In 1994, President Bill Clinton received a letter from a White House visitor who noticed that none of the art that fills the presidential mansion was by an African-American. “Think about the impact that a tour of the White House has on African-American children, who travel great distances to see the home of our president, only to have it reinforced that they are invisible in many areas of America’s glorious history,” the letter read.

Soon afterward, in a move typical of Clinton’s dedication to diversity, Henry Ossawa Tanner’s 1885 oil, “Sand Dunes at Sunset, Atlantic City,” became part of the permanent collection of the White House. The painting depicts a landscape of whistling grass on white-hot sand under a pink sea of sky.

In unveiling Tanner’s painting, Hillary Clinton remarked that “talent always has the power to transcend prejudice.” Part of the legacy of both Clintons is that they gave access to diverse views that had previously been kept from the top levels of American government. The acquisition of Tanner’s painting for the White House is symbolic of the way Clinton was willing to use his power to appoint Cabinet and sub-Cabinet officials who expanded the visibility and power of minority groups.

As a candidate in 1992, Clinton promised a Cabinet that looked like America, a reference to the nation’s changing demographics and attitude toward diversity. For much of the nation’s history, when a president spoke of diversity in his Cabinet, he meant including men from different states, religions or European heritage. Clinton went well beyond that, extending the political definition of “a diverse Cabinet” to include race, gender, ethnicity and sexual orientation.

Where his predecessor, George Bush, could find only one qualified woman, one African-American and two Hispanics for his Cabinet, Clinton nominated three black men, a black woman and two Hispanic men to join nine white Cabinet nominees — three of them women. George W. Bush’s push for diversity in his own Cabinet this year can be seen as an affirmation of Clinton’s work on that front.

Different from the start

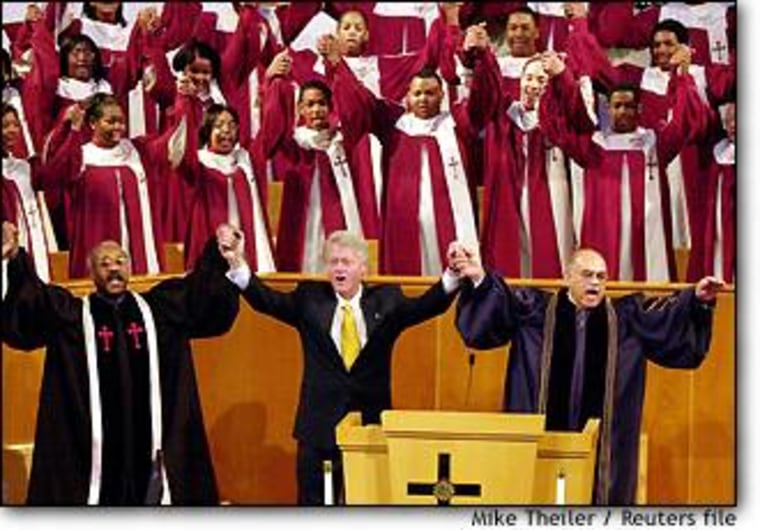

On the morning of his own inauguration in 1993, the Clintons attended the Metropolitan African Methodist Episcopal Church in Washington, the first time an African-American church had been used for the morning service traditionally held before the swearing in of a new president. Hours later, Maya Angelou, one of the country’s premier African-American poets, stood on Capitol Hill, the first time a poet had addressed an inaugural crowd in 32 years, her red AIDS ribbon flapping in the wind, reading a poem about hope.

John Jacobs, then president of the National Urban League, said shortly after the inauguration: “There’s a feeling that, for the first time in years, the nation has a leader who not only believes in diversity, but also is willing to champion it with youthful vigor and powerful communication skills.”

Jacobs’ early enthusiasm is shared somewhat by his successor at the Urban League, Hugh Price. “It’s a complicated picture,” Price said. “There were substantial accomplishments, and not trivial underachievement. The revival of our economy reached deep into our minority communities, deep into our inner cities, lowering unemployment rates among minorities dramatically.”

“Clinton’s appointments weren’t just symbolic, but showed a deeper understanding of the problems we face and an authenticity to his commitment to diversity,” Price said. “The appointments reverberated through the administration, influencing policy, allocation of resources and priorities.”

