In their new book, NBC News political director Chuck Todd and NBC News elections director Sheldon Gawiser provide a state-by-state guide to how Obama achieved his victory, as well as a toolbox for understanding the political implications of the 2008 presidential election. Here is an excerpt:

INTRODUCTION

Once in a Generation?

So how does one sum up the 2008 presidential campaign in just 12,000 words? Who is arrogant enough to think he or she can capture precisely the historical nature of this campaign and election, at a time when the nation seems vulnerable on so many fronts?

It’s possible a historian 50 years from now might be able truly to understand what happened and why the country was ready to break through the color barrier, particularly if said historian looks at the 2008 election through the prism of post–Cold War America.

Since 1992, the country has witnessed nearly two decades of political tumult of a kind it has experienced only once or twice a century. Right now, the country is so enamored with the fact that we’ve broken the political color barrier of the American presidency that we haven’t stepped back and appreciated just what a wild political ride our country has been on.

Since the Cold War ended and America lost its most significant enemy, the Soviet Union, the country has been looking for its political center. Consider the upheaval we’ve experienced as a nation since 1992. First, we had a three-way presidential election in which the third-party candidate was the front-runner for a good part of the campaign. Then, in 1994, we saw the House of Representatives switch control for the first time in 40 years. Next, in 1996, the winning presidential candidate failed to secure 50% of the vote for the second straight election, something that hadn’t happened before in two straight presidential elections in 80 years. Then, in 1998, the nation watched as a tabloid presidential soap opera became a Constitutional crisis, and Congress impeached a president for only the second time in this nation’s history. In 2000, the nation’s civics lesson on the Constitution continued, thanks to the first presidential election in over 100 years in which the winner of the Electoral College failed to win the popular vote, followed by the Supreme Court ruling, which eventually ended the protracted vote count controversy in Florida. In 2001, this nation was the victim of the worst terrorist attack in our history. Then, in 2004, a president won reelection by the smallest margin of any successfully reelected president in modern times. Finally, in 2006, control of Congress flipped after what, historically, was a fairly short stint for the Republicans. All of which brings us to 2008 and what for many Americans is the campaign commonly referred to as “the election of our lifetimes.”

Is this the election that ends a 20-year period of political chaos? The serious problems this country is facing may be the reason that 2008 puts the exclamation point on the country’s post–Cold War search for its political center.

Nine Years in the MakingThe 2008 election got started early, before the first candidate, Tom Vilsack, officially announced in November 2006. The campaign began in 1999, when word first leaked that then first lady Hillary Clinton was seriously contemplating a run for U.S. senator from New York. Her election in 2000 set off the anticipation for what would be a historic first: the potential election of this country’s first woman president.

There was some scuttlebutt that Clinton would run for president in 2004, but ultimately she decided to keep her eye on the 2008 ball. That was when she’d be into her second term as senator and when the field would be cleared of an incumbent president. This country rarely fires presidents after one term. It’s happened just three times in the last 100 years.

The long march of the Hillary Clinton candidacy shaped much of the presidential fields for both parties. The Republicans who announced in 2008 all made their cases within the framework of challenging Hillary. In fact, it was Hillary’s presence on the Democratic side that gave Rudy Giuliani the opportunity to be taken seriously by Republicans as a 2008 presidential candidate. As for the Democrats, consider that many an analyst and media critic like to talk about how wrong so-called conventional wisdom was during the 2008 campaign. But much of it was right. One early piece of such wisdom was that the Democratic primary campaign would be a primary within the primary between all the Democrats not named Clinton to establish an alternative to Hillary.

This sub-Democratic primary, which started in earnest after the 2004 presidential election, looked as if it was going to be a campaign between a lot of white guys and Washington insiders looking for their last chance at the brass ring. Familiar faces like Joe Biden, Chris Dodd, John Edwards, and Bill Richardson must have thought to themselves, If I could only get into a one-on-one with Hillary, I could beat her. Some new names were also seriously considering a run, like Virginia Governor Mark Warner and Iowa Governor Tom Vilsack. None of these potential candidates scared the Clinton camp, because they all were just conventional enough that Hillary’s ability to put together a base of women and African-Americans would be sufficient to achieve the Democratic nomination.

But there was one potential candidate whose name was being talked about by activists and the blogosphere who did have the Clinton crowd nervous: the freshman senator from Illinois, Barack Obama. The factor that kept the Clintons confident about their 2008 chances was the notion that there was just no way, despite his popularity with the Democratic activist base, that a guy who, until 2004, was in the Illinois state senate would somehow have the audacity to run for president so soon. The Clintons were very familiar with the strategy of figuring out the timing of when best to run. They knew 1988 was too soon for Bill, and they took the advice of many and waited until 1992, and they knew that 2004 was too soon for Hillary, and she took the advice of many and waited. Surely, the Clintons must have thought, Obama would follow the same advice.

The most remarkable primary campaign no one seemed to care about

While the Democrats were positioning themselves, the Republicans were in the midst of their own turmoil. This turned out to be a hard-fought primary that few cared about, as the country became obsessed with the most amazing Democratic primary campaign in a generation.

The Republican nomination was seen as completely wide open, mostly because the outgoing incumbent Republican president had not identified an heir apparent. President Bush’s vice president, Dick Cheney, had lost his presidential ambition long ago, and the only other potential Bush heir, his brother Jeb, decided that trying to immediately succeed his brother was probably not the wisest move.

But Republicans love order, or so their presidential nomination contests in the past have indicated. What does order mean for the GOP? If there’s no incumbent president or sitting vice president in the field, then the runner-up from the last contested nominating fight would be deemed the de facto front-runner. In this case it was John McCain since he was the runner-up to George W. Bush in the 2000 primary. Of course, McCain ended up with the nomination, but to this day, it’s a miracle that he was able to win it.

McCain initially portrayed himself as the inevitable nominee, creating a behemoth campaign organization, participating in endorsement buy-offs with his deep-pocketed competitor, Mitt Romney, and trying to enhance his image as a maverick while making nice with various conservatives, including the late Jerry Falwell and evangelist Pat Robertson.

Still, many activists were searching for an alternative to McCain. As a result, McCain struggled mightily to raise money in the first six months of his campaign. His fund-raising was further hampered when he became the highest profile Republican other than George W. Bush to push for comprehensive immigration reform. This legislation, cosponsored by conservative bogeyman Massachusetts Senator Ted Kennedy, fired up the conservative talk radio base and McCain got scorched, drying up his fund-raising and putting him on the brink of having to end his campaign before Labor Day 2007.

But instead of dropping out, McCain essentially filed for Chapter 11 and did a massive reorganization. He drastically reduced his staff to a small band of campaign operatives determined to win the nomination one early primary state at a time. There was one great illustrative moment in the summer of 2007 of this new campaign, postreorganization, when McCain carried his own bags in an airport while traveling alone to a campaign event in New Hampshire.

During McCain’s apparent demise, there was a massive effort by the other Republicans to fill the vacuum. Mitt Romney was vying to be the conservative alternative to McCain early on, which meant he had to tack back on a number of positions he took when he ran for office in liberal Massachusetts. But even with McCain apparently out of the mix, Romney decided not to fill the center but still aimed to become the front-runner by appeasing conservatives. Former New York City Mayor Rudy Giuliani was also in the race but was running on a different plane. He was certainly taken seriously by his opponents because he raised decent money, and his name identification as the mayor of New York on 9/11 meant he led in just about every national poll during the run-up to the Iowa caucuses. But there was always something about his candidacy that seemed like a house of cards. It really wasn’t a matter of if his candidacy would collapse, but when. The collapse began in December 2007, when the New York tabloid press just unloaded, well, everything from Giuliani’s past, from his secretive courtship of his third wife to his relationship with his now disgraced former police chief, Bernard Kerik. Giuliani’s personal problems turned out to be as debilitating as many analysts had predicted. Adding to this politics of self-destruction, Giuliani’s team had crafted a nonsensical campaign strategy that banked on Giuliani skipping Iowa, New Hampshire, South Carolina, and Michigan, while focusing solely on the Florida primary to launch his candidacy. Giuliani joins a long list of presidential wannabes who have attempted and failed to get the nomination by bypassing both Iowa and New Hampshire. While every campaign rule of presidential politics is bound to be broken, this one has yet to be, at least since 1976 when Jimmy Carter used a win in Iowa to catapult himself to the Democratic nomination.

There were two other major players in the Republican contest: on-again, off-again actor and former Senator Fred Thompson and former Baptist preacher and former Arkansas Governor Mike Huckabee.

