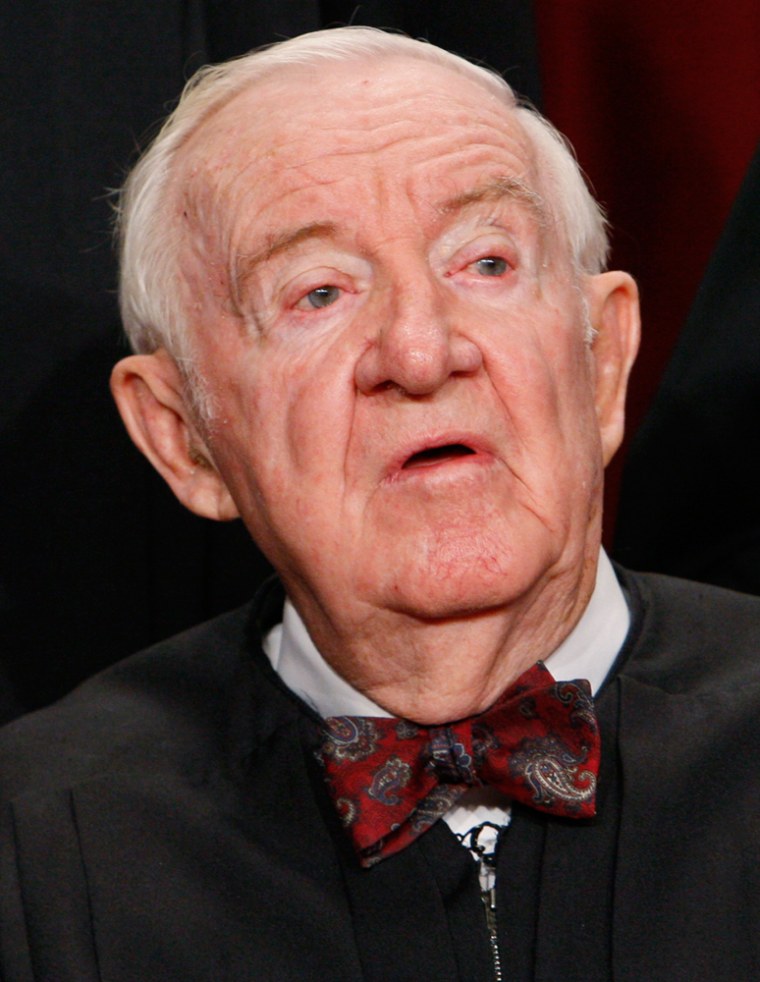

Around here, one of the most powerful men in the nation is known as plain old John Stevens — courteous bridge player, early-morning regular at the country club's tennis courts, a quiet and spry condo neighbor who checks his weight in the gym before heading off for his daily swim.

But those who cross paths with him in his second home of South Florida have the same question as the president of the United States, the leadership of Congress, the abortion rights combatants, the disgruntled conservative legal activists and the grateful civil libertarians, all of whom know him as Justice John Paul Stevens.

"Do you think he's going to retire?" asks his friend Raymond A. Doumar, an 83-year-old lawyer who met Stevens years ago waiting for a tennis match.

Stevens, who turns 90 later this month, isn't quite ready to say. "I can tell you that I love the job and deciding whether to leave it is a very difficult decision," he said in an interview. "But I want to make it in a way that's best for the court."

That would mean a decision sooner rather than later, in time for the nomination and confirmation process to be completed before a new term begins in October, he said. He acknowledged that he had told a reporter early last month that he would decide in about 30 days, but laughed that he hoped "that wasn't being treated as a statute of limitations."

His departure will hand President Obama his second chance to leave a lasting mark on the 9-member Supreme Court. "I will surely do it while he's still president," said Stevens, who plans to leave either this year or next.

If he stays past this term, Stevens will remain on a course to become the oldest and longest-serving justice ever. Paradoxically, he is also among the court's least-known members; in one poll taken last summer, only 1 percent of Americans could summon his name.

His departure, whenever it comes, will mark a significant shift in the workings of the politically divided court. Obama surely would choose a nominee from the left to replace him, so the ideological balance would not change.

But Stevens's lack of recognition nationally stands in direct contrast to his prominence on the court. For nearly 15 years, he has served as the leader of the court's liberal wing. His ability to find common ground with the court's justices in the middle -- former justice Sandra Day O'Connor and Justice Anthony M. Kennedy -- has led to groundbreaking decisions in favor of gay rights, restrictions on the death penalty, preservation of abortion rights and the establishment of a role for the judiciary in the nation's terrorism fight.

His departure would mark a generational change, as well, the removal of a link not only to the court's past but to the country's.

Stevens was in the stands, as was Franklin Delano Roosevelt, when Babe Ruth hit his "called shot" home run in the 1932 World Series. He is the only justice who was around for the start of the Great Depression, or who lived through Prohibition. He cracked Japanese code during World War II.

His experiences pop up in opinions. This term brought a reference to "Tokyo Rose," and in the past he chided his colleagues as being "unduly frightened" by videotape of a high-speed car chase. "Had they learned to drive when most high-speed driving took place on two-lane roads rather than on superhighways," they would not have been so shocked, he wrote.

"In a broad sense, the court's decisions help to tell, and record, the nation's history," said Gregory G. Garre, who served as solicitor general under President George W. Bush. "There is often an added sense of legitimacy, and even color, when the justices write about the history that they actually lived through. And it's amazing to think of all the history that Justice Stevens has lived through."

