There have been raging debates over the years as to whether there is frozen water on the moon or not. Soon two NASA spacecraft, a lunar spycraft and a kamikaze probe, will help answer the question by peering into the permanent darkness of craters at the moon's south pole.

The new moon probes, the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter and the LCROSS impactor, are set to blast off this week on NASA's first mission to the moon in more than a decade. Any ice they discover could not only be used to quench an astronaut's thirst, but also to help fuel rockets for adventures beyond the moon.

All moon rocks collected so far suggest that its surface is bone dry, with any water that might come from impacting comets baked off by the sun, except perhaps for a few water molecules trapped in volcanic glass beads.

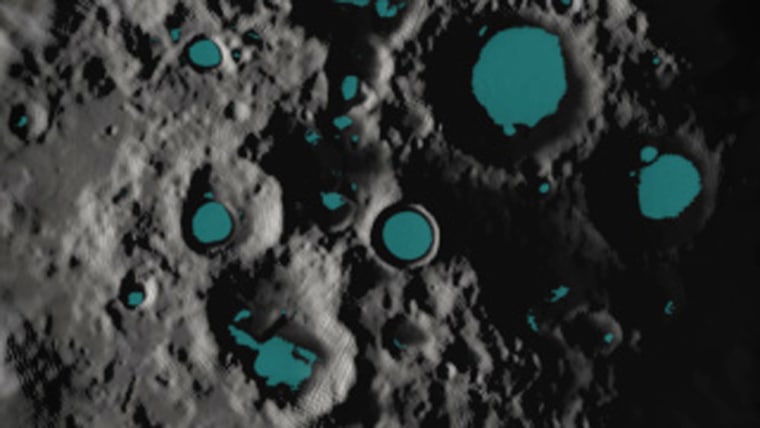

Still, there are deep craters at the moon's poles that have received no sunlight for 2 billion years or more, and in the cold of these permanent shadows — minus 328 degrees F (minus 200 degrees C) — researchers have suggested ice might have survived, explained Anthony Colaprete, principal investigator on NASA's LCROSS, short for the Lunar Crater Observation and Sensing Satellite.

NASA moved the launch the two moon probes from Wednesday to no earlier than Thursday to give the shuttle Endeavour another chance to lift off. The shuttle's launch was initially set for June 13, but was postponed until Wednesday due to a hydrogen gas leak. The leak recurred during Wednesday's second try, forcing shuttle managers to postpone Endeavour's launch until July.

Where is it?

Controversial evidence for whether there is water on the moon began appearing in 1996 with the Clementine probe, a joint Pentagon-NASA project. Radar scans of the lunar surface reflected back the kind of signals at the south pole that one might expect of ice and other frozen compounds.

However, later studies using the Arecibo radio telescope in Puerto Rico revealed similar reflections "even from areas exposed to sunlight, places too warm for water ice to survive," Colaprete said. This suggested the reflections that Clementine saw might have come not from water but from piles of rocks.

But in 1998, NASA's Lunar Prospector also detected hints of water, this time at both poles. Its instruments analyzed neutrons absorbed by a variety of elements on the moon's surface, including hydrogen. With this device, Lunar Prospector discovered hydrogen concentrated at the moon's poles, which scientists conjectured might have come from water molecules, each of which contains two hydrogen atoms. Researchers speculated the moon's poles could hold as much as 3 billion metric tons of ice.

The problem is that Lunar Prospector could only measure hydrogen, and not what matter the hydrogen was in. Instead of ice, the hydrogen might come from water bound up in clays, or protons from the solar wind, or the kind of carbon-laden molecules from comets that might have been part of the organic soup that life developed from on Earth, "or a mix of all those things," Colaprete said.

The upcoming LCROSS will crash two probes into the moon. Its partner probe, the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter, will map the moon from orbit and work with other ground and space-based assets to scan the LCROSS impacts.

By analyzing the plume, scientists hope to answer once and for all whether there is water there.

The icy cold truth

Any ice there might be on the moon could be key to the future of humanity in space. Although it could supply water for colonists to drink or grow food, more importantly, it could get split up to make hydrogen and oxygen for fuel for rockets.

"It costs about $10,000 to $15,000 per pound to launch something in the space shuttle, and there are about 8 pounds of water to a gallon, so we're talking about $100,000 to bring a gallon of water to low Earth orbit," Colaprete said. "If we can use the lunar poles as a resource, we could use them as staging bases to go elsewhere on the moon, or beyond the moon, or beyond Mars or Europa or elsewhere we'd want to go. You wouldn't have to bring up millions of gallons of fuel, you could produce it on the moon."

In addition, lunar ice might have survived untouched for billions of years, so it could "serve as a fantastic time capsule into the past," Colaprete said. "This is ice that could date back just as the Earth and moon and inner solar system as a whole were evolving, what kind of organic molecules might have been delivered to Earth. What hits the moon also hits the Earth."

If there is ice there, LCROSS could also show what form it is in — whether it is smoothly spread out in small grains across the crater, or in chunky patches. This could make a difference in how the ice is mined — whether astronauts simply scoop it up anywhere or have to go hunting for patches.

"The results we'll get could be critical for determining how we explore and make use of the moon," Colaprete said.

This report was updated by msnbc.com.

More on moon exploration | lunar ice