Thompson’s rise ended on the day he actually announced his candidacy. The idea of a Thompson candidacy began to develop in the conservative blogosphere and Washington salons in the spring of 2007, and when McCain’s campaign nearly collapsed, the idea quickly gathered speed. Essentially, he was one of the best noncandidates in the history of presidential politics. But then he got in the race and his prospects began to deteriorate. The minute he announced, he became ordinary and quickly earned a reputation as being lazy and unenergetic. He just seemed to wing it, hoping the lack of interest in the rest of the GOP field would consolidate support for his candidacy.

If Thompson had a polar opposite when it came to hunger for the nomination, it was Huckabee. Never meeting a TV camera he didn’t like, Huckabee quickly became a media darling of the primary campaign. With each passing Republican debate, it was Huckabee who seemed to be creating immeasurable buzz. While he had little campaign cash, he had a devoted support network, comprised of many social conservatives, including home schooling advocates, who tirelessly put together a very impressive Iowa field organization.

As Thompson was fizzling and Giuliani was campaigning in his own world down in Florida, McCain was hunkering down in New Hampshire, trying to recapture the 2000 magic. The buzz for McCain was not nearly as intense in the fall of 2007 as it was in the fall of 1999, when he came from behind, nearly toppling George W. Bush in the 2000 presidential primaries. But there was something about McCain’s 2008 candidacy that seemed salvageable.

McCain, of course, was helped by the basic fact that none of his other opponents seemed to catch fire. Romney was mired in a fight with Huckabee for the hearts and minds of Iowa conservatives. And Thompson and Giuliani were in free fall. This meant McCain had his opening. The formula was simple: if Huckabee could upset Romney in Iowa, McCain had a good shot to beat Romney in NewHampshire. This would provide McCain a shot of momentum that could carry him through Michigan, South Carolina, and Florida and bring the nomination fight to a close before Super Tuesday.

As it turns out, the nomination fight would end before Super Tuesday, which in 2008 was on February 5. Super Tuesday appeared to be an obvious end date for both primary contests because so many states, more than 20, had decided to move their primary or caucus up to that day.

McCain got what he needed in Iowa as Huckabee upset Romney by a considerable margin, leaving the Massachusetts Republican in poor shape. With New Hampshire coming just five days after Iowa, it was nearly impossible for Romney to turn things around in time. Sure enough, McCain prevailed and got the media spark he was hoping for. In fact, nothing benefited McCain more than his still strong relationship with the national press corps, who seemed eager to write the McCain comeback story out of New Hampshire. When McCain won, the press fell in love with him again for a brief period, just long enough for him to sweep the nomination.

After Iowa and New Hampshire, the only significant speed bump on McCain’s road to victory came in Romney’s onetime home state of Michigan. Romney made a last-ditch effort in the state, eked out a win over McCain, and lived to see another day. But Michigan turned out to be a blessing for McCain. Why? McCain could not have won South Carolina if it were a two-man race against the more socially conservative Huckabee. But with Romney back in the game, Thompson decided to stick around and turned South Carolina into a quasi-four-person race. This was exactly what McCain needed; he won the South Carolina primary without garnering even a third of the vote. Now he had the all-important momentum going into Florida, the last big contest before Super Tuesday.

Romney refused to give up, but he knew it would all come down to Florida. He might have succeeded had it not been for Huckabee. Both McCain and Romney were battling for first, as the third and fourth place contenders—Giuliani and Huckabee—each took support from the top. Giuliani was a drag on McCain, and Huckabee was a drag on Romney. What eventually put McCain over the top was a last minute endorsement by Florida’s popular governor, Charlie Crist. The endorsement was not just in name only. It also meant the governor unofficially mobilized his get-out-thevote machine within the state party. This effort changed what was supposed to be a conservative primary electorate into something more moderate, and proved to be just what McCain needed.

McCain’s was a remarkable comeback story in which he had to make bank shot after bank shot to win the nomination. Florida was the final one on January 29. Romney would continue on through Super Tuesday along with Huckabee. When the votes from the Super Tuesday states were tallied, McCain ended up winning more delegates than either of the two more conservative candidates, leaving Romney defeated and Huckabee ecstatic that he actually mattered. Huckabee had made no secret of his distaste for Romney and spent much of his latter days on the campaign praising McCain, even as he forced the Arizona Republican to run a semicompetitive series of primaries through March officially to get a majority of the delegates. Only then did Huckabee drop out. And that’s when McCain’s general election troubles began.

The Rise of Obama

While the Republican nomination was fascinating, it didn’t hold a candle to what was going on inside the Democratic party. The decision by Obama to run transformed the Democratic primary instantly from a subprimary campaign to determine the anti-Hillary alternative to a two-person clash of the titans. From the moment Obama formalized his candidacy, Clinton’s campaign was transformed into a rapid response operation focused solely on Obama.

When word leaked that Obama was going to form an exploratory committee and would do so on YouTube, Clinton quickly crafted her “I’m in it to win it” announcement, which was also done via the Web.

Interestingly, though, while Obama used new media to announce the formation of his exploratory committee, he went the old school route when formally announcing his actual candidacy—he gave a “Why I’m running for president” announcement speech in front of thousands of supporters in his home state. Clinton never gave a formal “Why I’m running” speech akin to what Obama delivered on February 10, 2007, in front of the Old State Capitol in Springfield, Illinois. This fundamental fact sums up the primary contest about as well as any primary result or delegate count.

Obama outlined the organizing principle for that candidacy via his announcement speech. In fact, the basic themes Obama introduced in that first speech in Springfield would be repeated on the stump throughout the campaign—all the way until his victory speech on Election Night in November 2008.

That initial announcement speech included plenty of phrases which would become familiar to his supporters, such as: “What’s stopped us is the failure of our leadership, the smallness of our politics—the ease with which we’re distracted by the petty and trivial, our chronic avoidance of tough decisions, our preference for scoring cheap political points instead of rolling up our sleeves and building a working consensus to tackle big problems.” In that first speech, Obama also constantly used the refrain, “Let’s be the generation,” as a way to talk directly to new voters; he hinted that his speeches would be a big part of his campaign strategy when he uttered the phrase, “There is power in words.”

While much of Obama’s campaign rationale was evident in his announcement speech, the same cannot be said for either Clinton or McCain. Stunningly, neither gave a “Why I’m running for president” speech. Neither made a formal announcement in his or her home state or any other. Neither outlined in the traditional way a philosophy or program as Obama had done. Clinton made her Web video speech and that was it, nothing else other than “I’m in it to win it.” McCain announced on The Tonight Show with Jay Leno . Just on the basis of announcement strategies, is it any wonder why Obama appeared to be the candidate who constantly was able to stay on message while his two opponents, Clinton in the primary and McCain in the general, were grasping for anything that would stick?

There are several reasons why Obama ultimately won the presidency, but one of the central factors was he always made the case for why he was the candidate of change, the candidate who was change from Bush. Clinton and McCain, when running against Obama, were always caught up in trying to contrast themselves with Obama and highlight his inexperience. Neither offered consistent “change from Bush” arguments. And in a time when President Bush had approval ratings ranging from 25% to 30%, change mattered the most to voters over any other issue.

Of course, Obama didn’t win his nomination by simply holding an impressive kickoff, but he did quickly cement his place as the chief challenger to the then front-runner Clinton. In one fell swoop, Obama was able to displace all of the other anti-Hillary challengers and relegate them to second-tier candidates. John Edwards was the strongest of these second-tier challengers because of his near victory in the 2004 Iowa caucuses. In fact, it was Edwards who started out as the Iowa front-runner simply because of the strength of his organization. But when he didn’t win Iowa, he was toast.

Edwards and the rest of the second-tier Democratic candidates did play important roles in the primary. It was Chris Dodd who may have delivered the knockout blow to Clinton in an October primary debate. He called foul on an answer Clinton gave on whether she supported a New York state proposal to give drivers’ licenses to illegal immigrants. Dodd’s attack on her answer (or nonanswer) started a firestorm and managed to get political reporters worked up over whether Clinton was capable of answering a question directly or whether she was prone to do what her husband was famous for doing and equivocate. Dodd helped the media play up the narrative that a Clinton doesn’t give direct answers.

It was a near-fatal moment for Clinton. While her campaign believes the media pounced unfairly, from that point on, the die was cast, and her lead in the polls began to shrink.

The 2007 preprimary campaign was one of the oddest reality shows in presidential campaign history. It seemed a week didn’t go by without one of the two major parties participating in a debate. These debates turned into must-see TV for many, as the ratings kept going up as Iowa got closer. And as the field of candidates shrank, particularly on the Democratic side, these debates became more important.

