The nation’s three biggest states, California, Texas and New York, have a total of more than 38 million registered voters and huge clout in the Electoral College, with nearly half of the number of electoral votes needed to win the White House.

Yet down the home stretch of this fall’s presidential campaign, the chances of John Kerry or George Bush campaigning in front of any of the 38 million voters in those three states is close to nil.

One quirk of presidential election dynamics since 1988 is that nearly all of the most populous states are uncompetitive, the virtually uncontested turf of either the Democratic or Republican candidate. The Democrats dominate in California and New York and the Republicans "own" Texas.

It was not always so clear cut: Jimmy Carter carried Texas in 1976, something no Democrat has done since then. And George Bush carried California in 1988, a feat no Republican has pulled off since.

Gore's margins

In 2000, Al Gore carried California by nearly 1.3 million votes, swept New York by 1.7 million, and took Illinois by more than 500,000.

Gore’s massive vote margin in those three states was of no value to him since, in most cases, if a candidate wins a state by the vote of even one person he gets all of that state’s electoral votes.

While it may be personally gratifying for a Democrat presidential candidate to be intensely popular in California, or for a Republican to have overwhelming support in Texas, in each case he would be better off trading intensity for more diffusion of his loyal supporters across state lines.

If only a tiny fraction — less than 2 percent — of those 1.3 million “surplus” California Gore voters had moved next door to Nevada and voted there in 2000, it would have made all the difference.

By tipping Nevada’s four electoral votes to Gore, they would have given him precisely the total of 270 he needed to become president.

Intensity, as manifested by a lopsided margin in a big state, simply does not pay off in presidential elections.

Intensity within a state

That rule does not apply in the winner-take-all battle within a state for its electoral votes.

In those contests, intensity in one area can be decisive. In the battle to win Pennsylvania, for example, Bill Clinton got 77 percent of the votes in the city of Philadelphia in 1996. In small Tioga County, a proxy for other rural Pennsylvania counties, he got 34 percent.

The pattern grew even stronger in 2000: Gore won 80 percent of the vote in Philadelphia, offsetting his performance in rural counties such as Tioga where he won only 31 percent.

Democratic domination of the big cites stretches back nearly 70 years. The last Republican presidential candidate to carry the city of Philadelphia was Herbert Hoover in 1932.

In 2000, Gore bested Clinton’s Philadelphia performance by winning 36,000 more votes in the city than Clinton had in 1996. Philadelphians were intensely pro-Gore and that helped put the state’s 23 electoral votes in his column.

In the struggle for each state’s electoral votes, Democrats need intensity — massive votes and big margins — in cities and suburbs to offset their low votes in rural areas.

Of the 10 most populous states, four (California, New York, Illinois and New Jersey) are virtually certain or very likely to go for Kerry on Nov. 2, while two others, Michigan and Pennsylvania, lean decidedly Democratic.

With six of the 10 most populous states solidly Democratic or leaning Democratic, only Texas and Georgia are virtual locks for Bush among the 10 biggest states.

Only two big toss-ups

What’s left? Only two genuine tossup states among the Big 10: Ohio and Florida.

It happens to be the case that some relatively small states are also places where margins were excruciatingly close in the 2000 Bush vs. Gore contest: for example, New Mexico, Oregon, Iowa and New Hampshire, where the victor’s margin ranged from a nearly imperceptible 0.06 of a percentage point (366 votes) in New Mexico to 1.27 percentage points in New Hampshire.

A candidate can win the White House — and Bush did so — by winning a lot of small and medium states.

The Electoral College system gives a bonus to the small states: No matter how few people a state has, it gets two "extra" electoral votes, equivalent to its two senators. Thus the electoral vote is not exactly proportional to the state's population.

Wyoming, with a voter turnout of only 213,000 in 2000, got three electoral votes.

In California nearly 11 million people turned out to vote in 2000, more than 50 times as many as in Wyoming. But California (and Gore) got 54 electoral votes, only 18 times as many as Wyoming got.

The big states, where Gore got those lavish vote margins, are underweighted in the Electoral College and that tends to cost the Democrats.

Bush wins the small ones

Of the states with four million or fewer registered voters, Bush won 26 (with a total of 171 electoral votes) and Gore won 14 (with 89 electoral votes).

