Amy Wales: It hit me viscerally. The way that nightmares tend to. And I still cannot get my head around why that happened.

It was just three weeks after the attacks of September 11, 2001. America was on high alert. Amy Wales was in London when she had a terrifying dream about her father, back home in Seattle.

Amy Wales, Tom Wales' daughter: It looks sort of - very much like a terrorist attack in the domestic sense. And then more specifically, this cloudy figure shooting my father. And I woke up and I was screaming and was upset. And I immediately called him and left a message.

Sara James, Dateline correspondent: What did you say?

Amy Wales: I said, "'Pa. I dreamt you were shot. And, are you okay? Are you alive? You need to call me. And - I love you so much. And I am - I can't imagine it. I can't imagine it. Please call me back.'"

Hours passed and finally Amy’s phone rang.

Amy Wales: He called up and he was just laughing and clearly making light of the situation. And said, "No, I'm very much alive and don't you worry, and in fact, you and your brother will be arguing about what to do with me later in life. As I'm up to no good in a nursing home."

Amy, deeply relieved, went back to her routine as a graduate student abroad. But just a week later, another call — this time, from her mother. The nightmare had come true. Amy's father, Tom Wales, had been shot to death in his Seattle home.

Amy Wales: It was horrible. It was shocking - it was devastating. I certainly wasn't prepared for it.

What happened that October night would haunt his family and baffle investigators for years to come as they tried to figure out who'd killed Tom Wales — and why.

On October 11, 2001, after a full day at the office, Tom Wales returned here to his home in Seattle's Queen Anne neighborhood. He spent the evening as he often did, on the computer. At 10:40 that night, neighbors called 911 saying they'd heard gunshots. Seattle police responded immediately, scouring the crime scene. They discovered several shell casings but no murder weapon. The killer had shot Wales in the neck and torso - then vanished into the night.

To those who knew him, the murder made no sense.

Wales was beloved, both by his close knit family and a wide circle of friends who found him funny, engaging and delightfully quirky. He was a mountaineer who also tackled culinary peaks.

Ralph Fascitelli: Everybody that met Tom thought they were Tom's best friend. He had a dozen best friends.

Yet Wales also had an unknown enemy, someone who hated him enough to kill him with ruthless, anonymous efficiency. In fact, the murder looked so much like a "hit" that investigators wondered if the killer might be someone Wales had antagonized through his work because Tom Wales was an assistant U.S. Attorney. If that were the case, it would be the first time in U.S. history that a federal prosecutor was killed in connection with his work.

Mark Bartlett: A coward snuck behind his back and crawled into his backyard and shot him through a window, four, five, six times. It's beyond despicable.

Sara James: This is somebody who stalked him.

Mark Bartlett: It would appear.

Robert Westinghouse and Mark Bartlett are prosecutors who worked closely with Wales in the U.S. Attorney's office. Wales handled white collar criminal cases like bank fraud and embezzlement.

Robert Westinghouse: He put justice above everything else in his work. It made him an excellent prosecutor.

A federal prosecutor for 18 years, he had put hundreds of men and women behind bars. Could someone he'd prosecuted have shot him, or hired a hitman? A scenario difficult for his colleagues to accept. They say Wales was fair as well as tough, even earning the respect of many he prosecuted.

Robert Westinghouse: There have been a number of defendants that were convicted by Tom Wales who have written letters that express their gratitude for him and his treatment of them.

Still, there was one notable exception. Shortly before his death, Wales had prosecuted a pilot who was part-owner of a company involved in a complicated case concerning the sale of rebuilt helicopters. The pilot's company wound up pleading guilty to a misdemeanor. The pilot felt unfairly prosecuted and, in a rare move, sued the U.S. Attorney's office and singled out Tom Wales.

The FBI won't discuss any possible suspects. But Seattle Times reporter Steve Miletich has learned from law enforcement sources and people close to the pilot that investigators started looking at him soon after the murder.

Sara James: What do we know about the movements of the pilot on the night when Tom Wales was murdered?