But for Obama, 2007 was about getting his sea legs. While his kickoff was near perfect, he struggled in the first five to six months of his candidacy as he tried to build a campaign that was more than just an idea. Resources weren’t a problem as his campaign kept up with Clinton dollar for dollar and, as it turns out, was spending those dollars much more wisely. Obama’s problem in the summer and early fall of 2007 was that he wasn’t breaking through, particularly in the debates.

But debates were never Obama’s strong suit. The key to his campaign were his speeches. At every moment in the primary when he was in need of a lift, it was a formal speech that jump-started his campaign. When questions were building among the chattering class about Obama’s presidential campaign and his inability to catch Clinton in the polls, Obama delivered a stem-winder of a speech at the Iowa Jefferson-Jackson dinner in November 2007, drowning out the other speeches. In hindsight, if there was a moment that Obama truly caught fire in Iowa, it was that night in Des Moines in front of 10,000 Democratic activists.

Of course, the other big speech that bailed Obama out of a tough spot came after the Reverend Jeremiah Wright episode. Wright was Obama’s pastor in Chicago and became a familiar face to many Americans; in March 2008, excerpts of some of Wright’s more controversial sermons were aired almost nonstop on cable news channels. There was hateful, and to some, un-American rhetoric being spewed by Wright, who was described as the man who helped Obama find God and the man who married him and baptized his children. This was not some made-up close relationship pushed by Obama’s opponents, as with 1960s radical Bill Ayers.

Obama had treaded carefully on the race issue for much of the campaign, doing what he could to be “postracial.” It’s not as if he ran away from his ethnicity; it’s that he didn’t dwell on it. But he didn’t have to; everyone else did in every profile of him written early in his political career. Of course, his unique background, being an African-American with no U.S. black roots, meant many white voters viewed him through a different prism than they had other black presidential candidates, most notably, Jesse Jackson.

But the Wright episode had the potential to upend Obama’s candidacy and the candidate knew it, hence the decision to give a major speech about race. His March 2008 race speech in Philadelphia was very well received, as he did his best to send the message that he viewed the race issue through the eyes of both black and white America. It seemed to put a period on the Wright affair, and most important got the cable news channels to stop running the Wright sermons on a continuous loop. Wright would resurface just before the May primaries in Indiana and North Carolina. His bizarre appearance before the National Press Club was so antagonistic that Obama decided to quit Wright’s church and publicly rebuke him. It appears that whatever close relationship the two did have at one time no longer existed. Wright wouldn’t pop up again during the campaign, and he really wasn’t used in any negative TV ads against Obama. John McCain pledged early on that he wouldn’t do it and he kept his promise, to the chagrin of some Republican strategists.

The Empire Strikes Back?

Of course, after Obama won Iowa, thanks to the launching pad of his November Jefferson-Jackson speech, it seemed as if he was going to do what John Kerry did in 2004, roll up primary and caucus victories quickly, and win the Democratic nominating fight before it even got to Super Tuesday.

But something happened in the five days between Obama’s stunning Iowa victory and the New Hampshire primary. Hillary Clinton became more human, at least for a day. As pundit after pundit and poll after poll were in the midst of declaring Clinton’s candidacy DOA (even the Clinton campaign thought it was over; a bunch of staffers were preparing to be fired), Clinton got a tad emotional at one famous event less than 24 hours before the polls opened in the Granite State. It was the tears felt round the world; whether she actually cried or just got choked up, the important thing was Hillary showed a pulse and New Hampshire voters, particularly women, were smitten. She came back to win New Hampshire and eke out a victory in the Nevada caucuses, putting the pressure back on Obama to do well in South Carolina at the end of January.

It was at this point in the campaign that the Democratic electorate started to break into two very formidable coalitions. The Obama coalition was made up of African-Americans, collegeeducated whites, and young voters. Clinton’s coalition was Latinos, women, and non-college-educated whites. Depending on the state, these coalitions were fairly matched and the national polls showed it. But Obama’s coalition proved to be the winning one for a few reasons, mostly a matter of timing. The primaries in February featured states that were dominated by Obama’s coalition, while Clinton’s coalition really didn’t dominate any state primaries until much later when the campaign was all but over. Had the Kentucky, West Virginia, and Pennsylvania contests been held in February, and Virginia, Wisconsin, and Mississippi in May, there may have been another nominee.

After Clinton’s win in Nevada, her campaign was cocky enough to believe it could be competitive in South Carolina. Why? Bill Clinton’s supposed popularity with African-Americans was thought to be strong enough to secure Hillary at least a quarter of the black vote. Winning 25% of blacks in the Palmetto State wouldn’t be enough to stop Obama from winning in South Carolina, but it would be enough to keep him from blowing the doors off the Clinton campaign. But the more Bill campaigned, the more he kept tripping up on the racial front. He seemed publicly to be too dismissive of Obama for many black voters. In effect, Bubba was seen as dissing Obama, and this caused the black vote to solidify for Obama in a way that even the Obama campaign didn’t expect.

During the summer of 2007, Clinton would regularly outpoll Obama among black voters, particularly older black voters. But the more Bill Clinton ramped up in his critiques of Obama, the more black voters started moving toward Obama. It also helped that black voters viewed Obama as electable. Besides Bill Clinton, the other important moment for Obama in his capability to solidify the black vote was winning Iowa. When African-Americans saw Obama win that very white state of Iowa, it sent the message that maybe their vote wouldn’t be wasted on the young rising star of the Democratic Party.

Obama won South Carolina by a landslide, setting the stage for Super Tuesday, though with one hiccup. A few days after South Carolina, Florida was holding what the Democratic National Committee (DNC) called an unsanctioned primary; Michigan held a similar one in mid-January of 2008, but Obama successfully pulled his name off the ballot there. Clinton won Florida big since Obama never campaigned there. But the key to Obama’s success in states where he campaigned was TV advertising. So in both Florida and Michigan where Obama didn’t buy TV ads, he was a distant second choice behind Clinton. These primary victories would later serve as a rallying point for Clinton supporters—particularly when they made the argument about which candidate was winning the national primary vote—during their desperate attempt to catch up to Obama in the delegate count. The party would eventually resolve this dispute by halving the delegation in Florida and splitting up Michigan nearly evenly, making Clinton’s victories as hollow in the delegate count as they were when the primaries were actually held.

Subtracting Florida and Michigan, Clinton and Obama were even in the number of contests won going into Super Tuesday at two apiece. But while the two candidates looked even on paper, it was a misnomer, as this was the point where the Clinton campaign would lose the nomination. The Clinton campaign had a money problem, a big one, so they had to pick and choose their spots on Super Tuesday, a day when more than 20 states were holding primaries and caucuses. This was not an issue for Obama. Low on resources, Clinton decided not to spend a lot of money organizing in the caucus states on Super Tuesday. Instead the campaign concentrated on the big delegate prizes of New York, California, New Jersey, and Arizona, among others. In many ways, Clinton’s strategy was successful. In just about every state in which she spent serious time organizing and campaigning, she won. But Obama organized and campaigned in every state, even ones he lost. He dominated the primaries in the South, but he also won in the Midwest and Northeast, but more important, he swept all of the caucus states, including Colorado and Minnesota, and also smaller states like Idaho. So, while Clinton won the more glamorous big states, Obama was racking up Democratic delegates everywhere, including in those so-called big states he lost.

As close followers of the Democratic nominating fight will remember, the Democratic Party awards delegates to any candidate earning at least 15% of the vote in any congressional district of any state. So even if Clinton won California by some 20 points, Obama was still picking up sizable chunks of delegates. But Clinton was getting trounced in the caucus states, so badly that she came close to getting shut out in a few states. The most glaring example of this Clinton miscalculation was the delegates earned by Obama in Idaho versus the number earned by Clinton in New Jersey. Obama won Idaho and netted 15 more delegates than Clinton. She won New Jersey, not by an insignificant margin, but netted fewer delegates than Obama’s gain in Idaho. It was miscalculations like this one that cost the Clinton campaign dearly.

The Obama delegate operation ran circles around the Clinton campaign and by the time all of the delegates were counted after Super Tuesday, it was Obama, not Clinton, who won more delegates that day. (He also won more states and was about even in total votes so there really wasn’t a barometer for the Clintons to prove they were ahead.) Clinton may have won the bigger states, but Obama was garnering the votes that mattered. When Super Tuesday came and went, the Clinton campaign was broke and behind. The Obama campaign was just getting started. A week later, Obama would sweep the Potomac primaries, Maryland, Virginia, and D.C., and go on to win 11 straight contests, forcing Clinton to make a final stand on Junior Tuesday, the March 4 primaries in Ohio and Texas.

But while the news media was soaking up the Clinton theatrics about the Ohio-Texas do-or-die, a very important event had already occurred: Obama had built a delegate lead that was close to insurmountable, thanks to the proportional system of delegates. His 100-plus delegate lead from his February sweep through post-Super Tuesday states may have looked close in the raw total, but it wasn’t.

