A debate is brewing in the bat research community over one of the winged mammal’s senses.

No, it has nothing to do with vision. Despite the tiny eyes and nocturnal lifestyle, none of the roughly 1,100 bat species is blind.

“All bats can see and all bats are sensitive to changing light levels because this is the main cue that they use to sense when it is (night time) and time to become active,” said Paul Faure, of McMaster University’s Bat Lab.

Instead, researchers can’t agree on a certain aspect of the mammal’s sonar sight, called echolocation.

To track down prey, avoid predators and find their way home in the dark, most bats depend on echolocation. They broadcast high-pitched sonar signals and listen for the echoes of sound waves bouncing off objects they’re looking for or obstacles in their path. Bats’ brains then process the auditory information within those echoes as visual maps.

Scientists know a lot about the finer points of how echolocation works, but they differ on whether that sense evolved before or after bat’s ability to fly.

“Some question whether echolocation 60 million years ago would’ve been too sophisticated,” said Brock Fenton, of the University of Western Ontario.

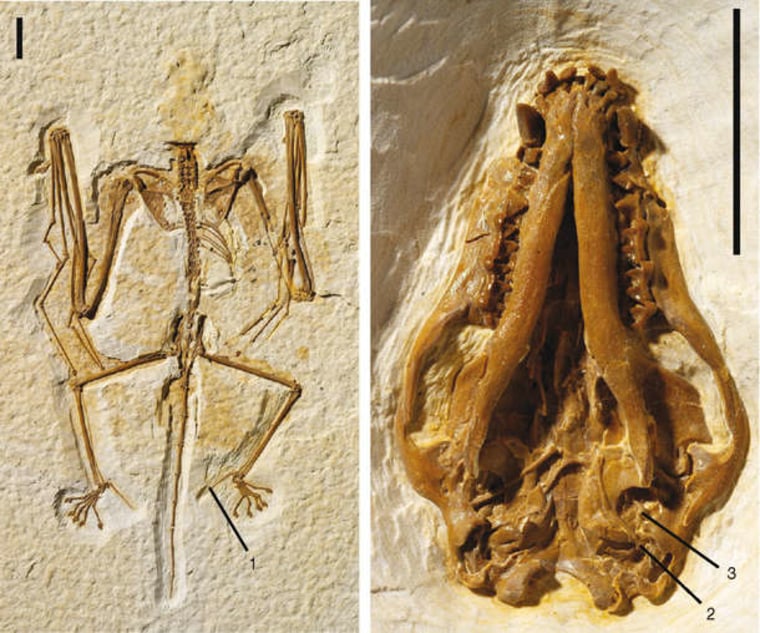

The scientists who discovered Onychonycteris finneyi, the oldest known bat fossil (above), concluded that the prehistoric species could fly but that the sonar sense didn't evolve until later.

However, Fenton and colleagues recently published a study in Nature that has reinvigorated the echolocation-versus-flying timeline debate.

Using 3-D scans from multiple bat species, Fenton identified a specific anatomical feature near the animal’s voice box that facilitates echolocation.

“In any echolocating bat, the stylohyal bone is at least physically touching or even fused to the tympanic bone,” Fenton said.

When scientists examined O. finneyi, as part of the study, their results suggested that the ancient species may have also shared that same echolocating bone structure.

“The problem is," Fenton told Discovery News, "it’s a pancake fossil,” meaning it’s difficult to distinguish the exact bone structure since the artifact became flattened over time.

Whether flight preceded echolocation or not, echolocation opened up an untapped prey resource by allowing bats to hunt insects at night without competition from similar daytime predators. Otherwise, their long-term survival would’ve been far more dubious.

Though echolocation is a relatively primitive trait, existing since at least 50 million years ago, researchers are still discovering new complexities about the sonar system.

“Bats can specially tailor their signal to get the information they want (such as targeting prey, locating a predator or finding their roost),” Fenton said. “It’s the same as listening to a person who’s good at singing.”

But since bats also have perfectly good vision, what they see can sometimes interfere with what they hear.

“We know that visual information can override echolocation information even when the echolocation information contradicts the visual information,” Faure from McMaster University said.

For instance, a captive bat in a darkened room might fly into a window since it sees light coming through pane as an escape route, although echolocation sonar tells it there’s an obstacle in the way, Faure explained.

While the question of whether bats are blind has long since been answered, understanding the origin of echolocation and how they interpret that sonar sense simultaneously with sight are just two of the myriad mysteries left to solve about the vast Chiroptera order of bats.

“That’s the good thing about bats,” Fenton said. “Every time you go back and look at them, you find something else.”