The Grand Ayatollah Ali Sistani, the most revered Shiite leader in Iraq, seems through the prism of the Western media to be an elusive character. He has not met with coalition leaders directly, and he doesn't speak to reporters. His views on current affairs are known through statements made by those who surround him, which makes the ayatollah appear a remote, oracular, figure. Although he has avoided jumping directly into the political process, election results announced this week make his Shiite supporters the dominant force in the new government, and Sistani has proved in the past that he can muster tens of thousands of protesters to influence the course of the new Iraq. His impact on U.S. efforts to remake Iraq has been enormous. And yet he remains in many ways an enigma, an unseen hand and a powerful force guiding the country who knows where.

His views on religion, however, are perfectly clear and surprisingly available even to people who don't speak or read Arabic or the Iranian-born ayatollah's native Persian. Some of his works, including "Islamic Laws: According to the fatwa of Ayatullah al Uzama Syed Ali al-Husaini seestani," an English translation of his religious edicts, are available from a publisher based in Tehran. And while his works aren't easy to find in U.S. bookstores, Sistani's writings can be found, and searched electronically, online, at www.sistani.org.

They reveal a mind that works with Aristotelian precision, an intellect that thinks through categories, definitions and the fine art of splitting differences. But they also reveal a religious world that would be, even to the most devout Americans, invasive into the details of daily life.

For example, fatwa 2648 reads: "It is unworthy to drink too much water; to drink water after eating fatty food; and to drink water while standing during the night. It is also unworthy to drink water with one's left hand; to drink from the side of a container which is cracked or chipped off, or from the side of its handle."

Traditional edicts

Sistani's edicts are squarely within the Shiite tradition, and he's considered by many observers a moderate in most things. Rulings on his Web site, for instance, say that it is considered permissible to have a face-lift and to listen to music (so long as the music isn't frivolous or "fit for diversion and play"). Speaking to one's fiance on the telephone is also permissible, if the conversation is "free of provocative words and if there is no fear of falling in sin." And while he works within the tradition of Islamic jurisprudence, his references can be surprisingly wide. Citations from Alfred Hitchcock and Will Durant are marshaled in a set of rulings about the general attractiveness of modest women.

As a marja — a scholar of such immense authority that not only can he can give new interpretations of Islamic law, but serves as a source of emulation to the faithful — Sistani responds regularly to questions from fellow Shiites, who are free to follow his advice, or the advice of any other qualified religious scholars. It's clear from Sistani's introductions to his various collections of rulings that he senses the weight of his responsibility, of taking onto his own shoulders the responsibility for deciding the regulation of religious life. Throughout his writings, there are basic principles: He expects scrupulous honesty and integrity from the faithful; there is to be no gaming the system and no use of the letter of the law to avoid the spirit of it; and he's not a fundamentalist, but rather he looks to the larger intent rather than the literal meaning of the scriptural passages he cites.

In his advice to Muslims living in non-Muslim lands, he emphasizes respect for other religious and cultural traditions, along with a strong emphasis on maintaining Muslim values. In the fatwas he's issued during the invasion and occupation of Iraq, he has been a moderating influence, discouraging violence and retribution, and encouraging participation in the democratic process.

Sistani was born in 1929 near Masshad, and began studying the Koran at age 5. In 1952, after studies in the Iranian religious center of Qom, he moved to Najaf, in Iraq, where he studied with the Grand Ayatollah Abul-Qassim al-Khu'i. In 1992, after the death of Khu'i, he was selected to succeed his teacher as the head of Najaf's network of religious schools. Sistani has been in ill health recently and traveled to London last August for treatment.

Considered ‘very moderate’

