The suicide rates among veterans are astounding: 22 die by suicide daily. And behind the scenes are the spouses and family members who often get little support in their own battle to care for their loved ones.

“Family members can too often become the invisible folks, the forgotten ones,” Keith Hotle, chief program officer of Stop Soldier Suicide, told Know Your Value. “The same way that it would be if someone were chronically ill, it becomes the focus of your world. Everything else, including you, takes a back seat.”

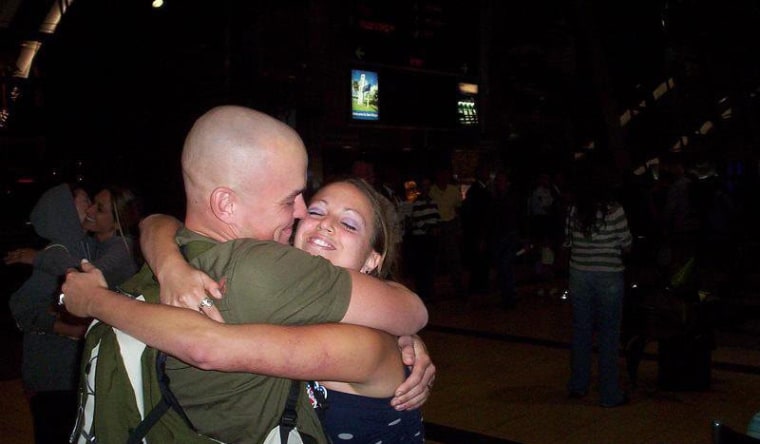

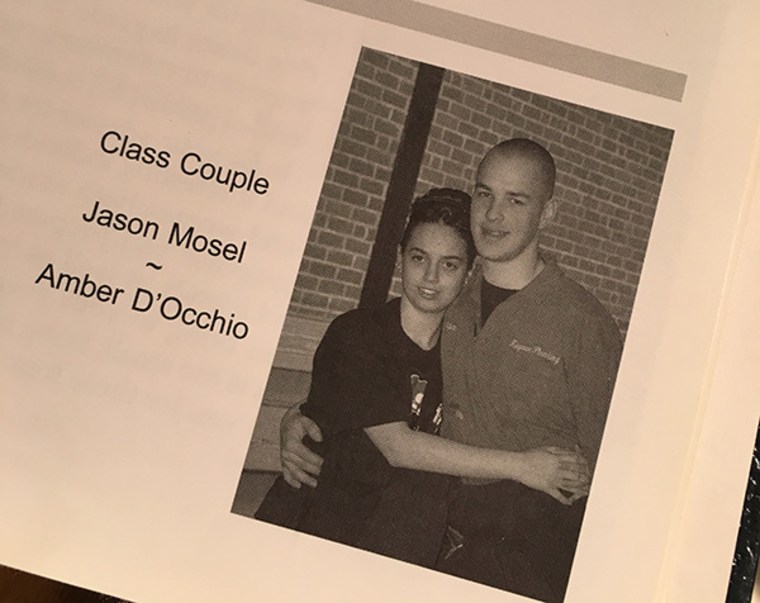

That’s how it felt for Amber Mosel, wife of retired Marine Sgt. Jason Mosel. The high school sweethearts have been together for more than half of their lives, and their relationship has survived major hurdles: Jason’s three deployments, threats of divorce and a suicide attempt.

“I learned very quickly that there’s no crying on the phone when they call you on that sat [satellite] phone from Iraq,” Amber, 34, said. “I decided I had to be mentally stronger in that situation. And that’s just the attitude I applied to everything over the years.”

Sgt. Mosel is now mentally and physically healthy, and he’s using his story to help others: On March 22 he will attempt to break the Guinness World Record for the most chest-to-ground burpees in 12 hours. He’s live-streaming the overnight event to raise awareness about veteran suicide.

But to get to this point, Jason and Amber had to fight an uphill battle.

‘Things started to change’

After graduating high school in Connecticut in 2003, Jason headed to South Carolina for boot camp and then to Camp Lejeune for infantry training.

“During and after boot camp, he was an absolute sweetheart, writing me all these letters including one where he asked me to marry him,” Amber said. “But when he went to infantry training, things started to change.”

Jason was “a little more distant” in his letters and phone calls from Camp Lejeune, but Amber told herself it was simply because he was settling into a new environment. To try and understand Jason’s experience Amber frequently watched “Full Metal Jacket,” Stanley Kubrick’s Vietnam War movie, while Jason was at boot camp.

After basic training, Jason deployed to Iraq in February 2004. The seven-month duty was particularly hard. A total of 34 Marines in Jason's battalion were killed and he saw one especially close friend die.

Amber spent a lot of time talking with her family during this period, and she focused on being stoic and strong for Jason. She also poured herself into writing pages-long letters daily.

“Writing to him about what I did every hour of the day is what saved me,” Amber said. “It made me feel like he wasn’t disconnected. Life is carrying on here and you’re still with me because I’m sharing this daily routine.”

But Jason’s responses were erratic. For example, he’d tell Amber one day that she should leave him and the next day that they should get married right away. They did end up tying the knot in October 2003 during a two-week leave for Jason.

Still, Amber knew things weren’t right. When Jason first landed back home in California, he immediately headed to a bar and got drunk. The situation declined from there.

