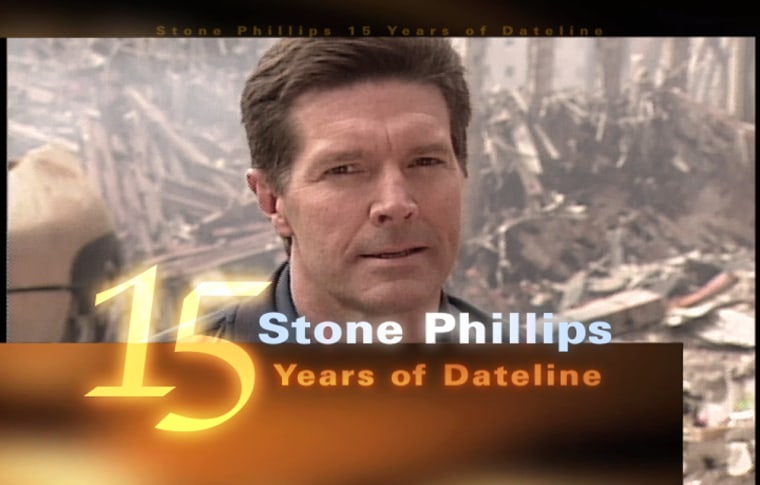

I want to take you back to some of my favorite stories from the past 15 years.

Judging from your letters and e-mails, the stories that have stayed with you over the years are about people facing immense challenges and finding the kind of inner strength we all wish we had.

As my time here at Dateline draws to an end, that's where we begin.

PROFILES IN COURAGE

"Lucky," 2005

Melissa Etheridge: It's the closest to death I have ever been. The chemotherapy takes you as far down into hell as you've ever ever been. Yeah.

Melissa Etheridge took her battle against breast cancer to the stage

Etheridge: I had such a good time at the Grammys

Her heroic performance at the 2005 Grammys turned a Janis Joplin classic into an instant anthem for breast cancer survivors everywhere.

Stone Phillips:Are you surprised by the impact it had? How it moved people? Etheridge: Yes. Yes, I'm definitely taken aback. And I remember when I finally made the choice. ‘Yeah, I'm going to do it bald, and you know what, maybe this will help somebody who's sitting on chemo, laying in bed, and going "God, I'm bald, isn't this weird?" Maybe it will help them feel a little better.'

As exhausting as the performance was, for Melissa it was music as medicine.

Etheridge: To be able to throw my head back and scream the last six months out of me, I'm completely grateful for that. Stone Phillips: Well, here's to healing and here's to the healing power of rock and roll.Etheridge: Oh yes, that's for sure.

"Tools for Life," 2001Robert Tools made medical history when he volunteered to receive the first fully implanted artificial heart. It was highly experimental.

Stone Phillips: Give us a report. How's the man and how's the machine? Robert Tools: Machine is fine. The man is fine. It works.

Doctors said if the 59-year-old former marine lived 60 days with his bionic heart, it would be a major success. When his story aired on Dateline, it was day 123 and counting.

Stone Phillips: You're eating hamburgers. You're drinking milkshakes. Tools: I enjoyed the first heart, but I'm going to enjoy the second heart even more.

With spirit as irrepressible as his appetite, Bob Tools was living for the moment - even as he was fighting for his life.

Stone Phillips: Why do you think they picked you? Tools: the doctors say I seem like a fighter, I refuse to give up.

"Soldier in the War," 1992Tennessee Curtiss was seven years old and so petite, but her courage was enormous.

Stone Phillips: Do you know that you're a very important person?Tennessee Curtiss: Mm-hm.Stone Phillips: Why do you think you're an important person?Tennessee Curtiss: Because I have cancer.Stone Phillips: What kind of cancer do you have? Do you know?Tennessee Curtiss: Neuroblastoma.Stone Phillips: What do you know about neuroblastoma?Tennessee Curtiss: It's just cancer cells. That's all it is.