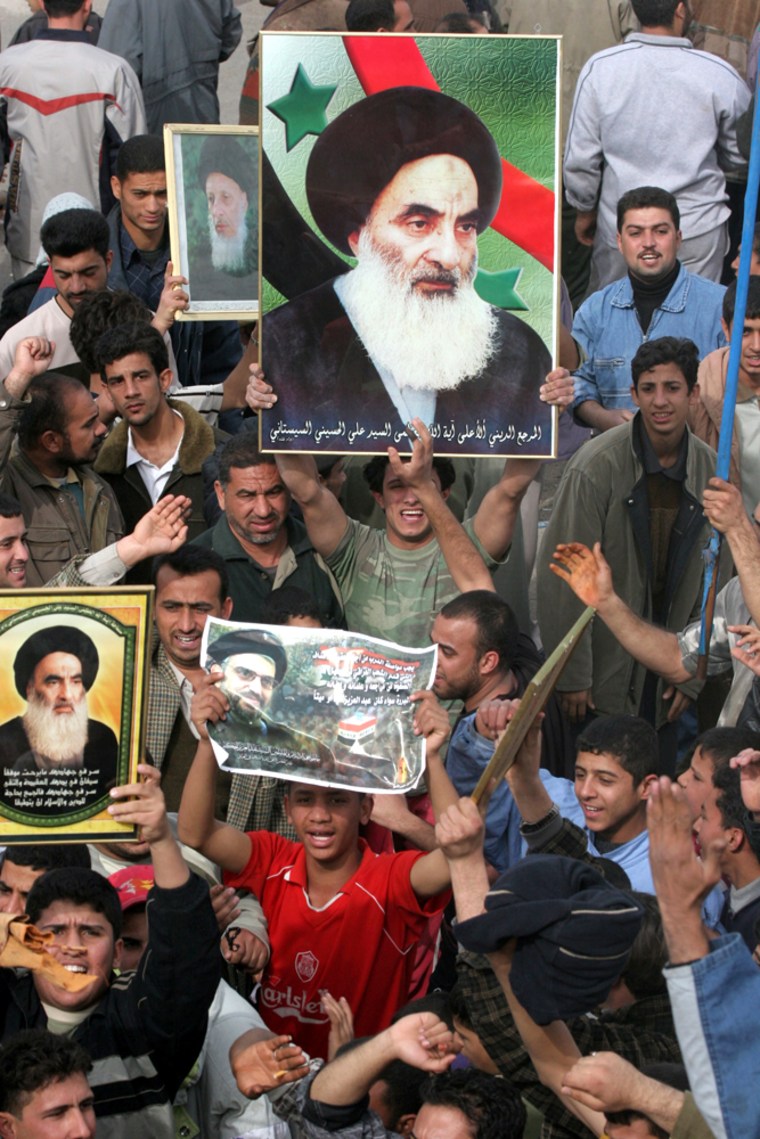

In January 2004, he insisted that elections for a transitional government to write a new constitution should be direct and democratic. This led him into conflict with American leaders, who preferred a system of regional caucuses. His supporters protested the American plan en masse, and the United States backed down.

"In every generation you have some mujtahids who are more strict, and some less strict," says Seyyed Hossein Nasr, professor of Islamic studies at George Washington University, using another term for scholars who are qualified to give new opinions on the basis of existing religious law. Among his peers, says Nasr, Sistani "is very moderate."

Moderate is a relative term, especially within a tradition that is extremely thorough in the way it parses the right and wrong of daily life. Sistani, for instance, often decides it is permissible to do things that, within other religious contexts, would never have been questionable in the first place.

Fatwa 2638, for example, reassures the reader that "there is no objection in swallowing the food which comes out from between the teeth at the time of tooth picking."

Nasr, and other scholars of Islam, point out that this approach to religious law is similar to that of Orthodox Judaism. The hundreds of rulings that deal with prayer, bodily functions, marriage contracts and alms are part of an ancient tradition shared by several faiths.

"Those are practical matters, not his preoccupation," says Nasr. "It is a question of ritual purity, in religions like Islam, Judaism and Hinduism."

Since a death sentence was called down on the writer Salman Rushdie by the Ayatollah Khomeini, the term "fatwa" has been linked in the West with a medieval notion of retribution. But the vast majority of fatwas have to do with details of bathing, menstruation, sex and business. And though they reflect the dictates of ancient religious ideas, they are part of a dynamic tradition in which religion is constantly adapting to new challenges and threats. One of the liveliest sources of new religious thought is on the Internet, where fatwas are available online for Muslims grappling with a changing world.

Sistani's thought builds on and elaborates the rulings of his revered predecessor, Khu'i. Taken individually, out of context, rulings such as those offered by Sistani can seem disturbingly preoccupied with moral minutiae, often raising more questions than they seem to answer.