Discontent sets in

Despite the Clinton administration’s dedication to diversity, there remain plenty of people in America’s minority communities who became disillusioned by what they characterize as broken promises and compromises.

Indeed, Price rattled off a list of such complaints, including a criminal justice system “still riddled with prejudice,” the more than 40 million Americans still without health care and a presidential initiative on race that “lacked focus and quickly fizzled out during his impeachment hearings.”

Another diversity advocate who sees a very mixed record is Patricia Ireland, president of the National Organization for Women. While Ireland lauds Clinton for his diverse Cabinet selections - including the first female attorney general, the first female secretary of state and the second female Supreme Court justice - she says the appointments are leavened by disappointment in Clinton’s behavior revealed during the Monica Lewinsky scandal.

“It was disappointing to be reminded of that classic division that breeds sexism: that some women — your mother, Janet Reno, Madeline Albright — deserve to be respected, while others — Gennifer Flowers, Monica Lewinsky — deserve to be treated like Kleenex.”

On other issues, Ireland applauds the administration’s focus on violence against women and Clinton’s efforts to maintain affirmative action by “mending, not ending” it, but criticized the extent of his welfare reform. “His abandonment of poor women with welfare reform was disgraceful. He ended welfare without first discussing how to end poverty.”

The big picture

Winnie Stachelberg, political director of the Human Rights Campaign, a gay and lesbian political organization, says, “We too often look at disappointments.” She praises the president when looking at the big picture:

“He acknowledged there is a gay community with real concerns and talked about us in a way all Americans can understand, working those issues into the mainstream” of public discourse. She commends the increased funding for HIV and AIDS programs, the executive order banning antigay bias in the federal workplace and the appointment of openly gay and lesbian people, including the appointment of James Hormel as the first openly gay foreign ambassador after he faced a hostile Congress.

Clinton also created the position of a presidential liaison to the gay and lesbian community and overturned a Cold War-era policy that allowed the government to deny security clearances to gays and lesbians.

But Clinton disappointed the gay community when he compromised with the military on the “don’t ask, don’t tell” policy and signed the Defense of Marriage Act, restricting marriage to a union between a man and a woman. Two pending bills that sought to include language on sexual orientation, the Hate Crimes and Employment Non-Discrimination acts, languished on Clinton’s watch, but, Stachelberg adds, “not because this president didn’t support them.”

Suzette Brewer, the American Indian College Fund’s assistant director of public relations, also considers the big picture: “Ours is a country of many different interests. Not all problems can be solved at once, by one person. Clinton showed a sincerity and drive to make things different and better for more people.”

Leaders of Hispanic and Asian American organizations echoed praise for the Clinton administration’s opening of doors and the diversity of appointments, but noted the shortcomings of his race initiative. “Maybe we had our hopes raised too high,” said Victor Hwang, a managing attorney with the Asian Law Caucus. Howard Halm, president of the Asian Pacific American Bar Association, notes the symbolism of Clinton’s principle of diversity: “When I was growing up, the image of white guys from Arkansas was that they kept black kids from school. And now we’ve had a president from Arkansas who spent so much political capital trying to get more diverse people to the table. When young people see that, see that people like themselves have opportunities to assume high positions, see that a range of people can work together, it gives them hope,” Halm said.

Hope is difficult to quantify, but there are numbers that reflect Clinton’s mantra of diversity: In Reagan and Bush’s 12 years in office, of the 545 federal judicial appointments, 65 were women, 22 Hispanic, two Asian American and 17 African American. In Clinton’s eight years, of 366 federal judicial appointments, 104 were women, 23 Hispanic, five Asian American, one American Indian, and 61 African American, including Clinton’s appointment last month of Roger Gregory, the first black judge to the 4th Circuit Court of Appeals in Richmond, Va.

These changes, NOW’s Ireland notes, “don’t just come because of one person, but they don’t just come by the passage of time either.” Ireland, like others, will remember Clinton for his shortcomings, but also for ushering in government’s age of diversity, framing his legacy in part as one that “moved more people onward and upward.”