How can a mother avoid the same mistakes that her mom made? And how do you talk to a child about an absent father? Growing Up Healthy answers your queries. Have a question about children's health and well-being? E-mail the author. We’ll post select answers in future columns.

Q: I grew up with terrible self-esteem. My mother would tell me I was pretty but I never believed her because she was also very judgmental about appearance. How do I approach this subject with my own daughter so that she grows up with healthy self-esteem?

A: Your instincts are correct that what you say to your daughter now can influence how she feels about herself later. A study published last month in the Journal of Affective Disorder found that youngsters reared in hypercritical environments tend to become adults with exceptionally harsh internal self-critics.

“Children who have been raised in critical, verbally abusive homes are at risk as adults for an array of negative mental as well as physical issues,” says the study’s lead researcher, Natalie Sachs-Ericsson, a psychologist at Florida State University. “They’re more likely to suffer from low self-esteem, depression, anxiety and even heart disease as adults.”

Obviously, the worse the situation the worse the outcome. One negative comment won’t do it, but an environment filled with criticism might.

The trouble is, when it comes to mothers and daughters no subject is more fraught with possible problems (and criticism) than appearance, according to Deborah Tannen, author of "You’re Going to Wear That? Understanding Mothers and Daughters in Conversation."

Tannen, a professor of linguistics at Georgetown University in Washington, D.C., calls hair, clothes and weight “the big three” snags in mother-daughter communication.

“The mothers I interviewed said they feel like it’s a no-win situation when it comes to talking to their daughters about appearance,” says Tannen. “Daughters seem to look for any hint that a comment is critical.”

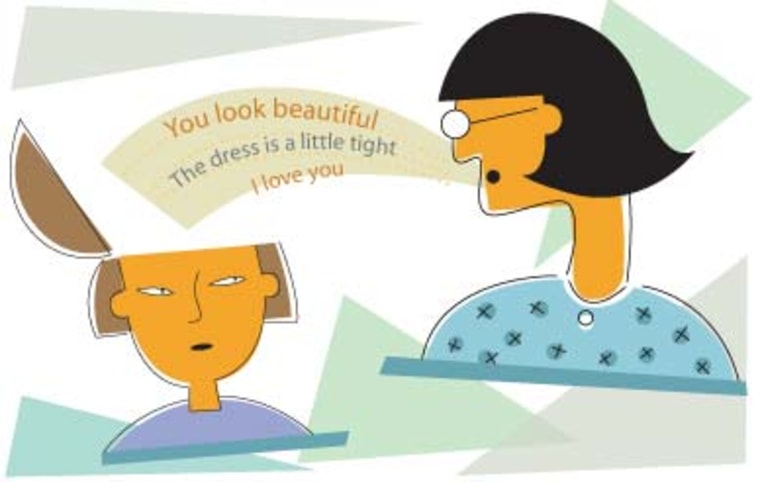

Maternal comments such as "Honey, your new dress is great! It makes you look so skinny," are often heard by daughters as "I’m fat," according to Tannen.

And why would this be? Probably because most mothers are critical — even if they don’t mean to be hurtful, says Tannen.

“Mothers are generally representative of society. They want what’s best for their daughters and they know women are judged on appearance,” she says.

Mothers also tend to turn the same level of scrutiny they reserve for themselves onto their daughters, according to Tannen. They feel they somehow owe it to their daughters to be brutally honest about appearance and steer their daughters to the choices that will make them look their best (in the mothers' eyes, of course).

“When I was researching my book I heard from so many adult women that their mothers put too much emphasis on appearance. They’d tell me, ‘She just wanted me to look good,’” says Tannen.

Remember, though, while beauty may be prized in our society, models and actresses generally are not known for their self-esteem. Bottom line is that if you want your daughter to have healthy self-esteem, steering the conversation away from her hair, weight and clothes is a good move.

“You should still tell your daughter that she’s pretty but over the long run the more important thing is try to get the focus off of appearance,” says Tannen. “Everything you say should reinforce the idea that appearance isn’t the main thing.”

So, be a nontraditional mom this Mother’s Day: compliment your daughter (or any other girl) on her ability to laugh loud, think sound, run fast and be a good friend.

Q: I am a single mom with an 8-month-old daughter. The father is not involved and probably never will be. How do I even begin to answer my child’s questions (when they do arise) about her biological father? How honest should I be?

A: Talking to your daughter about her biological father will be an ongoing conversation, says Andrew Roffman, a licensed clinical social worker at the New York University Child Study Center.

“You start early — as soon as she understands and asks a little bit — and then you talk about it regularly and probably in more detail as she gets older,” he says.

Don’t think you have to disclose everything all at once. Your daughter will probably not be mature enough to understand the complete scenario until adolescence. However, the very worst thing is not to talk about it at all, says Roffman.

“This leaves open the possibility for shame," he says. "A kid in this situation might jump to the conclusion that it was something about her or there is something terribly wrong with her father, something that reflects badly upon her.”

Hopefully, you can be honest with your daughter without demonizing or glamorizing her father and the situation.

And, even though your daughter is just an infant, there is something you can do now, according to Roffman, to get started on healthful communication. “You can start to work though your own feelings when it comes to the father,” he recommends. You may harbor negative feelings toward the father — anger, shame or even guilt about getting pregnant and the fact that he’s not a part of your life.

“Sometimes it’s helpful to talk to other single mothers or get some counseling,” says Roffman. Consider working with a therapist or seek out single parent support groups in your area.

In fact, the more support you have the better. “One of the key elements of building a strong family in single parent households especially seems to be reaching out and finding these support structures,” says Barbara Fiese, a professor of psychology at Syracuse University. “You create an extended family not just out of family members but also friends, support groups, church groups or neighbors.”

Fiese, who researches family traditions, also says that structure and ritual add stability to any family configuration — and benefit children.

“Rituals provide a sense of community, predictability and order. They’re a safe refuge from the hectic activities of the outside world. Something as simple as maintaining a bed-time ritual or eating meals together a few times a week can have a strong impact on any kid’s emotional and physical health,” says Fiese.

Victoria Clayton is a freelance writer based in California and co-author of "Fearless Pregnancy: Wisdom and Reassurance from a Doctor, a Midwife and a Mom," published by Fair Winds Press.