If, for example, a "person commits sodomy with a boy, the mother, sister and daughter of the boy become haraam for him," begins one ruling. The particulars of the fatwa deal only with the status of women related to a sodomized boy, who would seem to be the more pressing object of religious concern. But numerous other rulings deal with the impermissibility of same-sex relations. The seeming narrow focus of religious rulings is an inevitable byproduct of their being essentially refinements of first principles. For the poetry of those first principles, for the soaring statements of right and wrong and decency that Christians find in the Sermon on the Mount, one has to look to the books -- the Koran and the Hadith -- upon which Sistani's thought are based.

Interested in political involvement?

U.S. political leaders, including Vice President Cheney and Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld, have been eager to reassure Americans that, despite Sistani's immense influence, the ayatollah has shown no interest in stepping directly into Iraq's political fray. They have contrasted Sistani's religious focus with the overt call to political arms in the writings of Khomeini.

They are right about the political differences between Sistani and Khomeini. Reading the works of Khomeini after the works of Sistani is a bit like dipping into Plato's "Republic" after spending time with Aquinas: Khomeini had a sweeping, revolutionary view of the state as a source of virtue, markedly different from Sistani's limited view of the state as an institution run by the best men one can find.

Some of Khomeini's writing even engages directly with the mainstream, legalist tradition represented by Sistani, in a way that suggests that Khomeini was self-conscious about the challenge of forging modern political entities out of the ancient traditions of Islamic law.

"But the foreigners have whispered to the hearts of people, especially the educated among them: Islam possesses nothing," Khomeini wrote in "Islamic Government," encouraging readers not to succumb to Western parodies of Islamic religious strictures. It is self-defeating to think of Islam as "nothing but a bunch of rules on menstruation and childbirth."

Strong conservative strain

But while Sistani's thought is far from the radical Shiite leaders who led the Iranian revolution, it isn't accurate to say it's apolitical. While he himself leaves politics to politicians, Sistani's understanding of religious law leaves very little of the world beyond the scrutiny of religious leaders. In fact, it is difficult to carve out realms of the "private" and "political" that have much meaning. In the interest of maintaining things such as modesty and ritual cleanliness, there is a paradox: Women's bodies are subject to particularly close observation, so much so that that many of Sistani's rulings can't be quoted in a family newspaper.

While American leaders emphasize that Sistani isn't like the clerics of Iran, others point out that the Shiite tradition leaves Sistani little wiggle room on fundamental topics, including women's rights.

"It is important to keep in mind that there are certain issues in the Shiite community about which no ayatollah, however progressive, can afford to deviate in his deliberations and final ruling," Abdulaziz A. Sachedina writes in an e-mail from Iran. A professor of Islamic studies at the University of Virginia, Sachedina met with Sistani several times in the 1990s, and on one occasion Sistani criticized his writings and issued a ruling against Sachedina's public comments on matters of faith. Sachedina was undaunted and says he carries "no grudge" against Sistani. Nonetheless, Sachedina's inside view of Sistani and Sistani's organization lead him to consider the ayatollah more conservative than do other observers.

Sistani's views on women "are restrictive and in his personal communication to me in 1998 he made it very clear that he abides by the age-old opinions regarding women's inequality with men, and that he regards their testimony, as extrapolated from the Qu'ran, half of a man's testimony in value," the scholar writes.

Sachedina also believes that the aging Sistani is strongly influenced by his son and sons-in-law, who run his large and wealthy international organization.

"My overall assessment of [Sistani] is that he is conservative and certainly [a] political opportunist who would readily change his opinion to get the support of a specific group for political ends," Sachedina writes.

It is unlikely, given Sistani's background, his writings, and his embodiment of a conservative religious tradition, that he will emerge as an ideal cultural leader by U.S. standards. In a society ruled by religious law, in which every detail of life can be subjected to a ruling by a religious scholar, the citizen has a much more direct and dependent relationship on authority than in secular democracies. Elections may decide who runs the government, but culturally, a tradition of dependence on religious authority may make it difficult to establish the kinds of rights and freedoms taken for granted by citizens of democracies that draw a stronger line between church and state. None of this precludes political democracy, but a reading of Sistani's writings suggests there may be a lot less room for personal freedom than American leaders, who have downplayed the consequences of an Iraq ruled by sharia law, acknowledge.