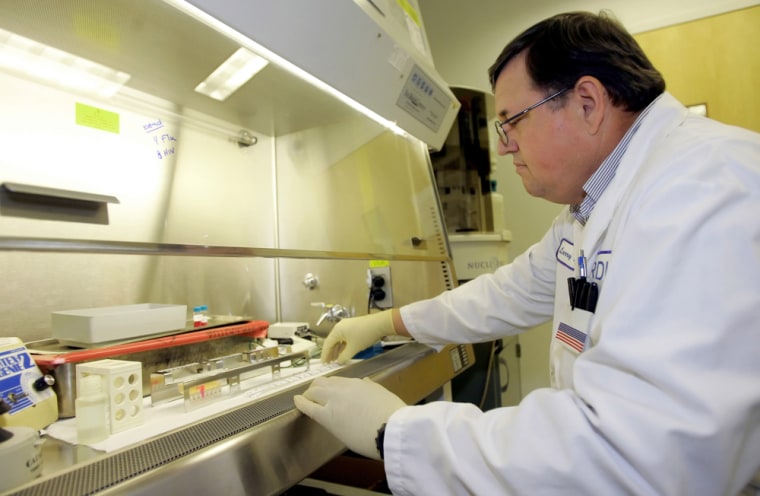

A sample is obtained by swabbing the patient’s throat or nose, then is shipped to a local laboratory that can determine whether a virus belongs to the influenza A family. Simultaneously, a second sample from the same patient is driven or flown to the Richmond lab, where it is greeted at the gate by a staffer who rushes it into testing.

In the hot cases, the patient goes into an isolation room during the testing to prevent any possible spread of the disease.

The Richmond facility northeast of San Francisco is a cluster of labs protected by motion-sensing gates, cameras and security guards. The testing sites are a warren of windowless rooms, their doors marked with “biohazard” warnings.

The lab can produce results in a matter of hours, as opposed to several days in less sophisticated facilities. The testing is too complex for hospitals or clinics to perform.

A confirmed case would set in motion an investigation into where the patient picked up the disease, and with whom he or she had had recent contact, said Dr. Howard Backer, California’s chief medical consultant for emergency preparedness. The state would step up surveillance aimed at detecting other cases, he said.

The objective would be to prevent a pandemic. That could trigger much more dire response, including quarantines and possible cremations of infected bodies, according to a draft version of the state’s response plan.

“Quick testing and getting results back from people who may be ill are critical,” said state Sen. Christine Kehoe, chairwoman of the Joint Legislative Committee on Emergency Services and Homeland Security. “Experts tell us the response has to be as quick and overwhelming as possible. We can’t let the flu get out in front of us.”