With no hope of beating her own deadly cancer, she was taking experimental drugs in hopes of someday helping others.

Stone Phillips: Is it true that you have a boyfriend here at the hospital?Tennessee Curtiss: Yep. He's redheaded and he's my age.

How could any boy resist? Tennessee had already planned her own funeral. She wanted to be buried in her pink dress. But she never stopped talking about her dreams.

Tennessee Curtiss: I want to be a ballerina, tap dancer, cop or a doctor.Stone Phillips: You're going to have to make up your mind. You can't be all of those things.Tennessee Curtiss: I can't--I can't make up my mind, but--later on, I'll make up my mind right quick.Stone Phillips: Good luck, kid. Good luck.

"Die Hard" 2000At age 78, Frank Bigelow had had more near trips to the hereafter than anyone you'll ever meet.

Frank Bigelow: I got run over by a train when I was 20 months old.Stone Phillips: And you survived?Frank Bigelow: I'm still here.

His encounter with a Great Northern freight train was just the beginning. A Navy veteran of World War II, Frank survived the Bataan death march, disease in one Japanese POW camp, and a near beheading in another -- not to mention the makeshift amputation of a leg without anesthesia.

Painful as it was, Frank credits the fellow prisoner who performed the crude operation with saving his life.

Frank Bigelow: He had a hacksaw blade, and a razor blade, and he had some knives. And I asked him before he started operating on me, “Doc you got a drink of whiskey and a couple of aspirins you could give me?” He said “If I had ‘em, I'd take ‘em myself.” He was one of the finest men and finest doctors that ever lived and I'll never forget him for it.

His next close call came on August 9, 1945. Still a prisoner of war, Frank looked across the bay from Japan's Camp No. 17 to the city of Nagasake. And what caught his attention?

Stone Phillips: You saw the mushroom cloud?Frank Bigelow: Yeah, we saw it. Right under it.

Gazing at a war memorial he helped build in his community, Frank Bigelow felt blessed. His service and sacrifice was just part of being an American.

Frank Bigelow: That flag means a great deal to me. I fly it at home every day of my life. I salute that flag every night before I go to bed.Stone Phillips: It's a hell of a thing you've been through.Frank Bigelow: Yeah, but I sure thank God every day of my life for being right here. Every day.

"The Miracle of Ladder Company Six," 2001

Tommy Falco [firefighter]: I just heard the rumbling and the shaking. And I imagine we got knocked down the stairs. And I just remember laying down and, 'OK, this is it, you know. What's it going to feel like?' And I said, 'This is how it ends for me.' Sal D’Agostino: In the stairwell, after I got blown backwards and found my helmet, I said a Hail Mary. And it's the only prayer I ever really remembered. 'Sweet Jesus protect me and forgive me of my sins.' Matt Komorowski: An hour or two into the whole thing, I started seeing light at my feet. It was dim at first, and then all of a sudden, a beam of light shone at my feet. And that was hope that the outside was still there.

On September 11, the firefighters of Ladder Company Six had raced into the the hell that was the World Trade Center. On the crew were driver Mike Meldrum, a 20-year veteran; Sal D'Agostino, son of a retired firefighter; Tommy Falco, 18 years on the job; Matt Komorowski, 12 years; Bill Butler, the company's strongest man; and leading them that day, the first man into a fire, and the last one out, captain John Jonas.

And this woman will tell you they are all heroes.

Harris: When I was scared, they held my hand. They took off their jackets and gave them to me when I was cold. They told me not to be afraid, they would get me out, and they did.

Josephine Harris, a grandmother from Brooklyn, had been making her way down from the 73rd floor of the second tower. She was so tired she could barely take another step, when she came upon the men of ladder six.

Jonas: Billy's my biggest, strongest guy. I said, 'Billy, just put her arm around you and just--we'll do the best we can.' Butler: She seemed like she was scared. And I just--I said, you know, 'What--what's your name?' And she said, 'My name is Josephine.' And I said, 'Well, Josephine, we're going to get you out of here today.'