While Clinton did well on Junior Tuesday by winning Ohio and Texas, she netted less than a dozen delegates for her efforts. The die was cast and all Obama had to do was run out the clock. But all was not smooth going: there was the aforementioned Reverend Wright episode in the run-up to the Pennsylvania primary. And Obama’s loss in the Pennsylvania primary raised concerns among some Democrats that he couldn’t win the working-class white vote in the general election and gave Clinton even more life, or so it seemed. Then Obama won North Carolina by double digits and nearly upset Clinton in white working-class-heavy Indiana on May 6, leading smart observers to publicly acknowledge that the race was over. In fact, on that famous May night, the late Tim Russert said first what every smart politico knew, “We now know who the Democratic nominee is going to be.” And that nominee was Barack Obama.

It was a primary campaign for the ages; one that probably lasted longer than it should have because of the media’s fascination with the Clintons. But it was still something else. Every Tuesday night, more and more folks kept tuning in to see what would happen next in America’s favorite reality show. Could Obama win working-class white voters? Would college-educated white women start breaking more for Clinton? Would Hillary finally drop out? What would Bill Clinton say next?

To think that we’re writing a book on how Obama won and mostly talking about the general election is to dismiss a very important, if not more important, part of Obama’s rise and maturation as a presidential candidate. The long, drawn-out primary campaign with Clinton did more to help Obama than hurt him. He became a better debater, not a great debater, but a better one. He became a candidate who could speak a bit more from the heart than the head on economic issues. And of course, without Clinton, he never would have had to run campaigns in all 50 states (and Guam and the Virgin Islands and Puerto Rico...). If Obama never had to run a 50 state campaign in the primaries, would he have been able to put Indiana in play in the general election? What about North Carolina? And would Virginia have turned blue so easily without Obama’s early primary efforts?

Many an Obama operative seethed at the selfishness of the Clinton campaign during those draining primary moments in March, April, and May, because they knew she couldn’t win and she had to know that as well. But Clinton staying in this race as long as she did only helped Obama. And Obama, the candidate-turned-president, knows it. It’s why the highest-ranking cabinet slot went to her.

McCain's Wasted Opportunities

The most interested spectator for the greatest reality show on earth in the spring of 2008 was John McCain. While Obama had to trudge through 48 states (not including Florida and Michigan) and Puerto Rico to fend off Clinton, McCain was able to wrap up his nomination by campaigning in all of four states. Being the nominee on the sidelines should have been an enormous advantage. This should have been the time for McCain to ratchet up his national organization, hone his general election message, begin the VP vetting process, and raise the boatload of money he would need to keep up with the financial juggernaut that was and still is Barack Obama.

As it turns out, McCain apparently did very little of those things. Many a McCain apologist argues that his candidacy was doomed by outside events, like the economic meltdown in the fall of 2008 or the fact that President George W. Bush had the lowest ratings of any two-term president since the archiving of polling numbers began. But while Bush and the economy were enormously heavy anchors on McCain, it does not excuse the wasted three month head start he had on Obama.

Summer Slumber

Sensing the country needed a breather from the primary, both McCain and Obama sparred at a low level for much of the summer. There was the McCain challenge to Obama to keep his word on taking public financing, rather than paying for his general election with private donations. Also, McCain attempted to push Obama into holding a series of 10 joint town hall meetings, an idea that many in Obama’s orbit liked but the top leadership did not. The thinking by some Obama aides was that the more Obama debated or appeared with McCain, the more presidential he would look because he’d be soaking up the gravitas McCain exuded. But the chief deciders in Obamaland believed the McCain town hall gambit was designed to keep Obama tied down, and they didn’t want to be spending days prepping for town halls, instead of putting new states in play by visiting Montana, Indiana, or North Carolina. If the Obama campaign was going to play in 20 or more states, they needed as much summer travel flexibility as they could find. Ultimately, the Obama camp agreed to do a few town halls but the McCain stand was “10 or nothing” and nothing happened.

As for the campaign finance challenge, McCain made it because 1) he was the father of campaign finance reform via the McCain- Feingold legislation and 2) he couldn’t raise the money Obama could raise privately so the only way he could level the financial playing field was to make an issue of Obama’s keeping the public financing pledge he had made during the primary campaign. But the Obama folks backed out of the deal because they knew how much money they’d be leaving on the table. They also knew the public didn’t care about campaign financing as long as money was being raised legally. It may be hard for campaign finance reform advocates to read this, but the evidence is clear.

Obama and the Democratic Party raised approximately $1 billion for this campaign; McCain’s haul wasn’t shabby as the combined total of his campaign and the Republican Party stash was over half a billion dollars, but that nearly two to one advantage in spending is why Obama could afford to experiment with putting new states in play like Indiana, North Carolina, and Georgia, while McCain had to take risks like holding off on buying Florida TV time and calling Obama’s bluff in Indiana, Georgia, and Montana.

European VacationThe general election really didn’t take off until Obama set out on his weeklong international tour of world hotspots and European capitals. The culmination of the trip was a speech in Berlin in front of some 200,000 spectators, a scene that seemed to leave much of this country awestruck by Obama’s worldwide popularity.

With their backs against the wall, the McCain campaign was desperate to bring Obama back down to earth. They launched perhaps the most famous TV ad of the 2008 campaign, calling Obama the “biggest celebrity in the world” and comparing him to Paris Hilton and Britney Spears. Needless to say, this ad served as cable news catnip and got tons of attention. The McCain strategy was clear; they intended to make Obama’s popularity a liability. The McCain campaign was attempting to win the experience argument against Obama by invoking celebrity lightweights like Paris Hilton.

The tactic worked. Obama didn’t get the big bump from his very well orchestrated international trip. If anything, Obama’s narrow three to six point lead throughout the summer started to shrink a bit, as the race fell within the margin of error in the polls. The more important aspect about this moment in the campaign is that it really did signal the start of the general election. And everything from this point on in the race was a blur.

The McCain folks were proud of their ability to deflate the bounce they expected Obama to receive from his overseas adventure. But the campaign leadership may have learned the wrong lesson from this moment: that tactics were the secret to keeping McCain viable. The campaign would never have as effective a hit on Obama after the Paris Hilton ad but would spend a lot of energy trying. Whether it was the pick of Sarah Palin as running mate, the decision to suspend the campaign, or the introduction of “Joe the Plumber,” the McCain campaign used a series of tactics with no overall strategy.

As we’ve mentioned before, it is telling that McCain never gave a formal announcement speech for president. If he had no organizing principle from the beginning, how was he expected to find it as the campaign wore on? Our NBC colleague, Tom Brokaw, liked to compare the McCain campaign team to guerilla war fighters. They could do quick strikes and shock their foes for a day or two, but like many unsuccessful guerilla armies, the McCain campaign could never advance on the general election battlefield. They never took new ground, never forced the Obama campaign into retreat. The best the McCain campaign could ever do was slow the Obama campaign from advancing; they never stopped them.

VPMatch.com Selects Biden

If there was one month the Obama campaign would like to forget, it’s August. Obama’s chief strategist, David Axelrod, said as much in many of the campaign postmortems. It all started with Paris Hilton. The Obama campaign was caught flat-footed; they really thought this overseas trip would help Obama on the question of “Is he ready?” but the Paris Hilton attack blunted any benefit. The campaign muddled through the month, focused on their vice presidential selection process and orchestrating their convention. There were two potential pitfalls at the convention: figuring out a role for the Clintons and living up to the hype on Obama’s own acceptance speech, since the decision was made to move the convention’s final night to an 80,000 seat football stadium. The Clintons’ convention speeches were very well received and seemed truly to bury the primary hatchet. As for Obama’s convention speech, it’s hard to evaluate it since a certain Republican vice presidential candidate completely sucked the air out of it a mere 12 hours later.

Obama’s vice presidential selection process was fairly predictable. This is another case in which the campaign and the conventional wisdom crowd were in sync. Despite all of the cable chatter by uninformed hype-analysts about putting Hillary Clinton on the ticket, the campaign believed Obama needed someone safe, and safe meant an older white guy with impeccable foreign policy credentials. Obama, himself, wanted to be a bit more daring. He was personally impressed with two of his early primary supporters, Kansas Governor Kathleen Sebelius and Virginia Governor Tim Kaine. But the political reality was that he couldn’t pick a woman running mate not named Clinton, and he couldn’t pick a running mate who had been in his current position for less time than Obama’s own tenure as senator. So the campaign quickly zeroed in on Delaware Senator Joe Biden, one of Obama’s primary opponents.

