When Julien Petillon wanted to see how long a salt marsh-dwelling wolf spider could survive underwater, he did the logical thing — he submerged them, and waited until they died.

Spiders are known for their resilience to being underwater, so it was no surprise to him that the dozens of Arctosa Fulvolineata in the experiment took almost 24 hours to grow still. What did surprise him is the dead-still spiders then came back to life.

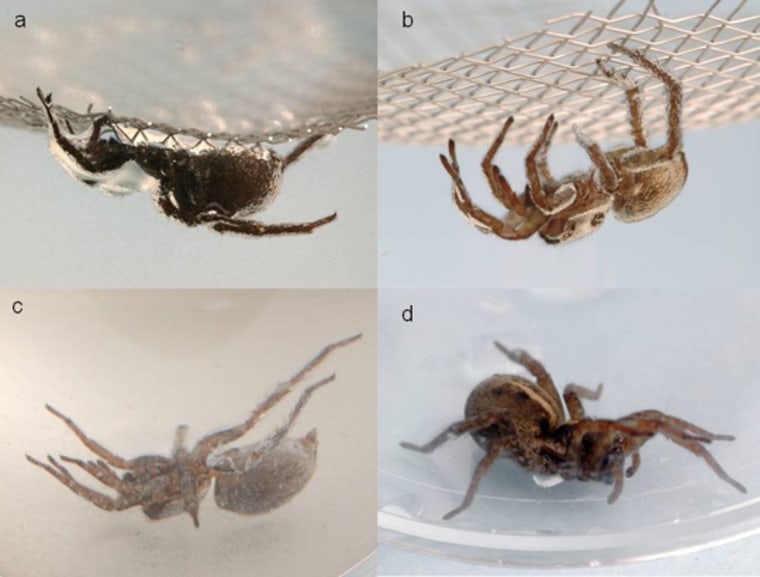

As they lay drying in Petillion's laboratory at the University of Rennes in France, something odd happened: the 'dead' spiders began to twitch. First one small movement, then another — before long the salt marsh spiders were skittering about as though nothing had happened.

"It was really a surprise," Petillon said. "We did not suspect the spiders could go into a coma."

But that's exactly what happened. In a paper published today in the journal Biology Letters, Petillion and a team of researchers report that A. Fulvolineata can survive up to 40 hours underwater by slipping into a brief suspended animation, switching its metabolism from aerobic to anaerobic when oxygen is in short supply.

Only a few A. Fulvolineata survived that long, but almost all withstood 16 hours of immersion without a scratch. Their close marsh-dwelling cousins Pardosa purbeckensis and the forest-living Pardosa lugubris didn't fare nearly as well, and showed no signs that they could come back from an unresponsive state.

"Many species of spider live in submerged habitats," Petillon said. "Most avoid flooding by climbing up in vegetation. A. Fulvolineata is the first we've seen that withstands flooding like this."

Petillon believes the 16-hours sweet spot of survival is no accident. In the salt marshes of northwestern France where A. Fulvolineata lives, flooding from high tide usually only lasts 8 hours or so. But on rare occasions marshes won't drain for two consecutive tidal cycles.

"I would not be surprised to see this in many other species," Todd Blackledge of the University of Akron in Ohio said. "A large number of spiders are ground-dwelling, and would be faced with similar challenges."

Spiders have used silk throughout their 400 million-year history, and many scientists suspect it first arose as a defense against water. By spinning a waterproof wall over the entrance to their burrows or dens, the animals could ride out floods and heavy rains. Modern spiders still exhibit this behavior too, using silken 'diving bells' to patrol lake bottoms, and to build homes in the crevices of coral reefs.

The wolf spiders Petillon and his team studied don't build webs, and spend very little time using their silk, which may account for their strange talent in dealing with regular inundation.