There are plenty of others who have lived through a lot of history along the Galt Ocean Mile, the beachfront strip Stevens has made his cold-weather home for more than 25 years. He and his wife, Maryan, live in the fortress of concrete and stucco 1960s and '70s high-rises, behind tropical landscaping, fountains and fake waterfalls.

The Atlantic Ocean is on one side, and on the other, the dichotomies that mark South Florida beach life: Ocean Hyperbaric Neurologic Center is just a few doors down from a thatched-roof tiki bar; an osteoporosis clinic is wedged between a nail salon and a beach sandals factory outlet.

He heads for Florida when the court is not hearing arguments, taking his paperwork outside and remaining in touch with the office by computer, while pursuing a fitness regimen that includes a daily swim and singles tennis three times a week.

Despite 35 years on the bench, he is anonymous on the beach. "That's one of the things I enjoy about it," Stevens said.

"I'm on the beach, I'm outside, that's awfully nice," Stevens said. "Of course, I have my computer, I'm still doing the same work. It's not really a vacation." Stevens still writes the first draft of all majority opinions or dissents that bear his name, he said.

He may be anonymous to the lady at the drugstore, who kindly helped him bandage a recent cut "not because she knew who I was, but because she was just being nice," but others are aware.

No one bothers him at the bridge club, manager Jeanni Blume said, but they notice. "Oh, they act like real ladies and gentlemen when he walks in," said Blume. Apparently, competitive spirit runs high: A large sign at the club pleads "Be Polite. Be Friendly."

Conflicts are fairly frequent, she said, and remembered that after refereeing one dispute, she walked by Stevens's table to say, "I really should let you handle this."

Stevens laughs at the idea that the bridge players straighten up when he's around. "If that's true, it's because of my wife. She's far more popular at the bridge club," he said.

His friend Doumar remembers that when he met Stevens at the country club, it took him awhile to connect the name -- "John Stevens" -- with the proffered profession -- "Washington lawyer" -- and then, finally, "judge." "I finally said, 'John Paul Stevens? Oh my God, Justice, I'm sorry,' " Doumar recalled.

"He's the most unassuming person I've ever met," Doumar said. "He has no airs about him -- he never goes to the front of the buffet line, he always waits his turn."

Dianne Marie Amann, a former Stevens law clerk who has written extensively about her old boss, said his life outside of Washington has been important.

"I think one of the secrets of his longevity on the court is the very vibrant personal life he has maintained outside the court," said Amann, who is a law professor at the University of California at Davis. "Having maintained a place where he can be something other than an associate justice has served him well."

Stevens has cordial relations with the other members of the court, but doesn't frequent the Washington party circuit and gives few speeches outside an annual talk to the judges of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 7th Circuit in Chicago. That is where he grew up, and he was a circuit judge there when President Gerald Ford tapped him for the Supreme Court in 1975.

It is notable that he is one of the last justices whose ideology was not a major part of the calculus that led to his nomination. He was confirmed unanimously by the Senate only 19 days after his nomination.

The lack of controversy may be one reason he has never been firmly established in the public's mind. And for a time, his votes fit a moderately conservative pattern, though he often struck out on his own in the legal reasoning he used to get to a result.

"He was known mostly as being idiosyncratic for many years," said University of North Carolina law professor Michael Gerhardt, a student of the court. "But as time went on, roughly in the last decade or so, he made a very conscious, very deliberate decision to take on a leadership role."

As the senior justice, Stevens has the power to decide which justice writes the opinion when the chief justice is not in the majority. It is that ability to shape historic outcomes, rather than a distinct judicial philosophy or strength of personality, that has marked Stevens's tenure, according to Notre Dame law professor Richard Garnett, a law clerk to former chief justice William H. Rehnquist.

"I wonder if a big part of it is luck," Garnett said. "He was the senior justice for a bloc on the court, the liberal bloc, that was stable for an unusually long period of time. And by being the senior guy, he was able to control the crafting of the court's judgments in a bunch of hot-button issues."

Stevens wrote most of the court's decisions that struck the Bush administration's policies on the rights of detainees held in Guantanamo Bay, Cuba. But he was willing to give up the opinion-writing in other major cases -- to O'Connor on affirmative action, to Kennedy on gay rights -- to preserve a majority.

"The institution means a great deal to him -- I'd say more to him than his own personal legacy," Gerhardt said. But lately, the victories have been fewer. "The institution is not going in the direction he thinks it should," Gerhardt said.

That was clear earlier this year when he was on the losing side in Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission, which changed the rules on the role corporations and special interests can play in elections. Stevens delivered a stinging 90-page dissent, saying his conservative colleagues in the majority had an "agenda" and that they ignored "the overwhelming majority of justices who have served on this court."

Stevens read part of the dissent -- in an uncharacteristically shaky voice -- from the bench, and some viewed it as something of a valedictory, or at least a confirmation that he was leaving.

The justice said too much is being read into his frustration.

"I'm always disappointed when people don't agree with me, but those rulings don't figure into my decision on whether to call it quits," Stevens said. "My colleagues are wonderful people. I miss Justice [David H.] Souter, but he has a wonderful replacement" in Justice Sonia Sotomayor.

Obama, of course, nominated Sotomayor, and the White House already has begun preparing to choose Stevens's successor. He said the president, who has taught constitutional law, is uniquely qualified for the role.

Obama is a "very competent president" to make choices for the Supreme Court, Stevens said. Perhaps the best, he added, "since Gerald Ford."