The Biden pick checked all of the conventional wisdom boxes, including experience, working-class roots (the Scranton, Pennsylvania–raised Democrat was one of the poorest members of the Senate, one of just a handful who were not millionaires), and he’d been publicly vetted a more than 30 year Senate career. This is not to say

that Biden didn’t have a little excess baggage from his unsuccessful bids for the presidency, but nothing disqualifying. Much of the baggage that knocked Biden out of the presidential race in 1988 seemed to have faded away, particularly since he comported himself well during the 2008 primary campaign. More often than not, Biden was judged as one of the better debate performers during the neverending primary debate series.

But because the Biden rollout was conventional, it did little on the polling front, as Obama got virtually no bounce. But he wasn’t hurt either. Much of Obama’s goal for the final months of the general election campaign was making voters who didn’t like Bush and wanted change feel comfortable with him. Biden did that. As the candidate himself would say, Obama is the change, and voters knew that visually. It meant, though, that he needed to surround himself with folks who were reassuring. The Biden pick would foreshadow many of Obama’s initial cabinet appointments as the folks he picked were the conventional, experienced choices, not risky change agents.

The Greatest Sideshow on Earth: Sarah Palin

McCain’s search for a running mate was much less chronicled in the media because the campaign seemed to do a pretty good job keeping their short list close to the vest. One thing they were counting on though, was Obama not picking Biden. It was the one pick the leadership of the McCain campaign thought would be the safest and smartest choice for Obama, the pick that would create the least amount of drama. As one McCain senior adviser put it, “Obama doesn’t have the guts to pick Biden.” What did he mean by that? Biden’s too logical of a choice and too qualified for the job; Obama doesn’t believe he needs that, so pontificated this senior McCain strategist.

But that’s just the thing: the McCain folks constantly misjudged Obama. They believed the stereotype they were trying to create, that he was this out-of-control, egomaniacal, power-hungry politician. It’s one thing to attempt to create that image; it’s another to believe it when you are in charge of setting the campaign’s strategy. McCain’s presumed short list was Joe Lieberman, the sometime Democratic senator who was supporting McCain; Tim Pawlenty, the blue-collar-rooted conservative governor of Minnesota; and Mitt Romney, McCain’s chief primary rival, who was thought to be helpful in the swing states of Michigan and New Hampshire.

The only pick among those three who got McCain’s juices flow

ing was Lieberman. He loved the idea of sending the maverick message again while also trying to steal a bit of Obama’s postpartisan thunder. What better way to show off anti-Bush credentials than picking a running mate who essentially ran against Bush, not once, but twice? (Lieberman ran once against Bush as the Democratic VP in 2000 and again as a failed Democratic presidential candidate in 2004.) However, the senior leadership of the campaign talked McCain out of this pick because they believed it would cause a floor fight at the Republican convention, due mostly to Lieberman’s prochoice position on abortion. The campaign believed it could not control its delegates on the floor and prevent them from nominating an alternative running mate, say, Mike Huckabee. Did McCain really want to cause intraparty turmoil this late in the campaign? (Actually, in hindsight, yes.)

But just because McCain couldn’t pick Lieberman didn’t mean he didn’t want to make a splash. So he went back to the drawing board and asked about a candidate whom two of McCain’s close aides, Steve Schmidt and Rick Davis, had been pushing for for some time: Alaska Governor Sarah Palin. After a fairly brief meeting, McCain gave the nod.

The Palin pick was announced approximately 12 hours after Obama finished giving what the Democratic campaign believed was a historically significant acceptance speech, in front of 80,000 Democrats. The speech was so effective that 13 hours later, barely a word was being replayed. Why? The entire political world was focused on one person, Sarah Palin.

That she took the country by storm is an understatement. The irony, of course, is that she instantly became a celebrity of the level the McCain campaign hadn’t seen since, well, Obama in Europe. There were so many things to learn about her: her husband was half-Eskimo; she had five children, one of whom was less than a year old; her oldest daughter was pregnant; she was a dead-ringer for Saturday Night Live veteran Tina Fey; and she was a self-described “hockey mom.”

Notice what wasn’t on that list: she was a successful governor who had done X, Y, and Z. Or, she was an expert in subject matter X. The pop culture story of Sarah Palin and the image of a working mother was a great narrative. But after that, a perception quickly developed that there wasn’t a lot of “there” there. Of course, she became fodder for the media, was even ridiculed, and that only got the Republican base fired up. To the GOP base, she was a breath of fresh air; the Republican the Republican Party had been waiting to rally around for two years. While the base had never been enamored with McCain, they were taken with Palin. Here was a woman who was practicing what many in the social conservative movement were preaching, whether it was choosing to have a Down syndrome child or pushing her unmarried daughter to keep her baby and get married.

But it would be Palin’s lack of experience that would eventually prove her undoing. Was she the reason McCain lost? No. Did she, in fact, help McCain in certain states like North Carolina and Georgia? Absolutely. But the campaign did her no favors when she was rolled out more as a pop icon and less as someone ready to be president, particularly when voters consistently told pollsters that McCain’s age was a bigger factor than Obama’s race. One of the issues McCain said she was an expert on was energy. But did the campaign ever allow Palin to hold an event in front of an oil rig or a nuclear power plant or a wind farm? The campaign did nothing to reinforce the energy issue in Palin’s background other than to insinuate that any elected official from Alaska is by definition an energy expert because of energy’s importance to the state’s economy.

Palin proved to be an excellent political performer in controlled settings but stumbled in some TV interviews, most famously with Katie Couric of CBS. The experience seemed to scar Palin a bit as she became harder to deal with for rest of the campaign. This was always going to be a tougher political marriage than the McCain campaign team understood. Palin’s political experiences were limited. Sure, she had run for quite a few offices and mostly won, but her staff was limited and her chief strategist was her husband. When she parachuted onto the national stage, she suddenly found herself with political handlers. And when those handlers, in her mind, failed her during the early rollout, she rebelled and refused to take any advice from anyone, relying instead on her gut instincts and her husband.

What the future holds for Palin is unclear. At the start of 2009, she was the most popular Republican in the country with a certain segment of the party. And for candidates running for office in 2009 and 2010, she’ll be the biggest draw for fund-raisers and events. But in order truly to have a national impact on her party and be a player in 2012, she’s going to need to improve her issue credentials. Cult of personality can only get a candidate so far; a proven ability to get things done or pushing a set of substantial issues is necessary to be taken seriously.

As for the verdict of voters, it’s clear, according to the 2008 National Exit Poll, Palin was polarizing. Four out of ten voters said Palin’s selection was an important factor in their vote, but those voters split their votes about evenly between the Republican and Democratic tickets. Fully two-thirds of voters believed Joe Biden was ready to serve as president if required, but 60% of voters nationwide held the opposite view of Palin, saying she was not qualified.

Palin energized social conservatives behind McCain. There was greater consensus on the qualifications of the two vice presidential candidates. For example, 74% of Republicans, 66% of conservatives, and 62% of white Evangelicals thought Palin was qualified to be president. She may have helped shore up the Republican base, but she made it far more difficult for McCain to broaden his appeal. Outside of core Republican groups, Palin’s standing was weak. Sixty-four percent of Independents believed her to be unqualified, as did college graduates. Even voters who say they favored Hillary Clinton over Obama as the Democratic nominee, a group some Republicans expected to defect to McCain because of his inclusion of a woman on the ticket, were not enthusiastic about Palin’s qualifications. Only 12% of Clinton supporters thought Palin had the necessary background to become president.

Election Day Comes Early: The September 15 Economic Crash

The Palin pick did prove to be a short-term spark in early September 2008, as McCain took the lead in many of the national polls for the first time all year. But that lead wouldn’t last for long, as the Palin bounce was nothing more than a bubble just waiting to be popped. And it was. On September 15, Lehman Brothers, one of the financial world’s biggest institutions, failed, leading to a panicky feeling in the country that the worst was yet to come for the economy. It was just after the Lehman announcement that McCain voiced a phrase on the campaign trail, which he will regret for the rest of his life. As the country was watching its economy collapse, McCain claimed that the “fundamentals of our economy are strong.” Within an hour of uttering the phrase at a rally in Florida, a claim McCain had made nearly two dozen times before this dark day, Obama was on the trail mocking McCain’s statement and implying the Republican, like Bush, was deeply out of touch on the economy.

McCain, to his credit, tried to fix the error, but the seeds were sewn; he had lost the economic issue and with it, any remote chance he may have had at the presidency. From this point on, Obama’s numbers would only go up, slowly building a five to ten point lead in the national polls and substantial leads in states like Pennsylvania and Michigan, two blue states McCain was hoping to pick off. In addition, the economic turn for the worse hit four red states particularly hard and created an electoral map that was unnavigable for McCain. Florida, North Carolina, Indiana, and Ohio were all red states that were especially hit hard by the economic downturn.

