Black holes will eat just about anything, and now astronomers have confirmed that stars are on their menus.

Observations from three space-based X-ray telescopes over about a decade provide the first solid evidence of a star being torn apart and partly swallowed by a black hole.

Astronomers already have plenty of evidence for black holes consuming gas that swirls inward and is superheated, generating radiation in many wavelengths from radio to visible light and X-rays. They have long assumed that whole stars could be torn apart by the gravitational tug of a black hole, but proof has been elusive.

The new evidence confirms other suggestive observations that such dramatic events do occur.

Wrong way

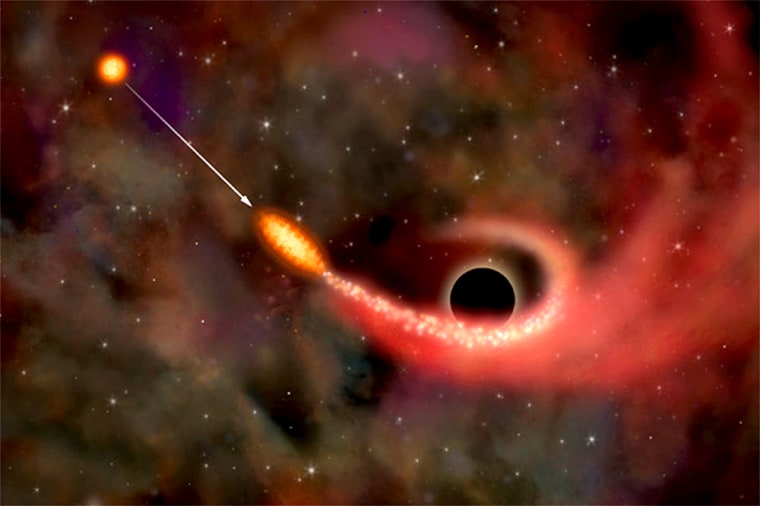

In a close interaction with another star, the ill-fated star was gravitationally booted onto a fateful trajectory near the center of a distant galaxy, astronomers said Wednesday. As it approached a supermassive black hole that packs as much mass as 100 million suns, the star was stretched by tidal forces similar to those that raise the oceans on Earth.

"Stars can survive being stretched a small amount," said study leader Stefanie Komossa of the Max Planck Institute for Extraterrestrial Physics in Germany. "But this star was stretched beyond its breaking point."

The supermassive black hole anchors a galaxy called RX J1242-11. It is about 700 million light-years away. The star was about the size of our sun. It was ripped to shreds in just hours or days.

After it was pulled apart, some of the star's gas was lured into the black hole. It was heated to millions of degrees just before being swallowed, releasing energy equal to when a star explodes in a supernova event. The astronomers detected the brilliant flare of X-ray activity.

"Now, with all the data in hand, we have the smoking-gun proof that this spectacular event has occurred," said Günther Hasinger, also of the Max Planck Institute.

Hasinger likened the tidal stretching to what would happen if he jumped into a black hole feet-first. Because gravity decreases with distance, his feet would be tugged with greater force than his head. "I would feel a force that is trying to rip me apart," he said.

The flare was brighter, at its peak, than all the stars in the galaxy combined, the researchers said.

The results were announced at a NASA press conference Wednesday afternoon and will be detailed in the Astrophysical Journal.

Bad manners

Black holes are known to be sloppy eaters. They digest only a small amount of what's on their dinner plates, spitting the rest back into space. In this case, only about 1 percent of the star was ultimately swallowed, the research team concluded. The rest of the star's gas was flung into the galaxy by the momentum and energy of the whole interaction, including the radiation kicked up by the portion of gas that did disappear.

