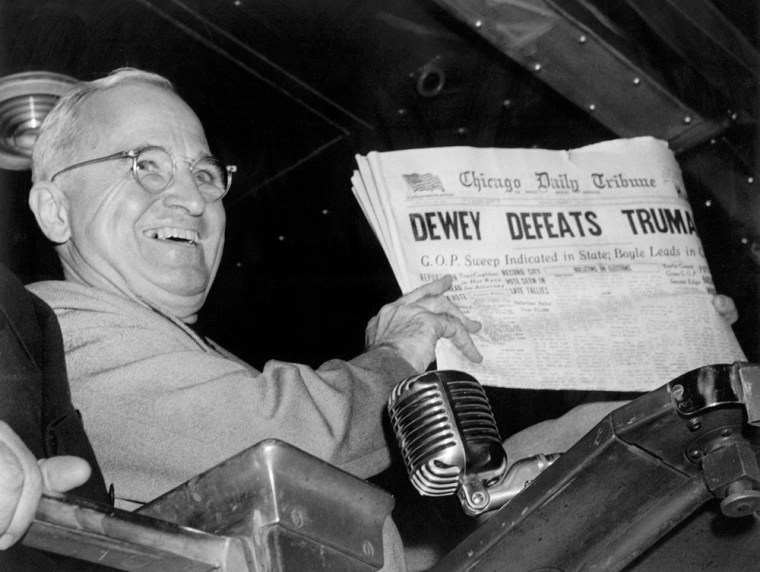

“Dewey Defeats Truman.”

It’s perhaps the most famous headline in newspaper history — famous for being so spectacularly wrong.

Harry Truman held up the Nov. 3, 1948 edition of the Chicago Tribune with that headline as he celebrated victory.

Of course, it was Truman who defeated Dewey, although almost no one had expected him to win.

Truman, the scrappy politician from the Kansas City machine of Boss Tom Pendergast, had been elevated to the vice presidency and then suddenly became president of the United States when Franklin D. Roosevelt died on April 12, 1945.

The loser: Republican Thomas Dewey, the governor of New York, the man all the polls projected would win.

On Election Day, Truman won 28 of the 48 states and 303 out of 531 electoral votes.

But considering that his party was in a shambles as the campaign started, how in the world did Truman pull off his victory?

Democratic fratricide

By midsummer 1948, Truman’s party appeared to have committed fratricide.

On the left was Truman’s predecessor as vice president, Henry Wallace, running on the Progressive Party ticket.

Roosevelt had dumped Wallace from the ticket in 1944, but given him a consolation job as Secretary of Commerce.

Truman forced Wallace to resign in 1946 after he gave a speech attacking the president’s unyielding policy toward the Soviet Union.

In a disdainful letter of resignation, Wallace wrote to the president:

Dear Harry,

As you requested, here is my resignation. I shall continue to fight for peace. I am sure you approve and will join me in that great endeavor.

Respectfully yours,

H.A. Wallace

Wallace’s Progressive Party platform denounced “anti-Soviet hysteria” and “militarism” and called for federal ownership of banks, railroads, the aircraft industry and electric utilities.

Communists as 'Christian martyrs'

Not a Communist himself, Wallace was sympathetic to them. “The communists are the closest things to the early Christian martyrs,” he said during the campaign.

“In the end, the Wallace vote threw only three states to Dewey, far fewer than we originally feared,” said Truman political adviser Clark Clifford later. The three states were New York, Michigan and Maryland.

But “there was an unanticipated dividend from Henry Wallace’s participation in the race,” Clifford said. “His attacks on President Truman for being too tough on communists helped protect the president from Republican charges that he was too soft.”

On Truman’s right stood South Carolina’s governor, Strom Thurmond, leading the States Rights Democrats, or “Dixiecrats.”

Clifford advised Truman in January of 1948 that the election would be decided by urban black voters in New York, California, Illinois, and Ohio. Truman ended up winning all but New York, Dewey's home state.

Bold civil rights agenda

Partly to appeal to black voters, Clifford urged Truman to submit a bold civil rights agenda to Congress, including an anti-lynching bill and an end to racial segregation on interstate trains, buses and airplanes.

Truman followed Clifford’s advice. “The Negro votes in the crucial states will more than cancel out any votes the president may lose in the South,” Clifford predicted, and he was probably right.

Thurmond was defiant as he launched his campaign in Birmingham, Ala.

“There’s not enough troops in the army to force the Southern people to break down segregation and admit the Negro race into our theaters, into or swimming pools, into our homes, and into our churches,” he declared.

Despite having the advantage of a divided Democratic Party facing him, Dewey proved to be a poor candidate.

“The bridegroom on the wedding cake,” actress Ethel Barrymore called him. Stiff, aloof, and self-confident to the point of complacency, Dewey campaigned far less intensely than Truman did.

One sign of his complacency: "Dewey, who had carried Ohio against Roosevelt in 1944, was so sure of carrying it again, he would not actively campaign there," said Truman biographer David McCullough.

It was if the roles had been reversed: Truman as the challenger and Dewey as the incumbent.

Truman barnstormed across the nation on his campaign train, travelling nearly 22,000 miles by Election Day, at one point giving 13 speeches in one day.

'Cold men... cunning men'

“These Republican gluttons of privilege are cold men. They are cunning men…. They want a return of the Wall Street economic dictatorship,” he told a crowd in Iowa. At a stop in Utah he attacked “bloodsuckers who have offices on Wall Street.”

Truman biographer David McCullough said that Dewey might have exposed the shallowness of this rhetoric simply by noting that Truman's cabinet members and advisors Averell Harriman, Robert Lovett, and James Forrestal had all been powerful figures on Wall Street.

Dewey also failed to pounce on a blunder Truman made in early October.

Without consulting his Secretary of State, Gen. George Marshall, the president decided to send his crony, Chief Justice Fred Vinson, a man with no expertise in foreign policy, to Moscow to chat with dictator Joseph Stalin in the hope of easing U.S.-Soviet tensions.

Clifford later called Truman’s idea “a mistake which could have cost him the election — had Dewey exploited it…. I was astonished Dewey did not….” After Marshall objected, Truman cancelled Vinson’s mission to Moscow.

On Election Day Truman kept just enough of the traditionally Democratic Solid South — all but four states — and the Farm Belt, as well as the Far West.

Dewey carried almost all of the Northeast, as well as his native Michigan and Indiana, and added four Great Plains states.

Wallace won only about two percent of the popular vote, but no electoral votes since his votes were widely scattered.

Thurmond’s votes were concentrated in the four Southern states he carried, giving him 39 electoral votes.

But Thurmond’s presidential bid was a harbinger of the rebellion of white voters in the South against the Democratic Party and especially against its civil rights program.

In 1964, Republican Barry Goldwater, running partly on his opposition to the Civil Rights Act of 1964, won the four states Thurmond had carried in 1948, plus one more, Georgia.

After 1948, Republican presidential candidates succeeded in making the South — which had been a Democratic stronghold since 1880 — mostly their turf.

In that way, 1948 was a major turning point in American politics.