The calls have reached a point of repetitive regularity for civil rights lawyer Gadeir Abbas: A young Muslim American, somewhere in the world, is barred from boarding an airplane.

The exact reasons are never fully articulated, but the reality is clear. The traveler has been placed on the government's terror watchlist — or the more serious no-fly list — and clearing one's name becomes a legal and bureaucratic nightmare.

On Monday Abbas sent letters to Secretary of State Hillary Clinton and FBI Director Robert Mueller requesting assistance for his two most recent clients. One is a resident of Portland, Ore. who is trying to fly to Italy to live with his mother. The other, a teenager and U.S. citizen living in Jordan, has been unable to travel to Connecticut to lead prayers at a mosque.

"All American citizens have the unqualified right to reside in the United States," Abbas wrote Monday in a letter to secretary of State Hillary Clinton seeking a change in status for the client in Jordan.

Abbas, a lawyer with the Council on American-Islamic Relations, tries to piece together the reason why a client has been placed on the list. Perhaps a person has a similar name to a known terrorist. Maybe their travels to Yemen or some other Middle East hot spot have garnered suspicion. Maybe they told the FBI to take a hike when they requested an interview.

Ultimately, though, the reasons are almost irrelevant. From Abbas' perspective, the placement on the no-fly list amounts to a denial of a traveler's basic rights: U.S. citizens can't return home from overseas vacations, children are separated from parents, and those under suspicion are denied the basic due process rights that would allow them to clear their name.

Abbas describes the security bureaucracy as Kafkaesque, a labyrinthine maze of overlapping agencies, all of which refuse to provide answers unless they are threatened with legal action. One lawsuit is still pending in federal court in Alexandria, Va. That case has followed what has become a familiar pattern: Abbas either files a lawsuit or exposes the case to public scrutiny through the media, and within a few days the individual in question is able to travel. Government officials then ask a judge to dismiss any lawsuits that were filed, saying the cases are now moot.

"The amount of people who experience tragic, life-altering travel delays is significant," said Abbas, who estimates he gets a call at least once a month from a Muslim American in dire straits because their travel has been restricted.

Government officials, of course, see it differently. They say they have a Traveler Redress Inquiry Program that lets people wrongly placed on the no-fly list, or the much broader terrorist watchlist, fix their circumstances.

More broadly, the government has argued in court that placing somebody on the no-fly list does not deprive them of any constitutional rights. Just because a person can't fly doesn't mean they can't travel, the government lawyers argue. They can always take a boat, for example.

"Neither Plaintiff nor any other American citizen has either a right to international travel or a right to travel by airplane," government lawyers wrote in their defense against a lawsuit by another of Abbas' clients. The teenager from Virginia had found himself stuck in Kuwait after suspicions about has travel to Somalia apparently landed him on the no-fly list.

Exactly how many people are on the government's lists is unclear. Some of the most recent estimates, from late 2009, state that about 400,000 individuals are on the "watchlist," which requires a "reasonable suspicion" that the person is known or suspected to be engaged in terrorist activities. A much smaller number — about 14,000 — is on the "selectee list," meaning they will likely have to undergo rigorous screening to travel. And officials estimated that 3,400 individuals, including roughly 170 U.S. residents, are on the no-fly list.

Calls and emails to the Department of Homeland Security and State Department's Bureau of Consular Affairs were not returned.

Michael Migliore was told by security officials last month that he is on the no-fly list after he tried to take a flight from Portland, Ore., to Italy following his college graduation. Migliore, a Muslim and a dual citizen of the U.S. and Italy, was planning a permanent move to Italy to live with his mother.

Migliore, 23, suspects he was placed on the no-fly list after he refused to talk to the FBI without a lawyer in November 2010, when the bureau was investigating an acquaintance charged in a plot to detonate bomb at a Christmas tree lighting ceremony.

