Fake blood vessels are starting to get real.

New research shows that “bioengineered” blood vessels are able to incorporate living cells after being implanted in the human body, becoming blood-carrying, self-healing tubes that function less as substitutes for human blood vessels and more like the real thing.

The so-called human acellular vessels (HAVs) are experimental devices and aren’t yet ready for widespread use. But if the new research is supported by subsequent studies, HAVs might someday be used to treat medical problems ranging from cardiovascular disease to gunshot wounds.

“This is the wave of the future,” said Lola Eniola-Adefeso, a University of Michigan biomedical engineering professor who was not involved in the research, which was described March 27 in the journal Science Translational Medicine.

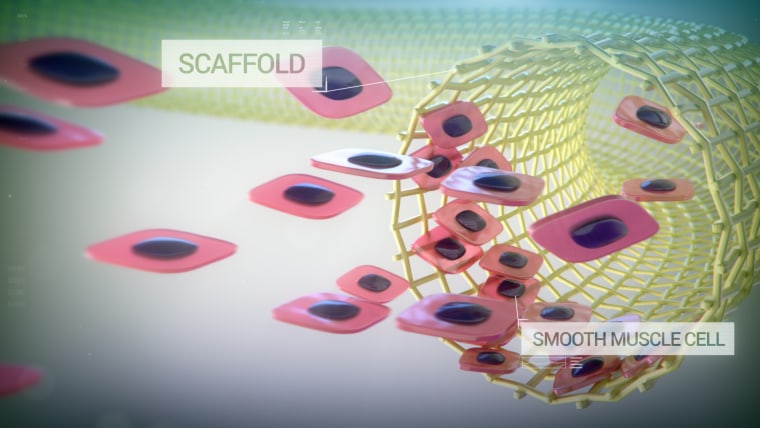

For the research, scientists and biomedical engineers at Yale University and Humacyte, a regenerative medical technology firm in Durham, North Carolina, created HAVs by taking arterial cells from cadavers, growing them into new vessels and then stripping out the cells. After the processing, all that remained was the so-called cellular matrix — the web of collagen and protein that gives a vessel its structure.

Then the HAVs were implanted in the arms of 60 kidney disease patients in Durham; Norfolk, Virginia; and three cities in Poland. The HAVs were used during thrice-weekly sessions of hemodialysis, the blood-cleansing treatment that takes over for ailing kidneys.

Hemodialysis is typically administered through a fistula, a surgical connection between an artery and a vein that is easy to access; or through a graft, which connects the two blood vessels through a synthetic tube. Both approaches have shortcomings: Not all patients are good candidates for fistulas, and grafts are prone to clots and infections.

The researchers followed the patients for three years after they received their implants. Whenever a participant went in for routine surgery to fix or maintain their implant, researchers harvested a tiny square of their artificial vessel. All told, the researchers obtained samples from 13 patients. Subsequent analysis of the samples showed that the prebuilt matrix was filled in with the patients’ own cells.

“Your own stem cells crawl into the spaces, realize that they’re in a blood vessel, and then differentiate into your own tissue,” Humacyte CEO Jeffrey Lawson said.

The analysis also showed evidence that the artificial vessels were able to heal themselves. In one sample, extracted about 10 months after implantation, new cells were seen growing around holes poked by needles during dialysis.

Eniola-Adefeso called the results promising but said there’s much to learn about how the vessels perform — including how well they hold up over the long term.

The scientists at Yale and Humacyte are looking ahead, too. Lawson said the artificial blood vessels could someday be kept on hand in hospital emergency rooms.

“This sci-fi notion of tissue engineering — we’re on the doorstep of doing it for real,” he said.

Want more stories about bioengineering?

- Lab-grown lungs successfully transplanted into pigs, raising hopes for human use

- These tiny robots could be disease-fighting machines inside the body

- Why tiny Neanderthal brains are now growing in petri dishes

SIGN UP FOR THE MACH NEWSLETTER AND FOLLOW NBC NEWS MACH ON TWITTER, FACEBOOK, AND INSTAGRAM.