The state attorney general’s office sued to get back more than $100 million of former New York Stock Exchange chief Richard Grasso’s big pay package Monday, accusing him of bullying and manipulating his way to vast wealth.

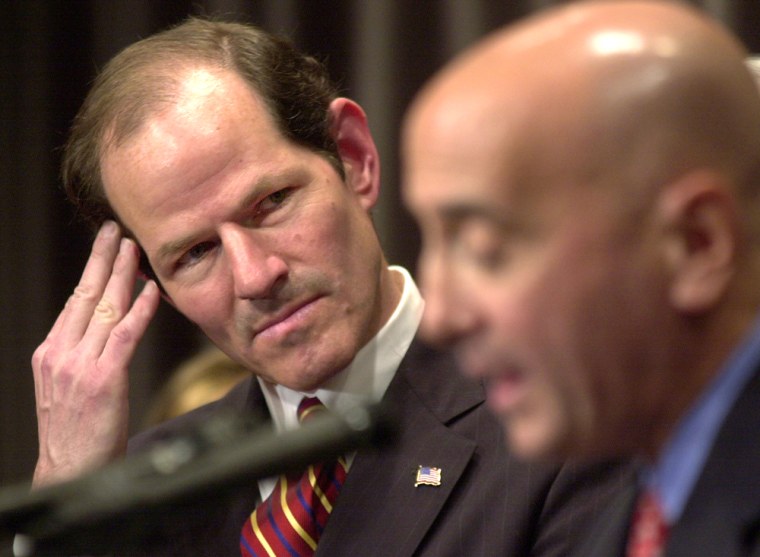

Attorney General Eliot Spitzer’s suit also named the exchange itself and a former NYSE board member as defendants following a four-month investigation into the controversial pay package. Grasso resigned as chairman and CEO last September amid intense criticism of his pay.

The suit asked that a State Supreme Court judge rescind the pay package and determine a reasonable level of compensation for Grasso. It names Grasso, the NYSE and Kenneth G. Langone, a former NYSE board member and ex-chairman of the exchange’s compensation committee.

“This case demonstrates everything that can go wrong in setting executive compensation,” Spitzer said. “The lack of proper information, the stifling of internal debate, the failure of board members to conduct proper inquiry and the unabashed pursuit of personal gain resulted in a wholly inappropriate and illegal compensation package.”

Spitzer maintained that Grasso, Langone and former NYSE human resources executive Frank Ashen misled compensation committee members by omitting retirement accounts and other aspects of Grasso’s pay package. The attorney general said he singled out Grasso and Langone because they allegedly actively misled the other board members, although the entire board could have been held responsible for approving the compensation.

“I drew the line based on those who misled and those who were misled,” Spitzer said.

Spitzer claimed the exchange’s directors were given inaccurate and misleading information before approving Grasso’s contract, and that certain deferred compensation plans and benefits were entirely left out of documents given board members.

He also cited testimony from an unidentified director and compensation committee member, whose firm answered to Grasso in exchange business, and who said he was asked to meet with Grasso in 2001 after privately expressing concern over the extent of his 2000 pay. Spitzer claimed Grasso cowed the director into approving the compensation package.

The attorney general also claimed Grasso’s payment formula was “inappropriately driven by a comparison with the salaries of top executives in the world’s largest corporations.”

“The compensation formula that generated huge payments for Grasso was flawed and under Grasso’s control,” the attorney general said, adding that even using those benchmarks, Grasso’s pay surpassed them by $80 million.

In a statement, Grasso said he looked forward to a “complete vindication in court and fully expect that my fellow NYSE directors and I will be adjudicated to have acted completely in accord with our fiduciary responsibilities and always in the best interests of the Exchange.”

Langone said in a statement, “These were honest, diligent and sound compensation decisions that were thoroughly researched and, most importantly, supported by 100 percent of the board. We all had access to that same information, beginning, middle and end and that’s why singling people out in this case is so obviously misguided.”

Langone, who headed the board’s compensation committee from 2000 to 2003, is considered a close friend and confidante of Grasso, and was instrumental in getting board approval for his compensation package. Spitzer was seeking $18 million from Langone, the amount of money the attorney general said Langone misled the board about.

Both men are directors of The Home Depot Inc., and Langone is a co-founder of the home improvement retailer. Grasso has opted not to run again for the company’s board at its annual meeting on Thursday.

Ray Pellecchia, an NYSE spokesman, said, “We are supportive of Attorney General Spitzer’s efforts in this matter. As a named party it would be inappropriate to comment further.”

Spitzer said he might seek injunctive relief against the exchange, which would effectively prohibit the NYSE from excessive compensation of its executives in the future. Any portion of Grasso’s compensation that Spitzer recovers, along with damages won from Langone, would be returned to the NYSE.

Spitzer also announced he had reached a settlement with Ashen and Mercer Human Resource Consulting, Inc., a consultancy that prepared a financial analysis of the pay package. Spitzer said Ashen and Mercer “admitted providing information to the board that was inaccurate and incomplete.”

In his statement to Spitzer’s investigators, Ashen admitted that internal worksheets used to calculate Grasso’s pay included a section detailing Grasso’s participation in a deferred payment plan for top executives. Those figures were not included in worksheets given to directors during their compensation deliberations, Ashen testified.

For its part, Mercer admitted that its report on Grasso’s final pay package, ultimately approved by the board in August 2003, did not adhere to the exchange’s typical methods for determining executive pay.

Under the settlement, Ashen, a top aide to Grasso, will return $1.3 million to the exchange, and Mercer will return the fees it charged the NYSE in 2003, totaling $440,275, Spitzer said.

Ashen and Mercer have already given Spitzer testimony about Grasso’s compensation and their role in providing misleading information to the board. Mercer had no immediate comment.

Bruce Yannett, Ashen’s attorney, said the former executive, who retired from the NYSE last year, was happy to put the matter behind him.

“Mr. Ashen recognizes in hindsight that certain mistakes were made, but at no time did he intentionally provide inaccurate or incomplete information to the Board of Directors,” Yannett said in a statement.

Mercer said in a statement it settled the case “solely to put this matter behind us and to avoid the cost and distraction of protracted negotiation.” The company said it did not make recommendations regarding the structure or amount of payment of Grasso’s compensation package, and that it reported solely to Ashen.

Grasso resigned as chairman and CEO as the controversy surrounding his pay reached its peak. He has received $139 million of his compensation package, and recently told Newsweek he would forgo the rest if the exchange would apologize for tarnishing his name.

The NYSE, for its part, has already asserted that Grasso should return the bulk of his compensation. In February, interim NYSE chairman John Reed wrote to Grasso’s lawyer, demanding the return of $120 million; Grasso refused.

Spitzer filed his suit under New York’s Not-for-Profit Corporation Law. His investigation is separate from a probe of Grasso’s compensation by the Securities and Exchange Commission, which is considering whether there was a violation of federal securities laws or the NYSE’s bylaws.

“The SEC will make the difference,” said Ed Murphy, civil litigator and a senior partner at Beirne Maynard & Parsons in Houston. “If the SEC is out of the picture, even though Grasso may unsympathetic to a lot of juries, there will be a strong defense. If the SEC is in the picture, then there will be a settlement and it’ll have to be a three-way settlement.”

Matt Well, an SEC spokesman, said Monday, “At this point we don’t have a timeline” for the commission’s investigation.