Steve Miletich: we know that he went to a movie that night, 2001: A Space Odyssey, in downtown Seattle.

Investigators quickly realized that that movie theater was close to Wales' home. The pilot and his companion left the theatre in separate cars when the movie let out at about 9:30 p-m.

Steve Miletich: The shooting happened at 10:40. Tom Wales' house was about 10 minutes away from - from the movie theatre.

But sometime around 10:40, around the time of the murder, telephone records show a call was made from the pilot's home phone. It seemed the pilot, who lived alone, had an alibi.

Steve Miletich: His defenders will say that it does show that he could not have killed Tom Wales.

And so the ruthless, careful killer of Tom Wales - whoever he, or she, was - was still out there, in the shadows.

Wales (on tape): We will never concede the fight to end handgun violence in this state.

The FBI knew another possible motive for murder could have been Wales' activities outside the office. He was president of Washington cease fire, a gun control group.

Wales (on tape): I'm talking about simple, reasonable legislation that would hold gun owners responsible for keeping their firearms safely stored and away from kids. All of those have been opposed by the NRA.

His friend Ralph Fascitelli: He went head-to-head with the NRA, you know, probably for a 10-year period. And here was somebody that died - died from gun violence. So it was a pretty cruel irony for everybody involved.

The FBI gave Dateline a rare look inside its investigation. Bob Geeslin is the supervisory special agent assigned to the Wales case.

Bob Geeslin: We took on projects that have never been done, at least from my knowledge, in the Bureau before.

Sara James: Give me an example of a project that's never been done.

Bob Geeslin: The Makarov Project.

Federal prosecutor Tom Wales was a sitting duck as he sent e-mails in the basement office of his Seattle home in October 2001. Investigators believe he never saw the person who shot him through the window: An assassin who remains at large.

Amy Wales feels the loss of her father every day but gets some solace from the memory of the last time she saw her father, shortly before his murder. Amy had just graduated from college, and was about to leave for London.

Amy Wales: He just gave me a really big hug, extended hug. And he said he was very proud of me. And that he loved me. Well, at the time I was like, "Oh, Pa, you know, get over yourself." (laughs) But it has turned out to be one of the most amazing gifts.

To investigators, some of the strongest evidence found at the crime scene was also some of the most baffling.

Douglas Murphy: There was no obvious explanation for it.

Douglas Murphy is a ballistics expert at the FBI lab in Quantico, Virginia. His job is to analyze the bullets and shell casings found at the crime scene. The first task was to identify the type of gun used.

Douglas Murphy: When a firearm manufacturer makes a barrel, they cut grooves in the barrel that force the bullet to rotate. So they have to choose how many grooves they want- in the barrel. There could be four, there could be six, there could be 12.

Although the shell casings found in Wales' backyard said "Makarov" right on them, the number of grooves left on the bullets didn't match a standard Makarov.

Douglas Murphy: Once we discovered this company that made replacement barrels for Makarovs, that's when everything fit.

Sara James: So this then is a replacement barrel.

Turns out, Makarovs can be fitted with an after-market barrel... Sometimes used to improve accuracy. The FBI learned that approximately 2600 of the special barrels had been sold in the U.S.

Bob Geeslin : We have instances now where as we look for these, when we get that chill down our spine that we don't like the answer that we've got.

In one instance, the FBI traced two replacement barrels to Seattle gun dealer Albert Kwan. Kwan was able to account for one barrel and says that's all he ever purchased. The second is still missing, leaving the FBI to wonder whether it might have been used to kill Tom Wales.

Kwan failed a polygraph when questioned about those two gun barrels but is not believed to be the one who shot Wales.

Ballistics and old-fashioned gumshoe work were only getting agents so far. Suspecting there might be more information out there which they'd missed, the FBI created new software to do what's called "data mining" - essentially, digging through mountains of information on incompatible law enforcement computer systems. It's a high-stakes game of connect-the-dots.

Bob Geeslin: Is this ATM withdrawal on this particular day, related to this particular person who owns a particular car?

