If it ever feels like you're wasting your life in traffic, that's not far off. The average American driver spends 42 hours a year in jams (about 9 percent of their total drive time), according to the traffic information company INRIX. In heavily congested cities like Los Angeles and New York City, that figure more than doubles.

Recently, Tesla CEO Elon Musk announced his new venture, the Boring Company, which aims to solve our ever-increasing traffic problems by creating a complex network of subterranean tunnels for cars. The project will no-doubt be a marvel of engineering, but experts suggest that simpler alternatives may be preferable solutions to our traffic woes.

Related: Elon Musk's Answer to LA Traffic Looks Like a Lot of Fun

In Musk's vision, vehicles enter a citywide tunnel system on single-car electric “sleds” that lower cars from street level down into the buried network and then take off, carrying their loads at speeds of up to 125 mph. The project will start in LA but may spread to other cities if it's successful. By Musk's estimation, these sleds — which can automatically weave between various tunnels depending on the destination, where they're then lifted back to the surface — would take just five minutes to travel south from LA's Westwood Village to LAX airport, a 10-mile trip that would normally take 30 to 60 minutes in traffic.

Current designs suggest a single mile of the tunnel could cost $1 billion. That tremendous price tag aside, the endeavor may not work as Musk hopes.

The tunnels are the equivalent of adding extra lanes to roadways and would have the same results, says Hesham Rakha, director of the Center for Sustainable Mobility at the Virginia Tech Transportation Institute. That is, adding supply to your network inevitably creates so-called induced demand, in which drivers change their behaviors to make use of the increased network capacity. They'll take trips they wouldn't have otherwise taken, along routes they think are most favorable (in this case the tunnels). And unless there are large terminals or staging areas at the tunnel’s entry and exit points, you'd ultimately see a long line of cars awaiting their sleds and gridlock on streets where vehicles leave the underground network.

So, while the Boring Company may alleviate traffic slightly, it's not a long-term solution, Rakha says. "People always try to minimize their own travel time but don't look at maximizing the utility of the entire system."

That's not to say traffic congestion is an unsolvable issue. Rakha and other experts are proposing various alternatives — in particular, connected autonomous cars, efficient public transportation, and pricing methods like road tolls — that can help put an end to traffic. The challenge is figuring out what works best for a given city and how to implement these seemingly straightforward ideas.

Smart Cars for Dumb Drivers

Ending traffic requires understanding what causes it in the first place.

Between vehicle accidents and lane closures, there are numerous reasons why traffic may build up on roads. But sometimes you find yourself in stop-and-go traffic that has no apparent cause; and then suddenly, after reaching an arbitrary point, the congestion eases up.

Nearly a decade ago, Gábor Orosz, a mechanical engineer at the University of Michigan, found that these spontaneous jams are the result of "little ripples" of slowdowns that are amplified as they propagate backward along a chain of vehicles. There are two main factors involved, he says: Drivers have a slow reaction time of about 0.5 to 1.5 seconds and they're only reacting to the vehicle directly in front of them.

Related: Self-Driving Cars Will Turn Intersections Into High-Speed Ballet

In an ideal world, drivers would be nimble and attentive and be able to keep an eye on several cars ahead of them, allowing the driver to react to various scenarios with a light tap on their brakes. But instead, drivers often react late and must brake quickly to avoid accidents. This rapid deceleration forces the driver immediately behind them to slow down further, creating a cascading effect that creates a standstill several miles back.

"When we have between approximately 20 to 40 cars per kilometer, we can get either a jam or get free-flow traffic," Orosz says. "And if we have higher densities [of cars], we almost always have jams because humans are not able to maintain uniform flow." The solution to this problem, Orosz suggests, is to remove human drivers from the equation.

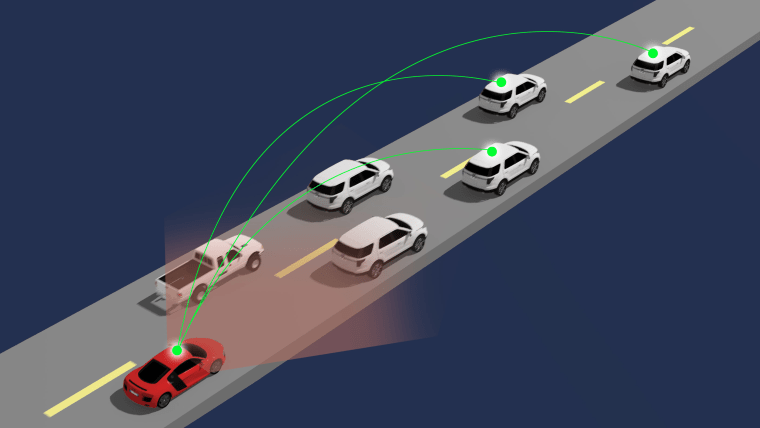

Today, almost all car companies (and tech giants like Google) are working on self-driving car projects, Orosz says. These vehicles sense the world and other cars through a combination of cameras, radar, sonar, and lidar (remote sensing with lasers). The cars can react more quickly to situations than human drivers, helping improve traffic conditions. But they’re still only reacting to vehicles in their immediate vicinity, Orosz says, adding that dedicated short-range communication (DSRC) technology fixes this limitation by allowing cars to "see" beyond their direct line of sight.