"I feel that I did the right thing," Migliore said of his decision to exercise his rights when questioned by the FBI. "I didn't do anything wrong. ... It's very frustrating, not knowing what's going to happen, if I'm ever going to get off this list."

For now, he's waiting in Portland until he can get his name cleared for travel.

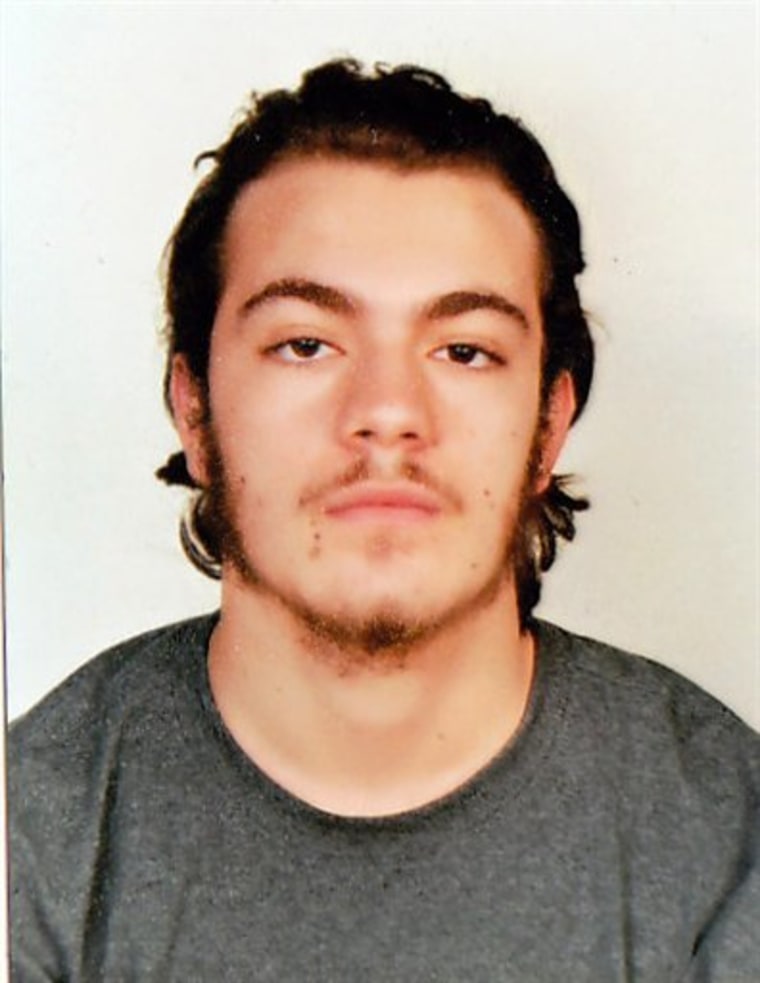

In another case, an 18 year-old U.S. citizen living in Jordan with his parents was bounced from an EgyptAir flight to New York. Amr Abulrub had planned to lead Ramadan prayers at a Connecticut mosque.

After a few days of confusion, Abulrub learned from airline officials that the U.S. government had instructed EgyptAir to cancel his ticket. U.S. embassy officials in Amman have subsequently told Abulrub he can travel under certain restrictions, including a requirement that his flight to the U.S. be booked on an American airline. But Abulrub is leery of traveling at all for fear that he won't be allowed to go back to Jordan.

Abulrub's father, Jalal Abulrub, suspects his son has come to the attention of U.S. authorities because of his own writings. Jalal is a Salafist scholar who has sometimes written provocative articles and antagonized Christian evangelists he believed were disrespectful to Muslims. While Jalal says his family is Salafist — generally considered a fundamentalist sect of Islam — he is quick to point out that he has a long history of writing in opposition to the ideology espoused by Osama bin laden and al-Qaida.

"I am not going to let this go," Jalal said, referring to his son's inability to travel. "We don't allow anyone to oppress us."