And in 2004, three years after Tom Wales' murder, agents hit pay dirt - a nugget buried in local police records which hadn't been associated with Wales' murder - that a strange man had been seen very near Wales' home in the two weeks before his slaying.

Bob Geeslin: This person simply did not fit.

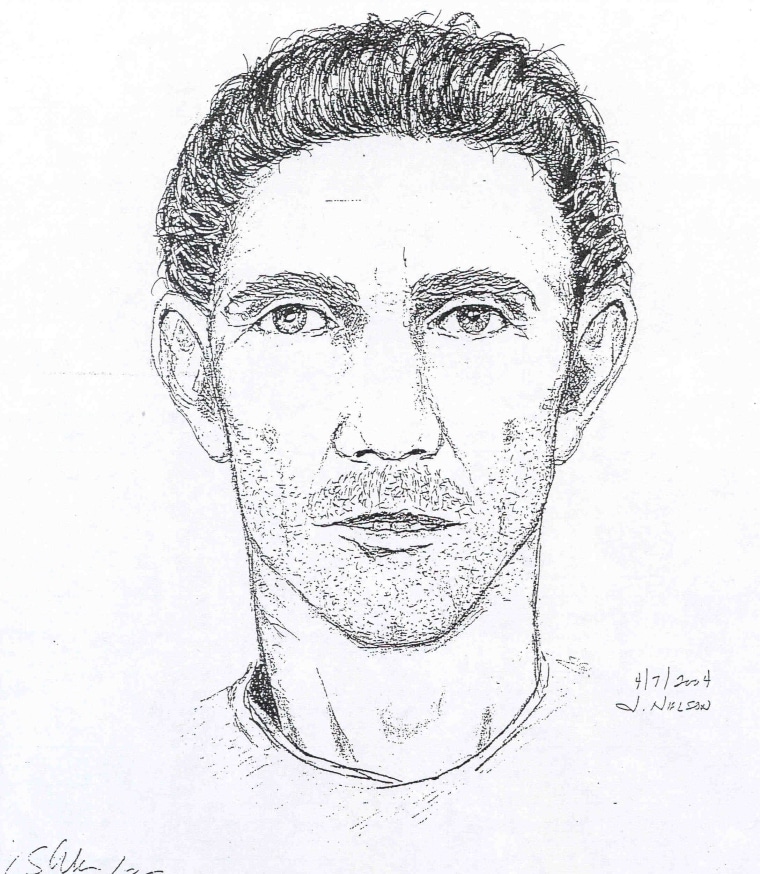

The FBI made a composite drawing based on what neighbors had seen, then appealed to the public for help identifying the unknown man.

Bob Jordan at press conference:

They are described as a white male approximately 5'7"- 5'10" tall.

Witnesses describe the man as weighing 140-165 pounds, his hair pulled back in a ponytail. He had tobacco-stained teeth and a chipped front tooth and was wheeling behind him a small black nylon suitcase.

Sara James: Do you believe that the person carrying or rolling the suitcase behind him was the murderer of Tom Wales?

Bob Geeslin: I have no idea. What we're looking for is just to talk to a person who fits the description to find out what they were doin'. It could have been a - a vacuum cleaner salesman.

Meanwhile, as agents continued to run their fancy computer programs, and follow up countless leads on both coasts, a vital clue suddenly fell into their laps.

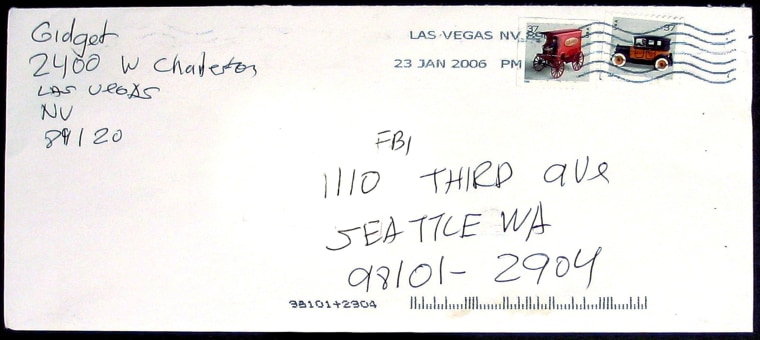

The biggest lead in years came through the mail, a clue sent to the FBI office in Seattle nearly five years after Wales' murder. It was a letter, postmarked Las Vegas. Perhaps most intriguing to investigators was the name in the return address: "Gidget".