Progress was painstakingly slow. Then they reached the fourth floor.

Jonas: That was when Josephine couldn't, she said 'That's it, I can't go anymore.’Stone Phillips: So she stopped there?Jonas: She stopped at the fourth floor.

At that moment, the building came crashing down. Miraculously, they were still alive. And reporting from the scene, I was astounded to see just how lucky they were.

They were scattered along what was left of the stairwell between the second and fourth floors; their small pocket of safety was one of the few spaces in the building that wasn't crushed in the collapse. As workers continued to clear away the rubble, you could actually see it.

By stopping on the fourth floor, Josephine Harris had saved herself and the men of Ladder Six.

Stone Phillips: Do you all believe that she is the reason you're all here? Komorowski: Mm-hmm. Yes. Meldrum: Definitely. Tommy Falco: Definitely. Sal D’Agostino: Yeah, I do. Stone Phillips: If she hadn't stopped at that point in that stairwell... Meldrum: It was her just picking, I guess, just the right spot. It was--it was her time to say, 'Guys, this is where we're going to make a stand,' I guess she's like our guardian angel. She must have been sent to us for a reason.

Harris: They are magnificent.Stone Phillips: You know what they say? They say you are their guardian angel. Harris: If it wasn't for them, I wouldn't be here today. I would not be sitting here.Stone Phillips: How do you begin to thank them?Harris: I don't know what else to do except give them a big hug

Two days after the interview, she did.

It was the first day they'd seen each other since that day of incomprehensible horror and unparalleled bravery.

Komorowski: Thank you for saving our lives. Harris: Oh, thank you for saving my life. Komorowski: God bless you, ma'am. Harris: You too. Komorowski: God bless you. Harris: Bless you.

STAR TURNS

Ellen Degeneres, 2004

Stone Phillips: You exude so much positive energy on the show. Where does that come from? Ellen DeGeneres: The liquor. I'm sure of it.

If at first you don't succeed, try again. It was a theme of Ellen Degeneres' career -- and my interview.

Stone Phillips: Your humor has always been good-natured and--and clean. Ellen DeGeneres: Mm-hmm. Stone Phillips: Have you ever been tempted to work blue? Ellen DeGeneres: (BLEEP)...no. Stone Phillips: (Laughs) Let me ask that question again. Ellen DeGeneres: All right. Stone Phillips: Have you ever been tempted to work blue? Ellen DeGeneres: I'll...(BLEEP)...say it again.

Michael Caine, 2000

Michael Caine: I would never do that because I think that looks ridiculous.

A dead serious Michael Caine was explaining his disdain for nude scenes, when suddenly the academy award-winning Brit began to chuckle.

Michael Caine: I always remember they said to Robert Halpman, who was the boss of the Royal Ballet here, they said, 'Have you ever thought of doing a nude ballet … in the nude?' So he said, 'No, never.' So he said 'Why not?' He said, 'Because not everything stops when the music does!' And that's how I feel. (laughter)

Sandra Bernhard, 1992

Sandra Bernhard: If you can save one straight man from being a complete sexist, you know, idiot -- I mean I think that's like a great thing to do.

Leave it to Sandra Bernhard to pose for Playboy and call it a public service, exposing a whole new audience to her un-bunny-like appearance, unrelenting sarcasm and unabashed lesbianism.

Stone Phillips: If you wind up with another woman and you want children?Sandra Bernhard: 'Another woman'?Stone Phillips: Another woman, and you...Sandra Bernhard: Are you suggesting that I just left one?Stone Phillips: you're one woman, and they would be the other woman.Sandra Bernhard: You mean 'a woman.'Stone Phillips: 'A woman.' If you wind up with a woman...Sandra Bernhard: Yeah.Stone Phillips: ...and you want kids, would you...Sandra Bernhard: Sure.Stone Phillips: ...would you do artificial insemination...Sandra Bernhard: Yeah, I have a lot of friends who would, you know, throw some sperm my way. Hey, while you're at it, save some for me. Stone?Stone Phillips: Oh please!