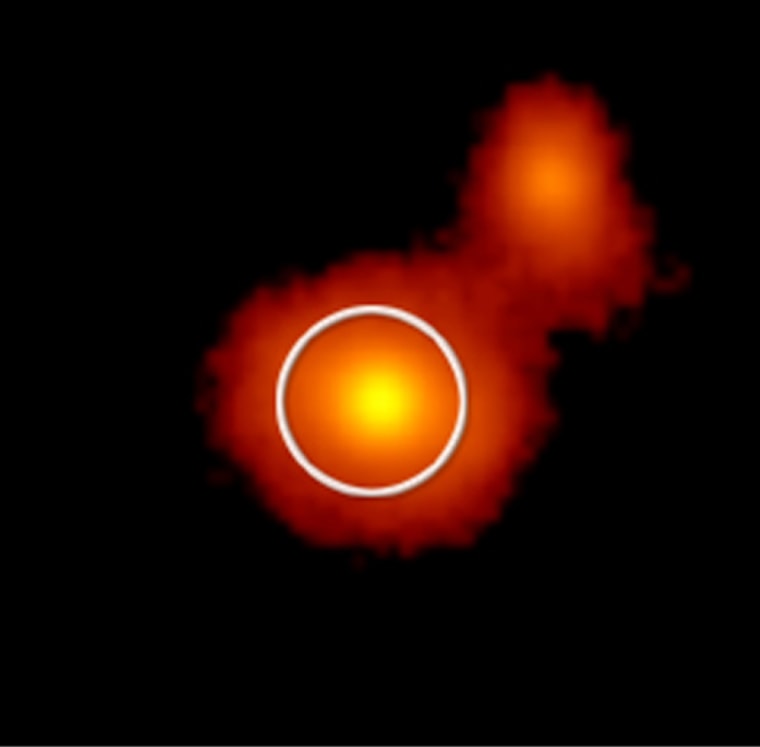

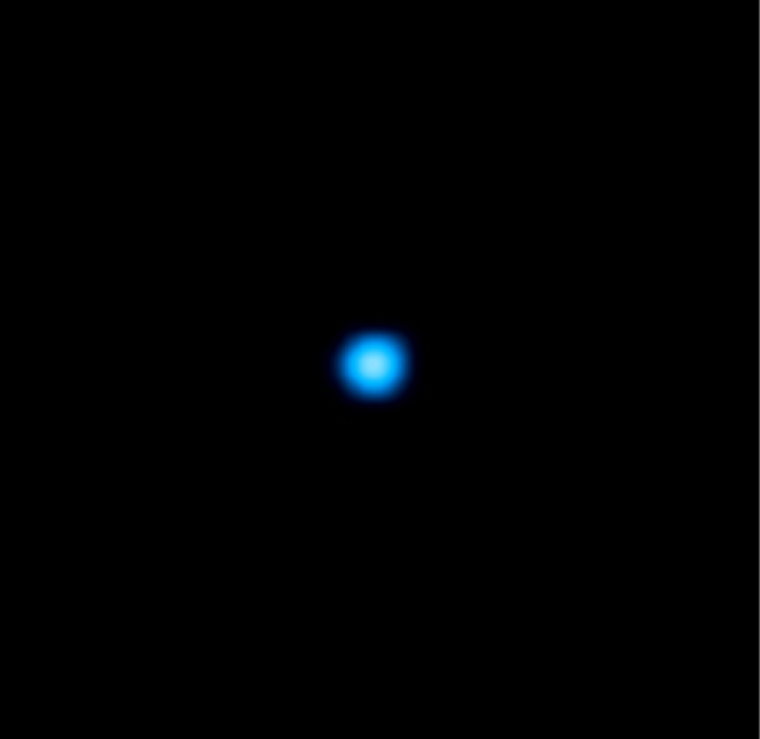

The new observations were made with NASA's Chandra X-ray Observatory and the European Space Agency's XMM-Newton when the flare had settled down considerably. The research team had first examined earlier images made by the German Roentgen satellite, also known as ROSAT, from 1990 and 1992 when the flare was at its brightest.

The flare's intensity decreased by a factor of about 200 since then. That is consistent with a star being torn apart to feed the black hole, Komossa explained, as opposed to a smoother flow that would have occurred if the black hole were consuming a giant gas blob of similar mass.

This decline of activity over time also suggests the flare was not part of the normal, prolonged feeding activity that occurs around other supermassive black holes called quasars.

At the height of the flare, the black hole swallowed the equivalent of one Earth every 10 minutes.

Similar flares have been observed in other galaxies. But none had been recorded in such detail, the researchers said.

Black holes can't be seen, because once matter or light is trapped in one, it cannot escape. Astronomers infer the existence of black holes by noting flare activity around them and also by measuring the speed with which nearby stars and gas orbit. Just before disappearing into a black hole, material is accelerated to nearly the speed of light.

Chandra showed that the outburst came from the center of the galaxy, where the suspected black hole sits. The XMM-Newton observations revealed other fingerprints of a black hole, ruling out other physical explanations for the flare-up, the scientists said.

"I think this is very strong evidence that stars are being ripped apart occasionally by supermassive black holes," said Alex Filippenko, a professor at the University of California at Berkeley who was not involved in the work.

Similar observations in other galaxies would help theorists gain a better understanding of how black holes work and the important role they play in galaxy formation. Filippenko said scientists could now begin to set constraints on how frequently these stellar destructions actually occur and study how black holes grow and evolve with time.

No danger

Our own Milky Way Galaxy harbors a black hole that packs between 3.2 million and 4 million solar masses. It is a relatively quiet black hole compared to many, reflecting in part the maturity of the galaxy and, theorists say, a lack of nearby material on which to dine.

Komossa's team said black holes rarely rip stars apart in the fashion they've witnessed, a so-called stellar tidal disruption. It ought to occur about once every 10,000 years in a typical large galaxy harboring a black hole. Given that there are thought to be billions of these supermassive black holes in the universe, future observations should be able to detect the events regularly.

If a star were similarly destroyed at the center of the Milky Way, it would generate an X-ray burst 50,000 times brighter than any other X-ray source in the galaxy.

Our solar system is about 25,000 light-years from the galactic center. So a stellar tidal disruption there would not pose any danger to Earth, the scientists said.

Kim Weaver, an astrophysicist at NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center, said the scenario proposed by Komossa and Hasinger is not the only possible outcome for stars that approach black holes, though it likely describes the recent observations.

In other cases, Weaver said, stars that are not close enough to a black hole to be torn apart could be instead spun up to 60 times their normal rotation speed. In other situations, "a star could actually be swallowed whole," she said, and there would be little or no radiation to mark the event.