Shawn Van Slyke: The author of the letter purported to be the true killer of Tom Wales.

Was it a cruel hoax? Or had the "Gidget letter" really been written by Wales' killer?

Nearly five years had passed since assistant U.S. Attorney Tom Wales was murdered when, out of the blue, a mysterious envelope arrived at the FBI office in Seattle: An anonymous letter from someone who claimed to be Wales' killer.

Shawn van Slyke is a behavioral analyst for the FBI, part of a team of agents specially trained to read between the lines.

Shawn Van Slyke: It's very difficult to suppress those life-long linguistic habits that have developed over a lifetime, based upon a particular offender's exposure to popular media, or his education or what other life experiences he may have encountered.

Agents immediately began picking apart the typed letter noun by verb by adjective. In it, the author describes how he was broke and living in Las Vegas when he received an anonymous call from a woman... A woman looking for a hitman.

letter being read:

So I drove to Seattle to do the job. I did not even know his name. Just got laid off from a job. Nice talking lady. I didn't know her name.

The letter also provided a detailed scenario of the shooting.

letter being read:

I kind of camped out in the backyard of this house and waited for the guy to settle in at his computer. Once he was there, I took careful aim. I shot two, or possibly more times, and watched him collapse. I absurdly waited a few minutes and then left. I was sure he was dead.

Shawn Van Slyke: What would the true motive of this letter be?

While Van Slyke and his team considered the letter to be an extremely valuable clue, they found the story it recounted - a professional hit man taking a job on spec from a stranger - implausible - even ludicrous.

(FBI roundtable discussion)

And you'll never find a hit man who would do the job without any sort of payment up front. You would never find a hit man in my experience who will then, after the job, attempt to communicate with law enforcement via a letter such as this.

And so the team of specialists began looking beyond just what the author said to how he or she said it - from grammar to word choice - looking for any clues that might lead them to the killer.

Shawn Van Slyke: The style is somewhat reminiscent of a day gone by, an era gone by. Somewhat reminiscent of those 1960 cheap detective novels. And with that staccatto rhythm.

And what about that name in the return address-- "Gidget"?

Shawn Van Slyke: It's very likely that this author had some exposure to that term in the past. Whether it be watching the movie or the television series. Or perhaps having a girlfriend or family members that he referred to "Gidget" in years gone by.

While investigators don't buy the story laid out in the letter, they do believe it was sent by someone involved in the crime. The motive? To throw the investigation off track or perhaps to create a false evidence trail to convince a future jury that some unknown suspect, the anonymous author of the Gidget letter, could be the real killer.

Bob Geeslin: Do I think it was a taunt? I think it was a taunt.

The FBI won't say whether it was able to lift fingerprints or DNA evidence from that letter or envelope. But this new piece of evidence would lead agents back to someone they'd looked at before: that pilot who they believed held a grudge after tangling with Wales in court.

Wales had discussed the man with friend Ralph Fascitelli just one week before he was gunned down.

Ralph Fascitelli: The guy was very bright. But he was off-kilter. And he felt he was manipulative and he was very astute, using legal techniques, and he felt he was very vengeful.

In the winter of 2006, the FBI discovered a striking coincidence between the Gidget letter and the pilot. Remember, that letter was post-marked Las Vegas.

Seattle Times reporter Steve Miletich: The pilot had flown to Las Vegas just about the time this letter was postmarked.

As investigators saw it, there were two potential motives. First, could a perception of wrongful prosecution by Wales have led to murder? Remember, the commercial airline pilot had a side business selling crashed and re-built helicopters. The pilot's company was accused of violating FAA rules. And so the case was assigned to Tom Wales and Robert Westinghouse. Westinghouse says the pilot didn't take it well.