Howard Stern, 1993

Howard Stern: Ah, mother -- see I have a mother, isn't that great? Satan has a mother.

Shock jock Howard Stern wasn’t at the mic but at home with his family.

Howard Stern: Nice to see you, you handsome devil.Stone Phillips: Don't start with me Howard!

Actually, I was the one who started with him -- with a few questions at the dinner table for Howard's then-wife Alison.

Stone Phillips: When Howard starts talking about your private life--your sex life, does that embarrass you?Alison: Sometimes it gets to me. It depends. You know, some--certain things are exaggerated and certain things taken out of context. But you know, I let him have a good time with it.Howard Stern: What are you looking at me for? (laughter)

But Howard may have gone too far when he talked on the air about Alison's miscarriage.

Alison: I think I just assumed it was a private incident in our personal life.Howard Stern: I don't apologize for anything I've ever said, and I don't regret anything I've ever said.Stone Phillips: Do you regret having hurt anybody's feelings?Howard Stern: I don't think I regret it, no. I don't. I don't think I do.Stone Phillips: You hurt your wife Alison … I think when you talked about the miscarriage, don't you?Howard Stern: At the time, it did hurt her feelings. And I guess I really didn't understand why she felt so bad about it. And that's my failure, I guess, as a human being.

Chris Rock, 2004

Chris Rock: Marriage is beautiful. But if you think you're going to hold onto your individual self, you're an idiot. Stone Phillips: If you're a guy. Chris Rock: If you're a guy, that part of you is dead.

Chris Rock was riffing on marriage. He was seven years into his.

Chris Rock: Take yourself to the door and wave, 'Hey, see you later.' You don't walk around the house like you're Stone Phillips. You're 'Her husband.' That's it.Stone Phillips: I know that, I guess the sooner we realize that, the better off we are.Chris Rock: Hey, if bin Laden was here right now, he's going, 'Oh, yeah, my eight wives are killing me, too.'

He also revealed the childhood pain that fuels some of his brilliantly biting humor.

Chris Rock: When I was bused to white school, I basically became a hermit, it killed a part of me. I retreated into myself. Stone Phillips: What kind of things did you experience? Chris Rock: Being a skinny kid is going to get you beat up anyway. You know, you just--even if I was white, I would probably gotten my ass kicked every day. But being black, and being one of the only black boys in --in my grade. You're dealing with ‘nigger this, nigger that.’ I mean, I'm not going to dwell on it now. I think I won, you know.

Eva Longoria, 2005

Eva Longoria: You don't have an apron, but I only have one.Stone Phillips: You know, I don't plan to really get that dirty as a matter of fact.Eva Longoria: Oh, no, you are, you're going to get dirty.

Eva Longoria looked glamorous during our interview, even in the kitchen. But surprising as it may seem, she told me it wasn't always that way.

Eva Longoria: I grew up as the ugly duckling. They used to call me "la prieta faya,” which means "the ugly dark one." Because my... Stone Phillips: That is hard to believe. Eva Longoria: Yeah, I know. People would literally walk up to my mom when we were little and they--they would go, “Oh, my God! Your daughters are so beautiful. And who is this?”

That's before she became a cover girl, one of TV's Desperate Housewives and NBA star Tony Parker's biggest fan.

Stone Phillips: Do you want to get married? Eva Longoria: Yes. Absolutely … I want the engagement and the wedding and the kids and the family. I'm desperate to be a housewife.

Salma Hayek, 2003

Stone Phillips: Tell me about the tango scene [in Hayek’s movie “Frida”].Salma Hayek: Look at your face change, Stone. You have been looking at me with one face the whole interview.Stone Phillips: Ok. Ok.Salma Hayek: You--you go--and all of a sudden you go, `Tell me about the tango.'Stone Phillips: Just--just please tell me about the tango scene, Salma.Salma Hayek: And your face completely transforms.