McCain would try various gambits to attempt to get back in control of his fortunes, from suspending his campaign to work out the deal to get a financial bailout package passed in Congress to introducing the country to a working-class hero named “Joe the Plumber.” None worked, and if anything the public saw through the efforts as nothing but political stunts.

After the Lehman collapse, much of the presidential campaign, believe it or not, seemed to play second fiddle to the events of the moment. Bush’s treasury secretary, Hank Paulson, was as familiar a face on the tube as either McCain or Obama in the final weeks of the campaign.

The debates, not surprisingly, were dominated by the economic crisis, even those debates that were supposed to be about national security. But the debates provided McCain no breakthrough moments, as it seemed every debate was held on a day when the nation was gripped with economic anxiety. On the day of two of the three presidential debates, the stock market dropped 500 points, making a bigger impact on the average voter than anything the candidates said in their 90 minute exchanges.

Obama won the debate season, according to the polls, and from then on, things were smooth sailing. The only unknown, at least as far as many observers were concerned, was the role of race. Would there be a “Bradley effect”? Would McCain overtly play the race card at the end in order to test the notion?

Well, neither occurred. The Bradley effect was never proven to be real. The theory is that white voters lie to pollsters about their support for a black candidate, only to enter the voting booth and

pull the lever for a white candidate. What seemed true in the past for some major black candidates is that some white voters would say they were undecided if they feared seeming racist to a pollster, but they wouldn’t lie about supporting the candidate. The correct term for this is the “Wilder effect.” Doug Wilder was the first black governor elected by a Southern state (Virginia) since Reconstruction. He had a big lead in the polls going into Election Day 1989; one trusted poll had Wilder up 50% to 41% with the rest undecided. Well, just about all of the undecided went to Wilder’s opponent and Wilder squeaked out a victory, barely garnering over 50%.

It was this Wilder effect the McCain camp was hanging its hat on. And, in fact, there was some evidence that there was a mini- Wilder effect in the Democratic primaries. Clinton regularly was judged as the better “closer” and would always do better among the “late deciders” than she did overall. Obama would never lose support from the preelection primary polling; his levels just wouldn’t grow at the rate Clinton’s support levels would grow.

But as we learned on Election Day itself, there was no Wilder effect; late deciders split evenly and Obama’s seven to nine point lead and his lead in most of the battleground states held up. If race was a major factor for some voters, it was for a very limited set of voters.

To McCain’s credit, he never played the race card. Did some of his supporters? Yes, but McCain’s campaign never did it; it was not the way McCain wanted to win as he knew it would mean he’d have a compromised presidency. McCain’s senior leadership, in fact, feared that they might somehow win a narrow Electoral College majority while losing the popular vote and race would be the reason why.

The Election Is as It Was Supposed to BeIn many ways, the actual results of the presidential race were as expected; they were quite unremarkable if one understood how the fundamentals of the political landscape so favored the Democrats throughout all of 2008. Obama’s victory margin was what it should have been for a generic Democrat against a generic Republican. Yes, it was a long, strange trip to this eventual normalcy that the electorate delivered, but it was what it should have been.

Republicans were trying to win a third term in a year in which the economy was extremely weak and the Republican Party brand was as poor as it had been since the Great Depression. As many a McCain apologist would utter postelection, it’s remarkable they were in the race as long as they were.

Lessons for the Future

Before we delve into the numbers of how Obama won and debate whether 2008 is another year like 1980, in which the country experiences a long-term political realignment, it’s worth discussing a few lessons from the 2008 campaign for candidates in 2012 and beyond.

- Campaigns matter: Obama proved that the old Woody Allen adage is still true, “Eighty percent of success is showing up.” Obama showed up in more battleground states than any presidential candidate in 20 years, spending resources in places Democrats hadn’t seriously contested in decades. And the gamble paid off. Sure, Obama was assisted by an awful economy that made voters in places like Indiana and North Carolina more susceptible to his change message than they would normally be, but he never would have known whether he could compete if he hadn’t shown up.

Debating Realignment: We Don't Yet Know but...

There are plenty of ways to slice this election and proclaim that X is what won Obama the election. X could equal Bush or the economy or African-Americans or new voters or money or the suburbs or, well, you get the picture.

But let’s start with the simple question on the minds of many political observers; was the 2008 election the start of a political realignment in favor of the Democrats?

The answer is: we don’t yet know. Political realignments aren’t known until a few years after they happen. Frankly, it wasn’t crystal clear that 1980 was a political realignment until as early as 1988 and maybe as late as 1994.

But here’s what we do know: there is an opportunity for Democrats to make 2008 a realignment election; they simply have to govern smartly and popularly. If they do that, they could see themselves in power with a 52% to 55% coalition of supporters for a decade or more.

INSIDE THE AMERICAN ELECTION 2008

Demographically Speaking, Times are Tough for GOP

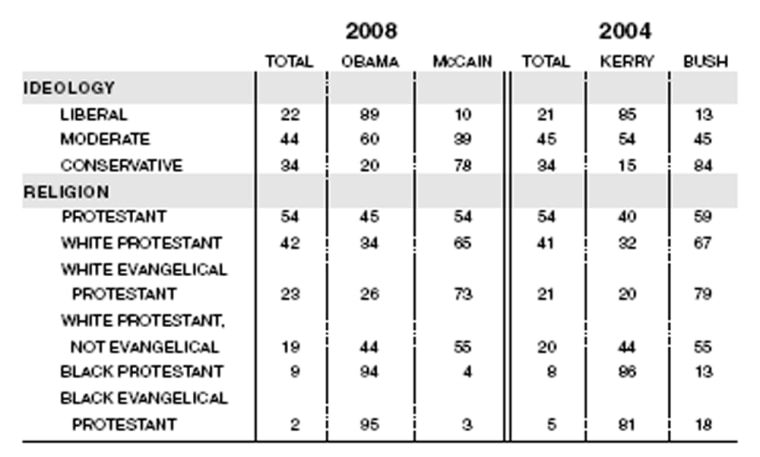

Obama’s victorious coalition in 2008 was impressive but not radical. The portrait of the electorate in 2008 was roughly the same as it was in 2004, with a couple slight, but important differences.

While the coalition of voters that supported Obama reflected the increasing diversity of America, and while Obama made gains across almost all demographic subgroups, the majority of his support came from white voters. Sixty-one percent of his supporters were white, 23% were African-Americans, and 11% were Hispanic. In contrast, 90% of John McCain’s supporters were white.

There were fewer white voters to win or lose. This is a huge

potential problem for the GOP especially if you consider that in 1976, only one in ten voters was not white, 10%. In 2008, one in four voters was not white, 26%, and guess what, the white vote isn’t enough to power the GOP.

Obama did as well among white voters as any previous Democratic presidential candidate since Jimmy Carter in 1976, when 47% of whites cast their votes for the Democrat. In 2008, 43% of white voters nationwide voted for Obama, while McCain won 55% of the white vote.

Apart from whites under 30, McCain won a majority of every other age group of white voters. This appeared to limit Obama in many traditionally Republican states. Southern whites seemed resistant to Obama’s appeal, voting 68% to 32% for McCain. Even so, Obama managed to peel off North Carolina and Virginia the fastest-growing states in the South outside of Texas.

African-American voters increased their percentage of the electorate to 13%. In 2004, they accounted for 11% of voters. Although they were already strongly Democratic, Obama outperformed John Kerry among blacks by five points to the highest level of Democratic support. He won 95% of the black vote, compared to just 4% for McCain.

Significant Trend in Latinos

Obama also built up a big advantage among Hispanic voters. Over the last two elections, the Bush campaign was able to make inroads among Latinos. However, in 2008, Latinos came back to the Democratic Party. Hispanics were 9% of the electorate and Obama beat McCain by more than two to one. Obama led 67% to 31% among these voters, the best ever showing for a Democratic presidential candidate.

What’s more, Hispanic turnout was up in 19 states, including some that will have the average political observer scratching their head. The obvious places where Hispanic turnout was up were Arizona, Colorado, Nevada, and New Mexico. The not so obvious states were Indiana, Iowa, Michigan, Minnesota, Missouri, Montana, New Hampshire, North Carolina, North Dakota, Ohio, Pennsylvania, South Dakota, Virginia, West Virginia, and Wisconsin.

The Hispanic population is increasing all over the country; no longer are Hispanics only a significant voting bloc in Border States or states with big cities. This migration is shaking up the political map. For example, Hispanics can be credited as the voting group that swung Indiana. If no Hispanics had voted McCain, not Obama, would have carried Indiana.