“We were walking through a parking lot and he refused to hold hands because he was used to carrying a rifle,” Amber said. “His eyes were dark the whole time, like he still thought he was in Iraq with the roadside bombs.”

Amber had no idea what to do. “No one briefed me on what to expect, so I didn’t know if this was ‘normal,’” she said. “But he was on edge constantly. The only time he wasn’t was when he was drunk.”

Jason mentioned he was having trouble sleeping but didn’t want to talk about his feelings with Amber. Then came a second deployment, this time to Okinawa, Japan, in spring 2005. That’s when things got worse.

Suicide attempt

By the time he got to Okinawa, Jason recognized he had serious depression and saw a mental health professional who prescribed “a cocktail of pills” that numbed him but didn’t make him feel better.

Amber tried to be “a light for him,” but Jason constantly tried to break off the relationship. When discussions about divorce became more frequent, Amber packed up her stuff in their San Diego County home and moved back near her family in Connecticut.

But the two stayed in close touch, and one day Jason’s AOL Instant Messenger messages were alarming to Amber. They were short, dark and cryptic — and then he made a comment about “ending it all” before signing off.

A frantic Amber, with no phone number to call Jason or anyone else with him, finally got in touch online with another member of Jason’s battalion. She begged the friend to check on Jason, and they found him unconscious after attempting suicide with pills and alcohol. He was only 19 years old.

Jason was rushed to the hospital, brought to a mental health facility and placed in rehabilitation programs. He also left Okinawa a bit early and headed back to his base in California.

At home in Connecticut, Amber “was devastated and confused,” she said. “I wondered what I could have done.”

That’s a typical reaction from family members, said Hotle of Stop Soldier Suicide. “It’s virtually impossible to support someone through this alone at all, and it’s absolutely impossible to do it for an extended period. The harsh reality is that you’re dealing with someone who may experience this forever, and you can’t handle that alone.”

Road to healing

Jason did get help in California, working with therapists and attending Alcoholics Anonymous meetings. He finally begged Amber to come out for their wedding anniversary — and stay for good. “I got my one-way ticket, because I’m a strong believer in trying everything you have,” she said.

Things felt a little bit awkward at first, as if they were in the early days of dating. But their relationship flourished, and Jason deployed to Iraq again from winter 2006 to spring 2007 for his final tour of duty before being honorably discharged from the Marines.

Amber and Jason subsequently packed a U-Haul and moved to Corinth, Vermont, to enjoy life in a more rural setting. They still live there now, where Jason works as a technical operations supervisor for Comcast.

The road to strong mental health hasn’t been linear, with Jason falling into patterns of heavy drinking in the first several years of their time in Vermont. But with the help of a therapist, dedication to working out and the support of endurance-race communities like Tough Mudder and Spartan Race, Jason has been doing well over the past few years.

“Looking back it’s hard to say how we got through,” Amber said. “I was angry early on, I was frustrated, I wasn’t perfect. But through it all I tried to be that ray of sunshine in his life because that’s what he needed.”

Amber leaned on family and her own internal strength to get herself and her husband through. But she does “wish there were more resources to check on [veterans] mentally after they come back, and for family members too,” Amber said. “If you suspect anything is wrong as a wife, you don’t really have someone to talk to.”

Groups like Stop Soldier Suicide aim to fill that gap, working in part to help military members and their families “navigate the complex systems within Veterans Affairs, Department of Defense, etc.,” Hotle said. “There’s a reluctance to seek help or admit weakness, and it doesn’t help to have a bunch of bureaucracy to cut through.” Additional resource groups include Healing Household 6, a nonprofit that provides assistance to military caregivers during emergency situations.

About 25 percent of Stop Soldier Suicide’s clients are family members, and 10 percent are spouses specifically.

“Our message is one of hope,” Hotle said. “We want people to know there is support out there, and there are a lot of people like you who are going through this and have gone through it. It’s never hopeless.”

Self-care and warning signs

For spouses and family members struggling to support their loved one, Hotle recommends taking three major steps: Communicate with your spouse as much as possible about what they’re feeling; create a support system of friends, family, mental health professionals and others to help; and build self-care, even if it’s just a few moments to yourself, into the daily routine to avoid burnout.

The suicide warning signs for military members are the same as those for civilians, Hotle said. The National Alliance on Mental Illness lists common symptoms on its site, and many of them — such as changes in sleeping habits and avoiding friends — are related to “significant mood shifts and major behavioral changes,” Hotle noted.

“It’s going to be different for every individual, and it might be something a spouse notices but someone like a co-worker wouldn’t,” he added. “For me, a quiet guy, coming home and yelling would be odd. But it might be normal for the guy down the road.”

For military in particular, Hotle also recommended thinking about access to firearms. "A friend of mine is bipolar and when he felt on the verge he gave his wife the keys to the gun cabinet," Hotle said. "It’s a smart preventative measure to reduce risk.”

For the Mosels, life at the Vermont cabin and immersion in intense physical activity have been the key to a brighter future. They’re always vigilant about keeping each other focused, upbeat and motivated. They take turns writing quotes in a journal to set the tone for the day each morning.

For example, a recent quote was from Kathrine Switzer, the first woman to run the Boston Marathon with a bib number, and it’s one of Amber’s favorites: ”Life is for experiencing, not participating.”