The scene was from “Frida,” the Oscar-winning movie that Salma Hayek produced and starred in.

Salma Hayek: I've got to say, you know you're not gay when you kiss Ashley Judd, because she has the most amazing mouth. It's soft, she's such a great kisser, and you don't get butterflies in your stomach.Stone Phillips: No thrill.Salma Hayek: No. You just sort of giggle and say, `Ooh hoo! We kissed in the mouth.’

Jack Black, 2005

Jack Black: This is the story of a guy who has a deep and powerful spiritual side, but he also has a side where he wants to kick ass and be a powerful wrestler hero. I'm thinking Oscar.

He was thinking Oscar, but Jack Black was also sporting a black eye from a stunt gone bad on the set of "Nacho Libre.”

Jack Black: At first I was scared that I was going to lose this power (moves eyebrows) and then I thought, 'Oh, no. I didn't insure the eyebrows!' Stone Phillips: (Attempting to move eyebrows) How do you... Jack Black: How do you do it? Stone Phillips: You can do both of them. Jack Black: Yeah, this--this is how you do it. You go both of them up... Stone Phillips: OK. Jack Black: ...and then just focus on getting one down. Yeah, you got it. Stone Phillips: Well, there's one. Jack Black: Yeah. Stone Phillips: But see, I can't the... Jack Black: The other one--well, my other one is not as good. I'm not going to lie to you.

After the brow beating, he made nice with a little song he wrote for me. He sang, "Stone Phillips, more than meets the eye” and said “’Cause I think there's more to you than meets the eye. It needs a second verse.”

Glen Campbell, 2004Glen Campbell played one of my all-time favorites, but it was another instrument that brought me to his home.

A court ordered breathalyzer is required to start his car. He'd just been released from jail after a drunk driving accident and a belligerent encounter with police.

Stone Phillips: Do you remember anything about what happened at the police station? Glen Campbell: Mm-hmm. Stone Phillips: I mean, do you remember shouting and cursing and... Glen Campbell: No. Stone Phillips: ...and kicking?Glen Campbell: No. I don't. Stone Phillips: But you don't doubt that it happened?Glen Campbell: No, I don't doubt that it happened. I had no control whatsoever of it. That's what scared me -- during the total blackout I have no idea what I did. You know, you could have killed somebody. You could have--and I would have never known it … It happened for a reason and I think it was, to you know, slap Glen Campbell in the face and kind of wake me up a little bit.Stone Phillips: Has it done that?Glen Campbell: Yes, it definitely has.

Sophia Loren, 1999

Stone Phillips: Do you think of yourself as sexy?Sophia Loren: Well, to be a sex symbol, as they say, symbol? I think that I like that very much. I always liked to seduce and to be seduced, as a matter of fact. Yes, I think it's fun.

At Sophia Loren's home in Geneva, Switzerland, we cooked and she reflected on her life and loves and one of the many suitors she turned down -- Cary Grant.

Stone Phillips: He fell in love with you.Sophia Loren: Yes.Stone Phillips: Is it true he proposed?Sophia Loren: I think he did, yes.Stone Phillips: That's an offer a lot of women would not have been able to refuse.Sophia Loren: I know. I've always been afraid that what I felt for Cary was something that, because I was very young, it was just infatuation. I was afraid to make a mistake, for me and for him.

But there was no mistaking the chemistry with one grumpy old man, the late Walter Matthau.

Sophia Loren: He's my last love, Walter Matthau. When we met, there were fireworks in the room. Everything was going on. Everybody was laughing. And they knew that we connected right away. I don't know why, but it just happened. Stone Phillips: You looked like you were having fun.Sophia Loren: We were having fun. And most of all, he was having a great deal of fun.

CRIMINAL MINDS

Bernhard Goetz, 1996

Bernhard Goetz: Society is better off without certain people. The people, whether they're--whether one believes that they should be killed or--locked up, or used in forced labor, is just a matter of one's political point of view.

