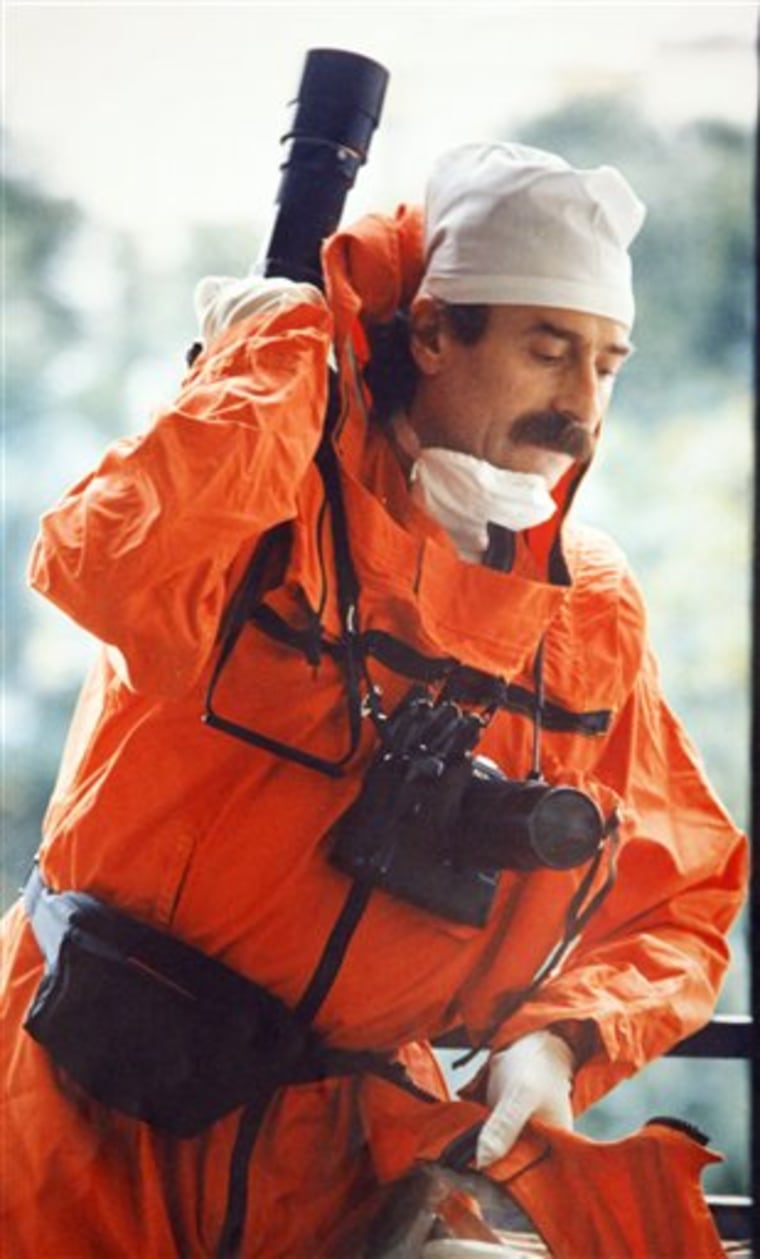

Wearing a lead protective suit and placing his cameras in lead boxes, photographer Igor Kostin made a terrifying and unauthorized trip to the Chernobyl danger zone just a few days after a nuclear power plant reactor exploded in the world's worst atomic accident.

He came back home with nothing to show for his determination to document the crisis — the radiation was so high that all his shots turned out black.

But Kostin returned, and his work along with that of a handful of other daring photographers was critical to the world's understanding of a catastrophe that Soviet authorities were reluctant to admit.

A quarter-century after the April 26, 1986, blast that spewed radioactive fallout over much of Europe, Kostin's memories are as vivid and terrifying as any photo. They carry an added chill as Japan struggles to bring its radiation-spewing Fukushima Dai-ichi nuclear plant under control after last month's earthquake and tsunami triggered the world's worst nuclear disaster since Chernobyl.

On his first trip into the Ukrainian danger zone, the photographer for the Novosti Press Agency wangled his way aboard military conveyances. He recalls hearing alarmingly high radiation readings from the pilot:

"A tightly closed armored troop carrier, a helicopter floor covered with lead, windows closed tightly. Ruins of the reactor on the right. A pilot's voice — '50 meters to the reactor, 250 Roentgen'. I opened the window and was shooting. It was a stupid thing."

Those were the shots that showed nothing.

But nine days after the blast, authorities allowed Kostin and two other shooters — Valery Zufarov of TASS and Volodymyr Repik — to get terrifyingly close.

Kostin, now 74, was with a group of "liquidators," soldiers who had been pressed into service to battle the disaster.

He climbed to the roof of the building next to the exploded reactor, firing off frames to record the soldiers who were frantically shoveling debris off the ruined structure's roof.

He had to shoot fast.

"They counted the seconds for me: one, two, three ... As they said '20' I had to run down from the roof. It was the most contaminated place, with 1,500 Roentgen per hour. The deadly dose is 500 Roentgen," Kostin told The Associated Press. "Fear came later."

"It was like another dimension: ruins of the reactor, people in face masks, refugees. It all resembled war," Kostin said.

Kostin said that being a photographer was like being a hunter. But after his Chernobyl ordeal, "now I know what a victim feels while being followed by an invisible, inaudible and thus even more dangerous enemy."

Because of extreme radiation levels, the soldiers, in eight-man teams, worked for no more than 40 seconds on the roof of the destroyed reactor's building. That means they had to run upstairs onto the roof wearing lead suits, pick up a shovelful of debris and throw it into the huge hole in the roof. Most of them took no more than one to three shovelfuls.

Kostin is the best-known of the Chernobyl disaster photographers, but Anatoly Rasskazov was the first. As a staff photographer for the plant, he was allowed in on the day of the explosion. On April 26, at noon — hours after the blast — he made a video of the destroyed reactor and submitted it to a special commission working in a bunker close to the plant, said Anna Korolevska, deputy director of Chernobyl museum in Kiev.

Rasskazov's photos were submitted to the commission by 11 p.m. on the same day — and were immediately seized by the Soviet secret police.

Only two of Rasskazov's photos were published in 1987, without mentioning the author's name.

Rasskazov died last year, aged 66, after suffering for years from cancer and blood diseases that he blamed on the radiation.

On May 12, 1986, more than two weeks after the explosion, the leading Soviet daily newspaper Pravda published its first photograph from the site for the first time, shot three days earlier from a helicopter by Repik.

"If I had been ordered now to get aboard and go, I would not have gone — you might have easily died there for nothing," said the 65-year-old Repik.

Zufarov died in 1993, aged 52, of Chernobyl-related disease. His first pictures were made from a helicopter 25 meters above the plant.

Kostin's work in the days after the blast and in subsequent years on Chernobyl won him a World Press Photo Prize. It also exposed him to heavy levels of radiation and he has undergone several thyroid operations over the years. Thyroid cancer is one of the most widespread consequences of the blast.

His photos provide a permanent record of calamity: of the hasty construction of a "sarcophagus" over the destroyed reactor area, of deformed children born dead after the blast, of living children suffering thyroid cancer, of liquidators suffering leukemia.

The images still haunt him.

"Where did I see that? In a movie? Or when the war (World War II) started when I was five?" he said.