Youth Vote Overrated?

At the age of 47, Obama will become one of the nation’s youngest presidents. He won partly because of an unprecedented level of support among young people and new voters. Obama was supported by those voters under 30 by an impressive 66% to 31% margin, much higher than in any previous election, as well as 68% of first-time voters.

This is an especially important statistic for one reason, also familiar to marketing professionals: picking a party for the first time is akin to picking between Diet Coke and Diet Pepsi. Once you become loyal to one, you usually stay loyal for some time.

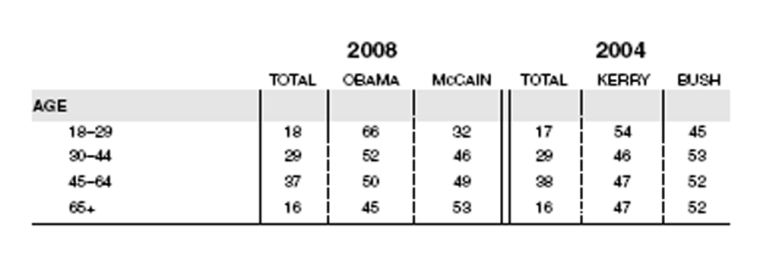

This year the gap between young and old increased a lot. Obama outperformed Kerry with all age groups except seniors. McCain retained the Republican advantage among seniors but lost among the middle-aged, who had supported Bush in 2004. Obama got just over half of the vote among those 30 to 64 years old.

The consistent growth in the margins among the youth vote over the last eight years is one of the best signs for the Democratic Party in terms of their push for realignment. In 2000, Gore beat Bush by a couple of points among voters aged 18 to 29. In 2004, Kerry beat Bush by nine points in this group. And in 2008, Obama beat McCain by 34 points, 66% to 32%.

Young voters are more diverse racially and ethnically than older voters and are growing more so over time. Just 62% of voters under 30 are white, while 18% are black and 14% Hispanic. Four years ago, this age group was 68% white; in 2000, nearly three-quarters, 74%, were white. They are also more secular in their religious orientation and fewer report regular attendance at worship services, and secular voters tend to vote Democratic.

At the same time, it’s important not to overstate the significance of the youth vote in Obama’s victory. In spite of the expectation of a significant increase in voting among young people, the youth share of the vote was 18% of the electorate this year, just one percentage point more than in 2004. And while almost a quarter of Obama’s vote was under 30, 77% was over 30. To hammer this point home, consider this stunning fact: if no one under the age of 30 had voted, Obama would have won every state he carried with the exception of two: Indiana and North Carolina.

New Voters Mattered to a Point

The Obama campaign did really well in their effort to increase their support among new voters. One in ten of those voting in 2008 did so for the first time, the same proportion of the electorate as in 2004. But they were quite different in their vote preference. A huge majority of new voters supported Obama by 69% to 30%. This compares to just a seven point advantage that the Democrats had in 2004 when Kerry won by 53% to 46%.

Two-thirds of new voters were under 30, and one in five was black, almost twice the proportion of blacks among voters overall. And nearly as many new voters are Hispanic, about 18%. Almost half were Democrats, and a third called themselves Independents.

Gender Gap Lives

Obama made a strong showing among women, winning them by 13 points, 56% to 43%, even more than the usual Democratic margin. This was partly because of the increased proportion of minority women voting for Obama. While Obama won women overall, and nonwhite women overwhelmingly, he performed slightly worse with white women in 2008 than Gore did in 2000. In that year, white women split their vote 48% for Gore to 49% for Bush. In 2008, McCain won the votes of white women, 53% to 46%.

When people discuss the gender gap they often concentrate on how much more Democratic women are than men. In a dramatic shift, Obama flipped men in this election in part because Obama narrowed the white male gap to 16 points, 41% to 57%. Not since Carter had any Democratic nominee earned more than 38% of the white male vote. This narrowing among a group of voters who account for 36% of the electorate allowed Obama to split the male vote overall, eking out a one point advantage, 49% to 48%, over McCain. This erased the advantage that President Bush enjoyed among men in 2004, 55% to 44%.

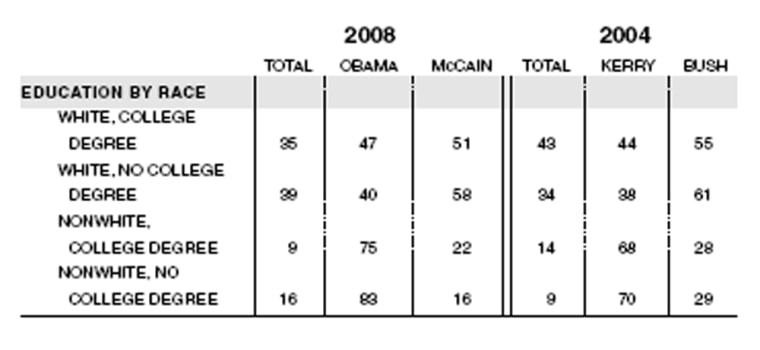

Obama Did Well Among the Better-EducatedObama ran stronger this year than Kerry did in 2004 among several voter groups that typically vote Republican.

Obama nearly tied with McCain among the 35% who are college educated white voters. They broke for McCain 51% to 47%, marking roughly a three point gain for Obama compared to Kerry’s 44% showing. There has been a trend for at least a decade, as more and more college-educated white suburban professionals have been moving toward the Democrats. The improved showing by Obama was particularly relevant in Virginia and Colorado, where white college graduates helped Obama win. Both states are in the top 10 states in terms of the highest rates of college education. They are the only two of those 10 states that Kerry lost in 2004.

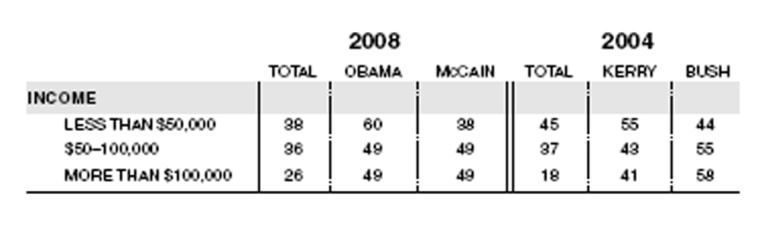

Obama outperformed Kerry among all income groups by at least five to eight points. Four years ago, George W. Bush carried voters nationwide with incomes over $100,000 by 17 points, 58% to 41%. In 2008, affluent voters split their votes evenly, 49% for Obama and 49% for McCain.

The biggest gains were among households with incomes over $200,000 where Obama improved the 2004 performance by 17 points. This was true even though McCain regularly harped on the fact that Obama was going to raise taxes on folks making over $200,000.

Obama’s persistent attention to the middle also paid off. When McCain sealed the nomination, his path to the White House seemed to be based on winning moderates and Independents. In the end, those who describe themselves as moderates, 44% of the electorate, voted for Obama by a huge margin, 60% to 39%. Obama also beat McCain among Independents by eight points, 52% to 44%, three points better than Kerry did in 2004.

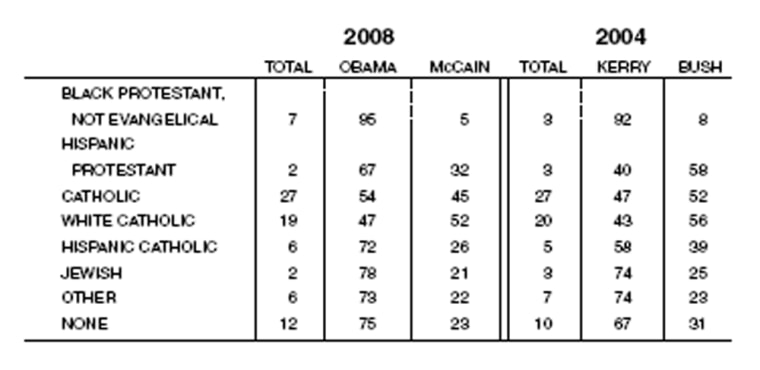

Catholics, about 26% of the electorate, and a vital swing group, were among the Republican-leaning groups that moved into the Democratic column for Obama, 54% to 45%. Obama also improved slightly among non-Hispanic, white Catholic voters, although McCain held a narrow majority, 52% to 47%.

There are several other interesting groups in Obama’s coalition: he won 83% of Hillary Clinton Democrats, 17% of 2004 Bush voters, and 62% of every voter who did not identify themselves as white Evangelicals. Despite worries among Democrats about Obama’s chances with Jewish voters, he won more than three-quarters of them nationally, a slight improvement over Kerry.