Bob Westinghouse: He was simply personally affronted by the entire prosecutive effort.

Sara James: Was it an unfair prosecution?

Bob Westinghouse: Absolutely not.

In the end, the serious charges were dropped and the company pleaded guilty to a misdemeanor. But the pilot claimed he was out $128,000 dollars in legal fees and in an extraordinary move, filed that lawsuit against the U.S. Attorney's office and Tom Wales specifically- claiming malicious prosecution. That case was dismissed after Tom Wales was killed.

Investigators believed a second potential trigger for the pilot could have been televised statements by Wales shortly after 9/11.

Wales on tape on TV:

I think we need to be careful that we don't do things that are going to further endanger American lives. And I'm afraid that this is going to do precisely that.

Remember, Wales was a gun-control advocate. And soon after 9/11, he spoke out publicly against allowing pilots to carry guns in the cockpit. Turns out, the angry pilot who sued Wales was also a gun enthusiast.

Tom Wales: We have to ensure that they have the integrity in the cockpit that they need to do their job and that means air marshals if we need it, it means increased security at the checkpoints and it means some pretty darned secure locks on the cockpit door.

Steve Miletich: That interview ran over and over on a cable station here in town. There's no way to absolutely know, but it's very likely that this pilot saw that interview. And it might have been part of this continuum of events that - that some people believe would be enough to make him angry enough.

But wait -- what about the pilot's alibi for the time of the murder? That call from his home around 10:40 pm, the very time Wales was attacked. Agents are taking a closer look at that, too, wondering whether some sort of call-forwarding technique had been used to make it appear as though the pilot was home when he wasn't.

Steve Miletich: That's clouded in a whole lot of mystery.

The pilot declined Dateline's request for interview. And has also declined to talk to the FBI. And so, the FBI says, nearly seven years and 10,000 leads later, there isn't enough solid evidence for an indictment. Of anyone.

Bob Geeslin: The case can't go cold in the FBI. There's no statute of limitations. It will continue to be open. Is there a point that you would say that we have covered every reasonable lead that we know of to now? Yeah, absolutely.

Sara James: But you're not there?

Bob Geeslin: We're not even close. We're not even close.

While Wales' friends and family support investigators, there has been criticism of how the case has been handled, particularly in the early days of the investigation.

Sara James: Tom Wales was shot one month after 9/11. Were there missteps as a result of the fact that the FBI was having to be in a lot of places and investigating terrorism threats?

Bob Geeslin: There certainly weren't any missteps that I've recognized that has changed the tenor of this case.

But in 2002, U.S. Attorney John McKay in Seattle complained to higher-ups back in Washington, D.C. that not enough resources were dedicated to the case. Later, McKay was among a number of prosecutors fired by then-Attorney General Alberto Gonzales, leaving Washington state officials wondering if his complaints were the reason he was fired.

Regardless, additional agents were later assigned - and Bob Geeslin was brought on board in 2006.

Bob Geeslin: We effectively more than doubled the numbers here in the Seattle and the Portland offices.

The FBI is known for its patience. It took nearly eighteen years to catch the Unabomber and in the end, the case was solved when his brother came forward with suspicions.

Bob Geeslin believes the same could happen in this case.

Bob Geeslin: It may be somebody calling us tomorrow and saying, 'You know what? I have to get something off my chest.'

Nothing would please Wales' Daughter Amy more. She has thought about what it would be like to meet her father's killer… and takes a page from the volumes of life lessons she learned from Tom Wales, the man she remembers as "Pa."

Amy Wales: Sometimes I visualize an unidentifiable person in front of me. And- and I hear myself screaming. And there's this great amount of rage inside of me. But, every single time I think about this, there's a certainty that I would close my mouth and I would walk away.

Sara James: Why?

Amy Wales: I don't know. I think it's because they do not make me, they do not make my life, and they certainly don't define who my father was. I know that ultimately what I really want to do is walk away and live my life and remember my father and he'd be grateful for all that's good.