Is the Electoral College, America’s quirky system of choosing its presidents, on its way to extinction?

Americans do not vote directly for president. They vote for slates of electors in each state.

Collectively, the electors are called the Electoral College. Each state gets a number of electors equal to its membership in the House and Senate. (The District of Columbia gets three.)

Minnesota, for instance, gets 10 electors. If Republican candidate John McCain wins the most votes in Minnesota on Nov. 4, the slate of 10 Minnesota McCain electors is chosen.

All but two states (Maine and Nebraska) use the winner-take-all system. This means that the candidate who gets the most popular votes in a state gets all of its electoral votes.

The next president will be the candidate who gets at least 270 of the total 538 electors.

The system can be idiosyncratic. Four times in the nation’s history, the winner of the largest number of popular votes did not win the largest number of electoral votes, and therefore did not become president.

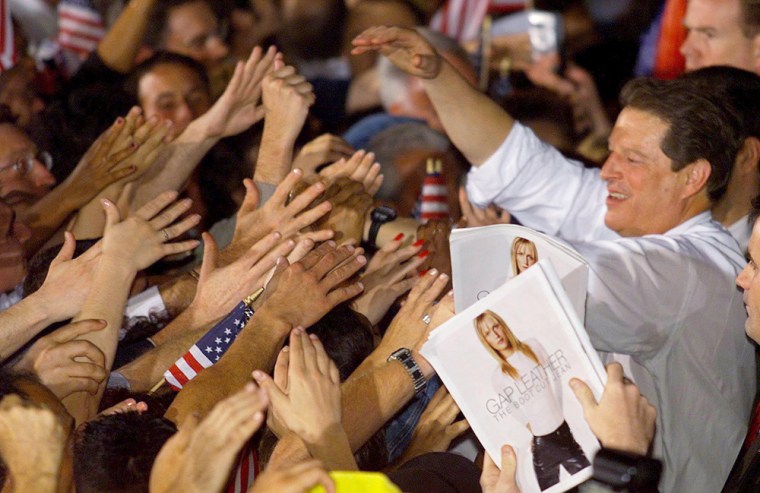

It happened in 2000, when Al Gore got more popular votes, but lost the election to George W. Bush.

It also happened in:

- 1824, when popular vote winner Andrew Jackson lost the presidency to John Quincy Adams.

- 1876, when Samuel Tilden lost to Rutherford B. Hayes.

- And 1888, when Grover Cleveland lost to Benjamin Harrison.

A relic of the early republic

The system is a relic of the early days of the republic when electors were supposed to be independent agents exercising their judgment in choosing a presidential candidate from a list of several contenders.

Today, electors are party loyalists who almost always vote for their party’s nominee.

On Friday, a group of legal scholars, political scientists, and systems specialists gathered at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology for a conference on the Electoral College. Their focus? How to better engineer the system.

Scrapping the electoral vote system would likely require a constitutional amendment since the Constitution itself created the electoral system (Article II, section 1).

But a group called National Popular Vote says it has found another way.

So far, it has persuaded four Democratic-controlled legislatures (in Maryland, Illinois, Hawaii, and New Jersey) to pass a law which commits those states to give their electoral votes to whomever wins the national popular vote.

The accord takes effect once states with a combined 270 electoral votes agree to it.

The states would pledge to award their electoral votes to the popular vote winner even if he or she had not been the majority choice in their state.

Take Maryland as an example. Say 80 percent of voters in that state cast their ballots for the Democratic presidential candidate. But if a Republican candidate wins the national popular vote, under the state law, Maryland's 10 electoral votes would go to that candidate.

Winning the big cities

Abolishing the Electoral College would profoundly change campaign strategy: Democratic candidates could win the national popular vote by concentrating on cities and regions where Democrats are already dominant: Los Angeles, New York, Newark, Philadelphia, Seattle, etc.

Since rural America wouldn’t loom large in this revised strategy, it might hinder Democratic congressional candidates in rural counties and in states like South Dakota and Utah.

But Northwestern University law professor Robert Bennett, who calls himself "a mild proponent" of scrapping the Electoral College and is the author of "Taming the Electoral College," said a popular vote would create incentives for the minority party in each state to improve their organizations and harvest votes.

The Democratic Party in heavily Republican Utah, for instance, would know that every voter it recruited for the Democratic presidential candidate would help win the national election.

Currently, the votes for a Democratic presidential candidate in Utah are, in effect, wasted. No Democrat has ever won the state, or come close to winning it, in 44 years.

Proponents and opponents of scrapping the Electoral College found little to agree on at the MIT gathering.

Judith Best, a political scientist from the State University of New York at Cortland, told her colleagues that the electoral vote system forces candidates to appeal to more than one or two regions, or to one political ideology.

"A president who wins the office by running up huge margins of 80 percent to 20 percent on the Eastern seaboard and the Midwest, and loses by similar margins in the South and the West, is not a president who can govern," she said.

If the United States had used a nationwide popular vote method of choosing the president in 2000, "it would have created 50 Floridas," said Best.

Recounts would have been required in every state. "If we had had direct, non-federal election in 2000, every ballot box in the country could have been re-opened and there could have been court challenges in every state," she said.

"The process would have gone on so long that on Inauguration Day the speaker of the House would have had to have been sworn in as acting president. An acting president would have been a real calamity."

A margin of one-half of one percent

The difference between Al Gore and George W. Bush in 2000 was 540,000 votes out of more than 105 million total votes cast, a victory margin of only one-half of one percent.

With such a slim margin, there’d be every incentive for both the loser and winner to seek recounts so as to get more votes in the states that each one won by a large margin. Another 50,000 votes for Bush in Utah, Georgia and Texas, for example, could have helped him erase the tiny popular vote edge that Gore had.

At the MIT conference, Yale University law professor Akhil Amar dismissed the dire nationwide recount scenario as an exaggerated fear.

Not even the most populous states pick their governors through an Electoral College system, Amar pointed out. If the popular vote is good enough to elect a governor in a state of 8.5 million voters, such as California, then it would work in a national electorate of 120 million voters.

Amar said a direct national election would create healthy incentives for states to compete with each other in getting more of their people to vote — for example by allowing voter registration on Election Day and by mandating that Election Day be a day off, with pay, for all workers.

He even suggested that states might pay people for voting, just as people are paid for jury duty.

But he added, "you do have direct national elections, states will have an incentive to over-compete. One state will say, ‘We’ll let 17-year olds vote,’ and another state will say, ‘We’ll let 16-year olds vote.’ You’ll need to have some federal oversight, which is a good thing, actually."

"Is it really fair if one state lets you to vote for three months, and another only for three hours? These are real issues," Amar said, but "in the end they don’t scare me away."

What would rogue electors do?

While Democrats bitterly recall that in 2000, Gore lost the electoral vote even though he won the popular vote, Bennett said, "There are much more serious problems with the Electoral College than the fact that we might elect a president who didn’t win the nationwide popular vote."

Among the "landmines" Bennett cited: electors who break their pledge to vote for their party’s nominee. Such "faithless electors" could throw the election to the opposing candidate.

A total of 11 electors out of the 21,000 in the nation’s history have voted for someone other than the person to whom they were pledged, but "faithless electors" have never had any effect on the outcome of an election.

If Democratic candidate Barack Obama were to win on Election Day, it might erase the Democrats’ unpleasant memories of 2000 and lessen the momentum for scrapping the Electoral College.

In a best-case scenario for Obama, Democrats would be able to boast that he won 380 electoral votes — a victory the size of Bill Clinton’s in 1996.