Besides stockholders whose portfolios were ravaged Monday afternoon, the one person with the most riding on the bailout bill that collapsed in Congress may have been Senator John McCain.

Mr. McCain had announced last week that he was suspending his presidential campaign to work to ensure the legislation’s passage, even at the risk of skipping the first presidential debate unless a deal was locked down. (He later relented, debating without a deal.) He had called for the high-level White House meeting that some participants later called unhelpful. And after some initial hesitation, he had allowed himself to be identified with a bill that he thought necessary even if unpopular.

So when the deal fell apart on the House floor Monday, in no small measure because most of the chamber’s Republicans balked at voting for it, the McCain campaign worked to contain the potential for damage. The first defense was to go on offense.

Douglas Holtz-Eakin, a senior McCain adviser, said “partisan attacks” by Senator Barack Obama and his Democratic allies in Congress had caused some Republicans uncertain about the legislation to turn against it and so had “put at risk the homes, livelihoods and savings of millions of American families.” The Obama campaign immediately dismissed that response as “angry and hyperpartisan.”

'Unnecessary partisanship'

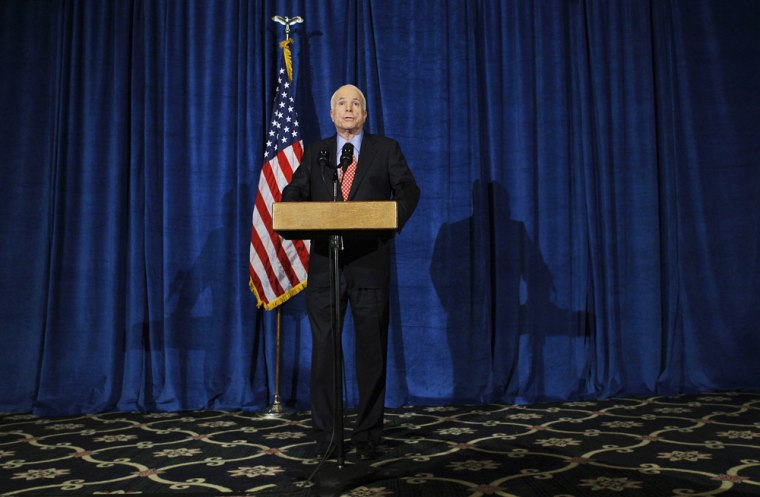

Then, after Mr. Obama had urged Americans and the financial markets to “stay calm” in the wake of the rescue plan’s collapse, while prodding Congress to “get this done,” Mr. McCain hastily called a news conference here in which he, too, seemed to place some blame on Mr. Obama.

“Senator Obama and his allies in Congress infused unnecessary partisanship into the process,” Mr. McCain said, before adding in almost the same breath: “Now is not the time to fix the blame. It’s time to fix the problem.”

Both campaigns pledged to support efforts to resolve the situation, though they were short on details. Mr. McCain’s campaign said he would continue to monitor developments closely to see whether more House Republicans could now be persuaded to vote for the bill, or whether it had to be amended to address their concerns. But his aides said there did not appear to be a need to return to Washington immediately, since Congress had recessed for Rosh Hashana.

Mr. Holtz-Eakin, the campaign’s senior economic adviser, told reporters that “we don’t have a specific proposal that we believe is the magic bullet.”

“Having failed to have that bill passed through the House,” he said, “I think it’s time to regroup and see whether it’s the content, whether it’s the nature of the debate that went on on the floor of the House today, or whether people really just need to take one look around the financial markets and have a wake-up call and do the right thing.”

Mr. Obama had said he was inclined to support the bill that failed Monday. But it remains an open question how much political capital he will seek to expend, or how invested he wants to become, in helping Democratic leaders win passage of a bill.

Surprise in both camps

The failure of the measure took both camps by surprise. Mr. Obama, who was campaigning Monday in Colorado, had already sent reporters the advance text of a speech he planned to give lauding the agreement. And Mr. McCain, at a rally in Columbus, Ohio, seemed to be taking some credit for the bill.

Democrats had said all along that by inserting himself into negotiations, Mr. McCain had brought presidential politics to a delicate situation and could wind up hurting more than helping. After the House vote, his aides bristled at the suggestion that his involvement had in fact been a drawback, saying he had been instrumental in getting House Republicans a seat at the negotiating table and helping bring in more of their votes.

Mr. Holtz-Eakin said Mr. McCain had made “dozens of calls” on the bill, some to House Republicans who opposed it.

Aides to Mr. Obama said he had not directly reached out to try to sway any House Democrats who opposed the measure. But where Mr. McCain had accused Mr. Obama of taking a hands-off approach to the financial crisis, Democratic advisers said they believed that Mr. McCain now had a role in the legislation’s failure.

As aides to both campaigns pointed fingers, Mr. Obama sought to stay above the fray and maintain a steady demeanor that advisers maintain has set him apart throughout the financial turmoil.

“One of the messages that I have to Congress is, Get this done,” he said in Colorado after the House vote. “Democrats, Republicans, step up to the plate and get this done. Understand even as you get it done to stabilize the markets, we have more work to do to make sure that Main Street is getting the same kind of help that Wall Street is getting. We cannot forget who this is for. This is for the American people. This shouldn’t be for a few insiders.”

Michael Cooper reported from West Des Moines, Iowa, and Jeff Zeleny from Westminster, Colo.

This article, With Deal’s Collapse, the McCain Camp Attacks, first appeared in The New York Times.