He is blunt and controversial. He is hailed by some as a hero, vilified by others as a vigilante.

His name is Bernhard Goetz, the so-called subway gunman of New York City, the man who shot four black youths in a subway car because he believed they were about to mug him.

Stone Phillips: You describe this as a mugging, but no one pulled a knife on you. No one raised a fist against you.Bernard Goetz: That is correct, but by words and by deeds they gave me every indication that they were about to use force on me.Stone Phillips: Are you surprised that you were as competent with that weapon as you were?Bernard Goetz: That did surprise me at the time. But when I was a young boy, I used to play cowboys and Indians a lot with cap guns.Stone Phillips: So cowboys and Indians was a--was a warmup for this?Bernard Goetz: Oh definitely. It's--it's a way of teaching a person how to shoot a gun. To shoot a gun proficiently, including speed shooting, is much less of a skill than typing.Stone Phillips: Yeah, but we're talking about a real gun, real bullets, and real people.Bernard Goetz: Easier than typing.

After shooting and paralyzing one of his victims, Goetz didn't think twice about taking aim again.

Bernard Goetz: He was moving around, and I just tried to shoot him a second time.Stone Phillips: He was trying to get away from you.Bernard Goetz: Well, I didn't know that.Stone Phillips: Were you more afraid because they were black?Bernard Goetz: Possibly, yes.Stone Phillips: Are you a racist?Bernard Goetz: I don't believe so.Stone Phillips: Have you ever used ‘the N word’?Bernard Goetz: It's something that's in bad taste, but yes I have.Stone Phillips: "Their mothers should have had abortions."Bernard Goetz: I said that to one reporter. I think that would have been a better solution, just like one practices population control with animals.Stone Phillips: Is that what you were doing on the subway that day when you opened fire, getting rid of what you considered to be undesirable elements?Bernard Goetz: Well, no. The fact that I may, well almost got rid of some undesirable elements I think, you know, it was something I wasn't looking for.Stone Phillips: Do you think what you did was a public service?Bernard Goetz: What I did I'm not ashamed of at all. And perhaps that's a good way of looking at it, as a public service.

Jeffrey Dahmer, 1994

Jeffrey Dahmer: He was hanging over the side of the bed. And I have no memory of beating him to death, but I must have.

Chilling words from a serial killer in what turned out to be Jeffrey Dahmer's first, and only, network television interview.

When I met Dahmer and his father in this maximum security prison, he vividly described -- in the most matter-of-fact way -- the gruesome impluses that drove him to kill and cannibalize 17 young men. He told me it began with a bizarre childhood fascination with dead animals and a teenage compulsion to dissect them.

Stone Phillips: Was there some pleasure in--in the cutting open of the animal?Jeffrey Dahmer: Yes. There was. No--no sexual pleasure, but just--Stone Phillips: Sense of power, sense of control?Jeffrey Dahmer: I suppose that's a good way of putting it, yeah. I suppose it could have turned into a normal hobby like taxidermy, but it didn't. It veered off into this. Stone Phillips: Was it the killing that excited you or is it what happened after the killing?Jeffrey Dahmer: No, the--the killing was just a means to an end. That--that was the least satisfactory part. I didn't enjoy doing that. I had this recurring fantasy of meeting a hitchhiker on the road and of taking him hostage and doing what I wanted … Lust played a big part of it. Controlling lust. Stone Phillips: Why the cannibalism?Jeffrey Dahmer: That was--that was another step. It--it made me feel like they were a permanent part of me … Besides the just mere curiosity of what it would be like it gave me a sexual satisfaction to do that.Stone Phillips: Is it still there … Does it ever go away?Jeffrey Dahmer: In part. No, it never--it never completely goes away. I wish I--there was some way to completely get rid of--of the compulsive thoughts, the feelings. It's not nearly so bad now that there's--there's no avenues to actually act on it. But no, it never seems to go completely away.Stone Phillips: So the thoughts still come to you?Jeffrey Dahmer: Sometimes, yeah.