When equipped with DSRC radios, autonomous cars automatically broadcast their location, direction, and speed to one another over a specially allocated 5.9 GHz radio frequency band. When connected vehicles know what other DSRC-equipped vehicles are doing, they can travel in unison as highly efficient and dense vehicle "platoons." The U.S. Department of Transportation is seeking to require all new cars to have vehicle-to-vehicle communication starting around 2020 (only a handful of cars today have such technology built-in, none of which are autonomous).

Though DSRC is a relatively cheap technology, fully autonomous cars probably won't be, so eliminating jams with these cars alone may not be feasible. However, reducing traffic jams doesn't require all cars on the road to be connected autonomous vehicles. "Making a few percent of these to be connected autonomous vehicles can result in a huge improvement in traffic conditions," Orosz says.

Taking Cars Off the Road

Connected autonomous vehicles are, like the Boring Company, a technological solution. But traffic congestion is a geometric problem and "technology never changes geometry," says public transit planning expert Jarrett Walker, author of "Human Transit."

"A city is a place where people are close together and there isn't enough space per person," Walker says. "A car is an inefficient use of that space."

The solution: fewer cars on the road. But how do you go about removing them?

To solve traffic congestion, you need to understand that road space is governed by supply and demand, Walker explains. Simply put, reduce the demand for road use and you'll reduce traffic. Implementing road pricing, which can take various forms, is a great way to reduce demand for road use, Walker says. Tolls, for instance, are well-known tools to discourage people from driving on certain high-use roads, especially if the tolls are higher during peak hours.

But there are many ways to discourage driving. In cities like London, congested downtown areas could have fees for driving and for using select public parking spaces. Employees could be given cash incentives to give up their parking spots, encouraging them to take public transit or to carpool rather than drive to work alone. Fuel taxes could be increased, and drivers could be taxed based on the number of miles they drive in a year.

Some cities, including Paris and Beijing, have taken an extreme approach that bans cars with even- or odd-numbered license plates from driving in city limits during specific days or times.

"Road pricing is a free-market approach that's not particularly ideological," Walker says. "This is one of those issues where practically every transportation professional knows this is the answer, and the only reason we keep looking elsewhere is that, politically, we don't like it."

A Holistic Approach

Virginia Tech's Rakha agrees that reducing demand is a key component to solving traffic, but he says that increasing supply is also important.

"You have to look at the system as a whole," he says, adding that focusing on one side of the equation will lead to a never-ending cycle of network adjustments and driver responses. "It's a chess game: When I make a move, my opponent will make a counter-move. You have to take that into account when you are doing some adjustment to your network, and think about the counter-move that drivers will make."

"People always try to minimize their own travel time but don't look at maximizing the utility of the entire system."

Connected autonomous vehicles could be one tool used to increase supply, Rahka says. And for people who refrain from driving because of road pricing, efficient and reliable public transportation, such as trains, subways, and buses, is vital to making the system work. Walker doesn't advocate a specific public transportation technology but says the mode should be "protected" from traffic congestion — buses that drive on the same roads as cars are not ideal because they're still contributing to road use.

The best public transportation technology also depends on the layout of the city. European cities are often condensed and centrally focused, so subways that can take many passengers from their homes to downtown areas work well.

In many U.S. cities, however, people in the suburbs don't always live near transportation hubs. One solution for this problem is the "last mile," or programs that bring people between their homes and transportation hubs, such as bicycle-sharing programs and ride-sharing vans.

Related: Driving on the Roads of the Future Will Be a Real Trip

Overall, there are numerous tools that can help reduce traffic by reducing demand or increasing supply, but ending traffic congestion altogether is not so straight-forward. Whether city officials add tunnels underground, increase the number of smart cars on the road, or discourage people from driving, they need to model the system and simulate how different strategies will potentially affect traffic congestion.

"Rather than trying to fix one bottleneck after another, you need to first evaluate different alternatives and try to capture how travelers are going to react before you implement them in the field," Rakha says. "Of course, any model has its flaws and there will be approximations and assumptions, but that's at least better than just building blindly."