Republican Base

One group McCain held on to were white Protestant Evangelicals, who made up 23% of the entire electorate. This group voted three to one for the Republican despite attempts by Obama to reach out to faith groups. However, McCain received about five percentage points less support than Bush received four years ago.

McCain, 72, was the choice of just over half, 53%, of those in his peer group, senior citizens, coveted because of their turnout rate. Those 65 years and older were 16% of all voters, similar in number to those under 30.

Obama fared relatively poorly among white voters without a college education. He lost this group by 18 points, a small improvement over Kerry’s performance. John McCain courted workingclass whites, calling out repeatedly to “Joe the Plumber,” a symbol of these voters, and drew some of his strongest support from them, winning 58%. In fact, he even flipped a few counties in southwest Pennsylvania where the “Joe the Plumber” message may have resonated best. But the group’s share of the electorate dropped by four points and McCain’s margins were shy of the 23 points by which Bush won this group in 2004.

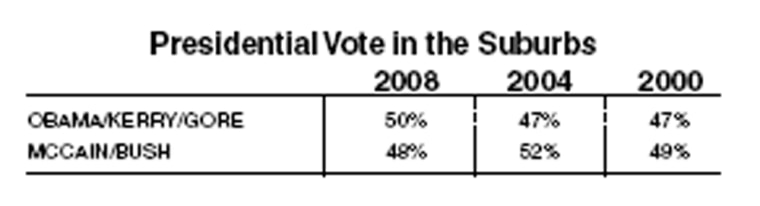

The Suburbs

The lynchpin of any realignment in American politics is the suburbs. The nation’s suburbs have sometimes been portrayed as lilywhite enclaves of the middle and upper classes, detached from the problems and diversity of the cities. The suburbs have also long been characterized as Republican strongholds, at least in presidential races, areas where the GOP overcomes usual Democratic margins in the nation’s big cities.

But none of those stereotypes about the nation’s suburbs are accurate anymore, if they ever were. In particular, the political geography of the suburbs is a battleground, not a partisan bastion.

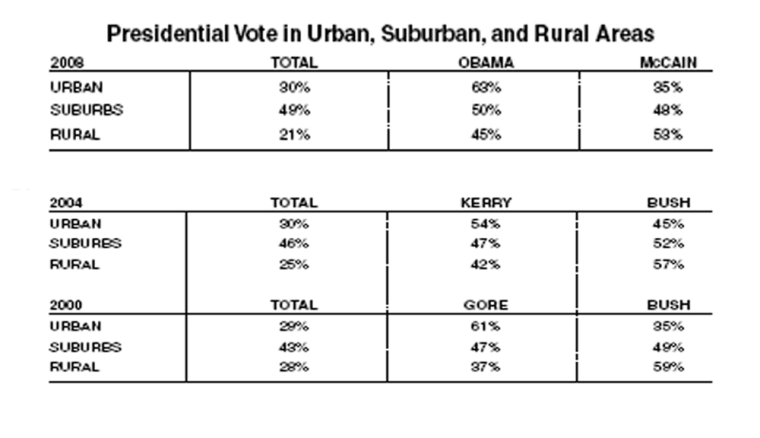

The battle for the White House in 2008 was decided, in large part, in the suburbs. Obama won the suburbs over McCain, if narrowly, the first Democrat to achieve that since Bill Clinton in 1996. Obama won 50% of the vote in the suburbs, while McCain took 48%.

That performance in the suburbs, matched with Obama’s good showing in the big cities (although not as good as some expected), was enough for victory. But Obama’s win in the suburbs was not a huge surprise. First, the suburbs have been fought over in the twenty-first-century presidential campaigns, with neither party holding a decisive edge for what is about one-half of all the votes in the country. Bush won the suburbs by only two percentage points in 2000 and only five percentage points in 2004.

The preelection polls in 2008 depicted a seesaw battle for the suburbs, with Obama holding a lead in the spring, but McCain taking the lead in mid-summer and holding that into September. But close to the election, several polls, including the National Suburban Poll for Hofstra University, showed Obama moving into the lead in the suburbs.

Obama won the big cities by a 63% to 35% margin, an overwhelming victory. That 28 point win was a substantial improvement over Kerry’s 54% to 46% victory in the urban areas in 2004, but it was only slightly better than Gore’s 61% to 35% win in the cities in 2000.

McCain did well in the rural areas, although again, not as well as past GOP candidates. He won 53% to 45%, certainly the poorest showing there for a Republican since 1996. McCain’s eight point margin trailed Bush’s 22 point edge in 2000 and his 15 point win in 2004.

Comparing results in the suburbs over time is a tricky business, because the suburbs have been a constantly shifting and expanding area over the past several decades.

In just about every red state Obama flipped or every blue state he won substantially, it was a flip in the suburban counties that led the way, whether one looks at the northern Virginia suburbs, which powered Obama’s victory in the Old Dominion to the Research Triangle in North Carolina to county flips in the I-4 corridor in Florida and the surrounding suburban counties in Denver, Colorado.

The building blocks for Obama’s victory in the suburbs were the same as those he used in the cities: he won big majorities among the young, those with college degrees, minority group members, and those who are not married. Obama won the votes of those age 18 to 29 by 20 points and those in their 30s by a 51% to 47% margin, compared to an eight point GOP margin among these suburbanites in 2004.

Obama improved his showing among both suburban men and suburban women by seven percentage points over 2004, but it was suburban women who moved firmly into the Democratic camp, 52% to 46%.

Two groups led this change: working women and women with children, particularly married women with children. Suburban working women were evenly divided in 2004, 49% to 49%, but Obama won them by 21 points, 60% to 39%. Married suburban women with children also pivoted in a major way: Obama won their votes by 52% to 48%, compared with Bush’s 17 point victory in 2004.

Religion played an interesting role in the suburbs in the 2008 election. Evangelicals did turn out in the suburbs, rising from 28% of the suburban voters to 36%. And they did back McCain, by a hefty 58% to 39% margin. But that was far short of the 66% to 33% edge Bush won among these suburbanites in 2004.

Obama improved the Democratic showing among many income groups, although the gain among those suburbanites making less than $50,000 a year was only four percentage points. Again, among

white suburbanites making less than $50,000, Obama actually did worse: he lost the group by six points while it split almost evenly four years before when Kerry lost by two points.

The inner and outer suburbs have also helped power the Democrats back into impressive majorities in both houses of Congress. Take a look at the map of Democratic House victories in both 2006 and 2008. Many of the seats they’ve won are in suburban areas of the country, from Florida’s 8th Congressional District in and around Orlando to Virginia’s 11th District that includes Fairfax County. The GOP slippage in the suburbs has been evident for some time.

Firing the Republicans

Identity politics is just one way to determine how Obama won. But forget gender, age, and ethnicity a minute and remember this election may have been decided by one, simple, four letter word: B-U-S-H . This election took place during one of the longest sustained periods of voter dissatisfaction in modern history. The vote was a verdict on the past eight years of Republican rule. Threequarters of Americans thought America was on the “wrong track” and two-thirds disapproved of Bush’s performance as president.

In 2000, voters who felt the country was headed in the right direction outnumbered those with negative assessments by two to one: just 31% said the country was on the wrong track that year. In 2004, 46% held that view. In this election, 75% of voters said the country was “seriously off on the wrong track.” This included majorities of key swing groups such as Independents and moderates. Among those who thought the country was off on the wrong track, Obama beat McCain 62% to 36%.

Only 27% approved of Bush’s job performance, while 71% disapproved. The last time a sitting president had an approval rating this low in an election year was 1952, long before the exit poll was invented. A Gallup Poll in February 1952 reported a 22% approval rating for Democrat Harry S. Truman. Truman did not run for reelection that year, but Dwight D. Eisenhower soundly defeated Adlai Stevenson, the Democratic Party’s candidate. Even in Utah, one of the nation’s most Republican state, a majority, 51%, disapproved of the job Bush was doing. This compares to 53% approval among Utah voters in 2004.

Bush’s job rating was an important factor in determining which states would turn red or blue. With the single exception of Missouri, which barely went for McCain, Obama won every state where Bush’s approval rating was below 35% in the exit polls, and he lost every state where Bush’s approval rating was over 35%.

McCain spent much of the campaign trying to disassociate himself from Bush. But Obama never let him forget his mostly loyal Republican record. McCain proclaimed in his final debate with Obama, “I am not President Bush. If you wanted to run against President Bush, you should have run four years ago.” While McCain may have said he would bring change, he failed to convince. When voters were asked whether they thought McCain would continue Bush’s policies or take the country in a new direction, half of them said McCain would continue on Bush’s path. And of those voters, nine in ten voted for Obama.

War in Iraq