ECHOES OF WAR

"The Long Way Home,” 1995

Judy Warstler: Even to this day when I hear a Rolling Stones song on the radio, I instantly think of him.Gary Warstler: That's one thing I've always wanted to do is to look into his eyes and see what I'm going to be like in 20 years. Who am I going to look like?

Gary Warstler was two years old and his sister Judy just a newborn when their father shipped out to serve his country in Vietnam. Their father didn't come home.

Private George Warstler disappeared. It was a mystery the Army couldn't explain and neither could Gary and Judy's mother.

Gary Warstler: She couldn't explain it. She couldn't tell us what happened.Stone Phillips: Did you consider him missing, or did you consider him dead?Judy Warstler: I considered him gone.

After 12 years, the military finally pronounced George dead. But the death certificate only raised more questions.

It said George had not died in battle, but from unknown causes, and the last place he'd been seen alive, in 1969, was not Vietnam, but Sydney, Australia.

Gary Warstler: The man wasn't in Vietnam. That's when it all started. That's when you started like, 'Well, maybe he's alive. Maybe he's not dead.'

So the searching began. Off and on for the next 13 years, Gary contacted MIA and veterans' groups, but could find no trace of his father. Then in February 1994, 25 years after George Warstler was supposed to come home, his wife Gisela got a notice in the mail that the family's death benefits were being cut off.

Stone Phillips: That's how you found out that your husband was alive?Gisela Warstler: That's right. My first reaction was shock, then somewhat of relief, and then some terrible anger set in.Stone Phillips: Angry that he had...Gisela Warstler: Angry that he let us hang like this for 25 years. Gary Warstler: She said, 'Your dad's alive.’ And ah, I didn't believe her. I said ‘Come on.’Judy Warstler: It was like finding the missing piece of the puzzle that you've been searching for your whole life.

And where was George Warstler? Gary tracked him down, half a world away. Don't let the name on the hat or the lawn bowling fool you. David Mitchell of Wellington, New Zealand was really George Warstler of Ashley, Indiana.

Stone Phillips: What is it like to be found?George Warstler: Frightening. Very frightening.

He had walked away from his country, his name and his family. After two tours in Vietnam, George had spiraled into what he called his ‘going down.’

Stone Phillips: Did you see people get killed?George Warstler: Yes.

Even after a quarter century, his memories of the war and of one mission in particular were still overwhelming. In a midnight ambush that went terribly wrong, he had lost his best friend.

George Warstler: He didn't get killed on the spot, but we to lift him into the helicopter and I remember his leg coming off in my hand. I was laying right beside him and I never got a scratch, I'll never understand that.

But it's what happened next that pushed him over the edge. After volunteering for his third tour, George was in Australia for rest and relaxation when he heard that a dozen soldiers in his platoon had just been killed.

George Warstler: That's when I think, ‘Well I should have been there with them. I shouldn't be over here.’ I think that's when the decision came to disappear.

For 25 years, living under a false name, George never called, never wrote. Now, he was about to face everything he'd been running from for so long. Gary had come to New Zealand to meet a stranger.

In 1969, a little boy had looked up to his father. Today, his father was looking up to him.

George to Gary: I can't get over how tall you are!

As for the question: why his dad never came home?

Stone Phillips: Have you asked him why?Gary Warstler: Nah, and you know to be real honest with you it's not important. This is the second chance I've got, and there's just a million people that like this second chance that I've got, so it doesn't matter.

Then it was George's turn to travel. He returned to the United States to get square with his former wife, who forgave him; with the Army, which granted him an honorable discharge; and with the daughter, who had waited a lifetime to meet him.

Judy Warstler: I think it's going to take a lot of courage to come back home to us after so many years when we know that he doesn't have to do this.Judy Warstler: I've been waiting forever. It seems like forever for this. I think my heart's beating so fast right now. George Warstler: Hey, Gary. Judy Warstler: Hi. George Warstler: How have you been? Judy Warstler: I'm so happy to finally meet you. (hugs and tears)

Although George would return to his home in New Zealand, he was finally home from the war.