Of course, small state populations and close presidential elections don’t always correlate: You can’t find a more true-blue Democratic state than tiny Rhode Island, nor a more Republican state than high, wide and nearly empty Wyoming.

But their electoral votes, three for Wyoming and four for Rhode Island, give them minimal Electoral College impact and it’s not likely you’ll see Bush or Kerry tarrying in Cheyenne, Wyo., or Newport, R.I., this year.

Rather, these small states simply blend in to each party’s regional bastions: For the Democrats, Rhode Island is part of the Northeast fortress of Massachusetts, Vermont, Connecticut, New York, New Jersey and Pennsylvania.

For the Republicans, Wyoming is a part of their Western stronghold, an Upper Plains and Rocky Mountains base stretching from the Dakotas west to Idaho and south to Utah and Arizona.

The phenomenon of partisan big states combined with small to medium wavering states such as Wisconsin and New Hampshire creates the situation for a candidate to win the popular vote but lose the electoral vote, as Gore did four years ago.

Giuliani and Schwarzenegger

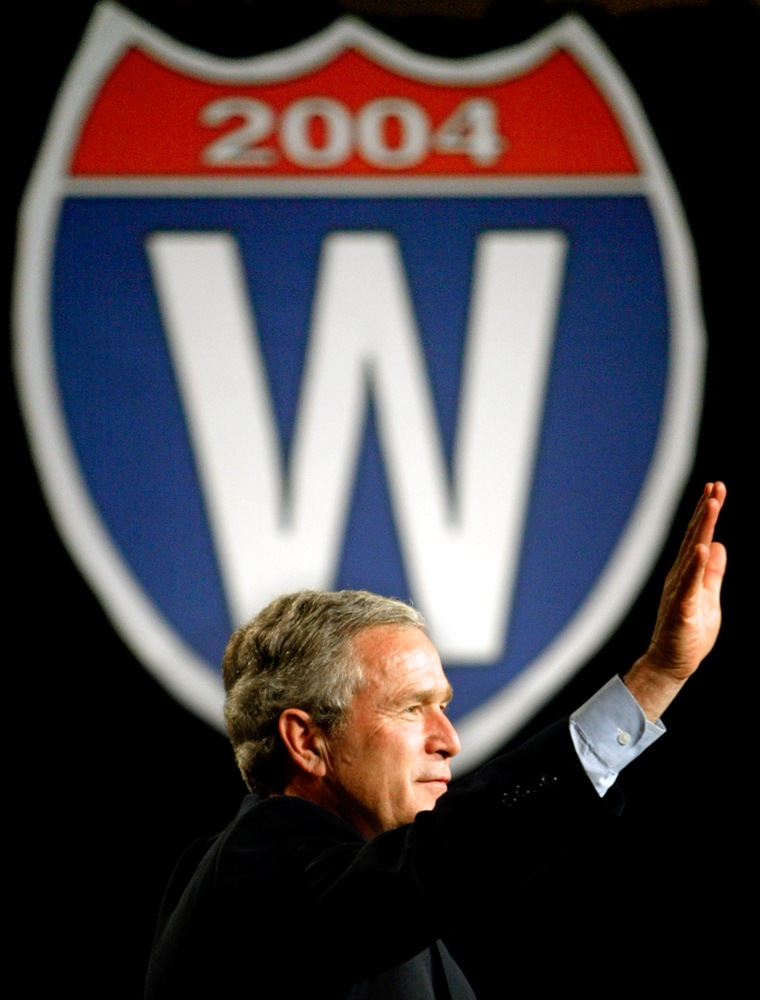

No doubt Republicans would respond to all this by saying they have not conceded New York or California to Kerry, arguing that “after all, we’re holding our national convention this summer in New York. And two of most our popular party personalities are the current governor of California and the former mayor of New York City.”

Former Mayor Rudolph Giuliani will speak on the Republican National Convention’s opening night and California Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger on the second night.

But Schwarzenegger and Giuliani, who stand out by their differences with most Republicans on issues such as abortion and gay rights, are being put on display to give a more centrist face to the party as Bush makes a play for undecided voters.

What makes Schwarzenegger and Giuliani successful in such heavily Democratic places as New York City and California is what makes them atypical Republicans.