"Going Home," 1997

Waxahachie, Texas. The farm where my father grew up. The place he left behind when he went off to war.

Stone Phillips: How did you feel about going into war?Dad: Well, I was--I was frightened and I wondered--I could just visualize what ha--would happen if I took a shell burst right in my chest.

In Belgium, on January 8, 1945, my father was hit--one of more than 60,000 American soldiers killed or wounded in the battle of the bulge. Shrapnel from a German artillery shell slashed and nearly severed his right arm.

Dad: I thought--I thought my arm was blown off … it's just no feeling.

Dad spent the next three years in and out of Army hospitals. But his right arm would be paralyzed for life.

It's ironic, but actually my father found in his paralyzed arm some relief from a handicap he always considered far more debilitating--his paralyzing shyness.

Dad: If anything, I say it was a help, in that...Stone Phillips: Because you were self-conscious and shy to begin with and this sort of...Dad: Yeah. And without a reason, perhaps, you know.Stone Phillips: And this gave you a reason.Dad: It did.

Though there were many things he had trouble doing, Dad never stopped trying. As unnatural as it may have felt, Dad threw a decent left-handed spiral. He taught me to throw, and I became a quarterback back in high school--even got the chance to play in college.

The Yale Bowl seats 70,000 people but I always played for an audience of one.

Stone Phillips: I realize today, looking back on it, that--that I needed to play football. I needed to because I needed to try to make it better for you.Dad: Yeah.Stone Phillips: I wanted the guy with the bad arm in the stands to see a good pass and be able to say, `That's my kid.'

As if throwing a good pass could really have made things better for him.

Dad: Unexpected kindness. It's--it's devastating. (crying)Stone Phillips: It's paradoxical, I think, that the--the disability that I wanted so desperately to make better for you wound up making me better. Because I--I--I strove more, I worked harder, I practiced more.Dad: You did.Stone Phillips: And in a--in a sense, it winds up being a--a gift from a--from a parent to a child, I think. I think it certainly has been that for me. And I don't know whether to thank you or to say I'm sorry. I guess I should say both. Dad: I should say thank you.

A retired chemical engineer, my dad survived not only the battlefields of Europe, but open-heart surgery and a major depression. So the challenge of joining the computer age has been relatively easy--though at times, it can be a stretch.

The other keyboard he leaves to my mother, a Dallas girl who read the first letters he wrote left-handed as she waited for him to come home from the war. Though his hugs would never be quite the same, she married her farm boy from Waxahachie in June 1945. Together they raised three kids in Texas and later at our home in Missouri.

Going home to interview my father helped me get a little more comfortable with some uncomfortable feelings, comfortable enough to tell him something I should have told him long ago.

Stone Phillips: I think you have shaped my life more than you know. You talked about your emotional struggles, the depression. I think I tried to be cheerful as a result.Dad: Yeah, I suppose so.Stone Phillips: I think as a result of your--of your bad arm...Dad: You wanted to compensate -Stone Phillips: I went into sports. And because of your shyness, being a farm kid, I went on television.Dad: Yeah. Well, one thing I will never do is go on television. Stone Phillips: Well, thanks.Dad: Sure.Stone Phillips: Thanks--thanks for doing this interview. I love you, Dad.Dad: Well, I love you, son. Thank you.

He had a lot of good soundbites, as we say in the business. And one came to mind as I thought about how to wrap this up.

"No matter what happens on the field, or in life," he told his players, "the most important play is always the next play."

To all of you who have shared your stories, it's been a privilege. To all of you with stories yet to tell, stay in touch. To all of you who have tuned in over these past fifteen years, I hope, in some useful, positive way, the stories that reached you, touched you.

I'm Stone Phillips.

Thanks for watching.